Nestling among pleasant modern homes and flats in a leafy part of Stonehaven, stands the stump of an ancient chimney stack.

It’s easy to miss, tucked away in a quiet cul-de-sac, but the curious who take a closer look at the plaque which adorns the wall are often surprised to learn this old stonework is all that remains of the Glenury Royal Distillery.

To be more precise, the chimney base is the only physical remnant of this ghost distillery, mothballed exactly 35 years ago this Sunday.

Its spirit, however, is still very much alive in the whisky world.

Today, a bottle of Glenury Royal is one of the rarest, most sought-after and highly-prized finds for whisky aficionados around the globe – commanding prices from collectors that can run into thousands of pounds.

This Sunday, May 31, one of those bottles will be opened and enjoyed by Steve McQueen, owner of Stonehaven’s Fountainhall Wines. Albeit it will be just a miniature he managed to buy several years ago.

It is his way of commemorating a distillery with a rich and fascinating history, founded by one of the most colourful characters produced by the north-east, Captain Robert Barclay Allardice, famous in his day for walking 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours to win a 1,000 guinea wager.

“I will open that miniature and raise a dram to the distillery,” said Steve, who developed a fascination with Glenury after moving to Stonehaven some seven years ago.

“Glenury Royal is now a very rare and sought after whisky. I get a lot of people asking if you are able to get it and the answer is simply: ‘No I’m not’.”

Glenury was founded in 1825 just two years after the Excise Act of 1823, passed to stamp out illicit stills and whisky smuggling by allowing licensed distilleries to operate for a set fee and tax payments.

Barclay was quick to see an opportunity for himself and to help local barley farmers by setting up a distillery at Glenury, at a site reputedly once used by the moonshiners.

“Captain Barclay was obviously a very eccentric character,” said Steve, who admitted he had little whisky knowledge when he moved to Stonehaven.

“Initially I didn’t even know there had been a distillery in Stonehaven so it’s quite interesting to find out more and it’s quite sad that it’s gone.”

It wasn’t all plain sailing, as Captain Barclay’s fledgling business tried to find its feet.

Barely weeks after the distillery had opened it was hit by a devastating blaze.

In an announcement in the Aberdeen Journal, Barclay, Macdonald & Co, said: “A fire broke out in the malting premises, which has consumed the greater part of them, beside a considerable quantity of grain and malt. The distillery, however, and the whole distilling and brewing machinery and apparatus and stock of spirits have been saved.”

The run of bad luck continued, however, and in May 1825 a worker was fatally injured.

The Journal reported: “Andrew Clark, one of the workmen employed at Glenury Distillery, being sent to examine the state of the great boiler, by some unfortunate accident fell backwards into it and was so dreadfully burned, that he died in extreme agony at 7 o’clock in the evening.”

King William IV was

said to be fond of a dram

of Glenury whisky.”

However, Captain Barclay was undaunted and his distillery went from strength to strength. In 1835 he was allowed to add the Royal suffix to Glenury – one of only three distilleries ever to have that honour, the others being Lochnagar and Brackla.

The title reflected Barclay’s close friendship with the royal family and King William IV – said to be fond of a dram of Glenury whisky.

Captain Barclay died in 1854 and Glenury was taken over by William Ritchie & Co of Glasgow. After that, the distillery quietly continued to produce its whisky, the bulk of which went towards blending – including a King William IV blend.

It fell silent from 1929 to 1937 when it reopened as a state-of-the-art distillery, after investment in equipment meant it was capable of producing 3,000 gallons of whisky a week.

In 1953 it came under the wing of Scottish Malt Distillers and continued to be an important part of Stonehaven.

Steve said: “It was a good place for jobs and they even had their own maltings until the 60s or 70s, with their own malting floor. You don’t see that in many places these days.

“Back in the day it would have been old Joe out with his rake doing everything by hand.

“It’s a shame we don’t have that anymore.”

But in the 80s, the popularity of whisky had plummeted, there was a surplus of supply and a cull of distilleries was carried out – with Glenury Royal as one of the victims.

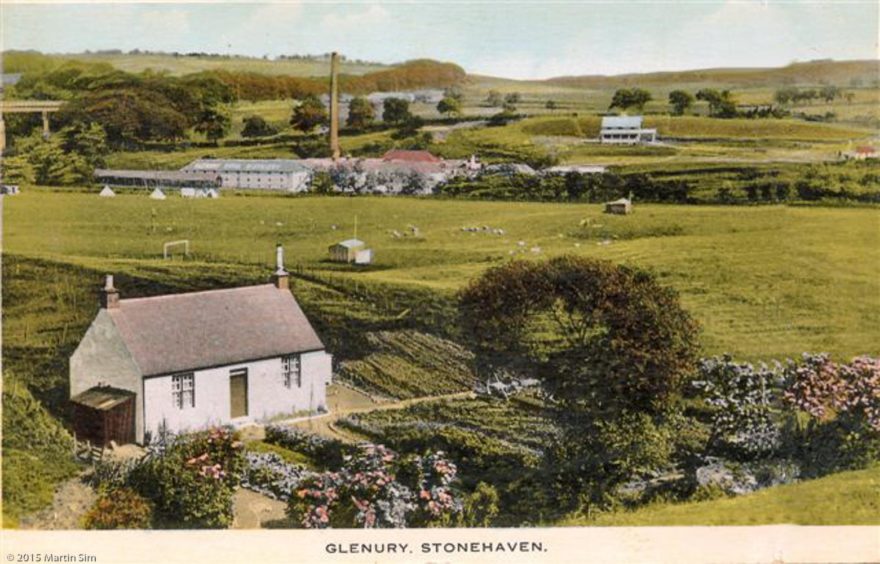

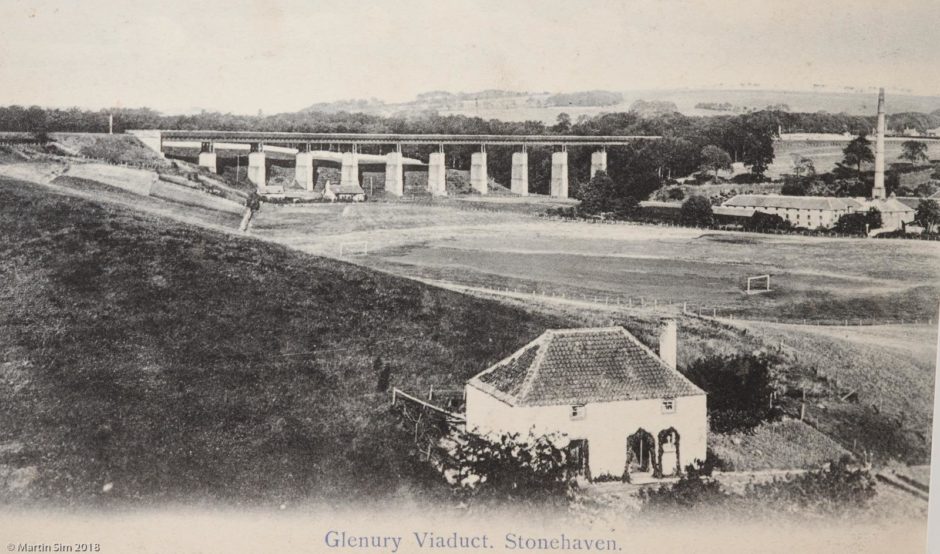

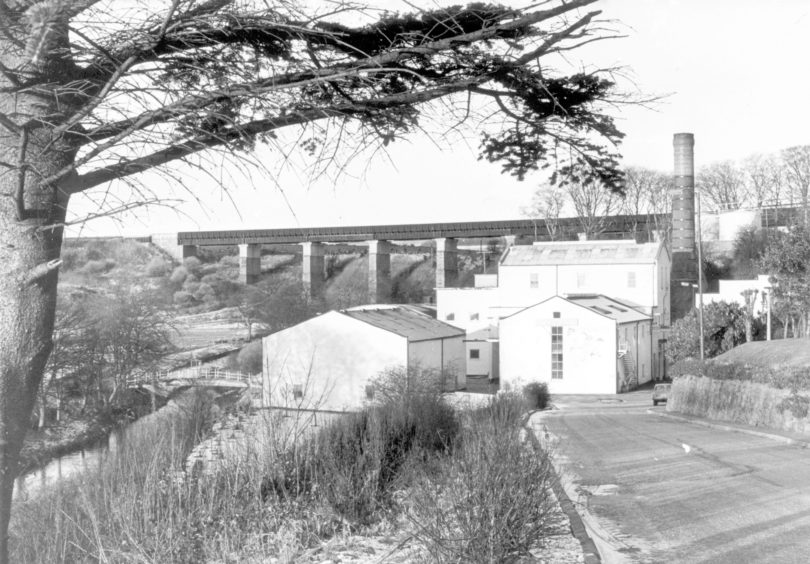

Empty and silent, local photographer Martin Sim captured many of the images you see here before the distillery was demolished.

Steve said: “For some distilleries the stock and buildings were kept then someone came along and opened them up again. Glenury wasn’t as lucky. The stocks were kept and moved about the place, but the distillery went.”

However, the great barrels where Glenury Royal was maturing survived. It has surfaced over the years in independent bottlings – including part of a Johnnie Walker Blue Label Ghost and Rare limited edition blend last year. But a bottle of single malt Glenury is hard to find.

Steve said: “Cards on the table… I’ve never tasted Glenury.”

However, he is looking forward to putting that right this Sunday, with a sample he spotted in a job lot of miniatures, snapped up in an auction for just £20.

“I like my Islay malts, my peated whisky and Glenury did use peated malt, so some of the characteristics will be lightly peated or a smokiness to it,” said Steve, adding his miniature is a 12-year-old from the 1970s.

“So on the 31st I will hopefully be pleasantly surprised by what the whisky is like.”

He had larger plans to honour the passing of Glenury – a unique tasting session of Glenury Royal whisky held in Stonehaven.

“I wanted to mark 35 years since it closed and had been buying in bottles for a wee while, sourcing them by pulling on the heartstrings of suppliers who still had some,” he said.

“I have about five bottles and the plan was to go to Cool Gourmet (on Stonehaven’s High Street), crack open these bottles and enjoy them and share some stories of the distillery.”

He still wants to share this rare dram with the people of Stonehaven, and plans to press ahead with his tasting session when the easing of lockdown allows.

“I think there will be a need for people to raise a dram to a few things,” he said, saying the bottles he has includes those by malt whisky specialist Gordon & McPhail.

There are some

50-year-old versions

out on the market

that can fetch thousands.”

“When the distillery was closing Gordon & McPhail very cleverly bought in a lot of its stock, so it’s a rare old collection.

“One example I have is from 1984, bottled in 2012,” said Steve, adding he also has the Johhnie Walker Ghost And Rare edition.

The scarcity of Glenury Royal pushes its price up above the £400 plus per bottle mark, with rarer versions fetching four-figure sums.

“There are some 50-year-old versions out on the market that can fetch thousands, a bit rich for my blood,” said Steve.

He reckons one bottle he was planning to breach could fetch £500 at auction.

“The salesman in me could sell the bottles, but that’s no fun. Whisky is designed to be drunk, so let’s crack these open and share them.”

Meanwhile, though, he knows many people in and around Stonehaven will have a bottle stashed away.

nb4UL1JV

For me, whisky

is designed

to be drunk.”

“Every month I get someone coming in and saying: ‘do you know how much this would be worth?’, because they’ve got a bottle tucked away in a loft or cupboard, but never opened.”

So, what would his advice be to someone with a bottle of Glenury?

“If you are planning on drinking it, then drink it. People have whisky collections and say they are saving it for a special occasion and it just sit and sits. For me, whisky is designed to be drunk.”

Meet the men who made the cratur…

Today Glenury Royal is a vanished distillery, but it still holds precious memories for the few left who worked there in its heyday.

For Jim Riddell, it was the place that launched a lifelong career in the whisky industry, seeing him work at distilleries across Scotland.

When I first started there in 1966

there was still a floor maltings

that was turned by hand.”

“When I first started there in 1966 there was still a floor maltings that was turned by hand,” said Jim, 80, referring to the traditional way of preparing barley for fermentation.

Jim, who is happily retired in Hopeman on the Moray Coast, worked stencilling casks and filling them at a time when Glenury Royal had its own cooper, rare even then.

“If somebody was ill or working on the boilers, then I was put on the mashing and just filling in. But I was still just a labourer really, and I wanted to get further on,” he said, adding he moved to Muir of Ord in 1968 to work as maltster.

“Glenury was a nice place to work. It was coal boilers in those days and a lot of stuff was manual. The mash tun had to cleaned out by hand twice a week.

“It had a good atmosphere and there were good people around me.”

Jim said the bulk of Glenury Royal went out for blending, with only a few private casks of the single malt.

“Single malt wasn’t really so popular then, it was all about blending in those days. It would have been going into Johnnie Walker and things like that.

When I retired they gave me a bottle of whisky from each distillery I had worked in, straight from the cask and

hand-bottled. The Glenury didn’t last long.”

“But it was a popular whisky and very good. When I retired they gave me a bottle of whisky from each distillery I had worked in, straight from the cask and hand-bottled.

“The Glenury didn’t last long, put it that way.”

Over his career Jim worked as a distiller and in management in distilleries including Glenlossie Distillery in Elgin, then Bladnoch in the south-west, and back to Keith to work in Aultmore Distillery while looking after Inchgower Distillery before he stepped down from the industry.

But he still has fond memories of the Stonehaven distillery that launched his career.

“There wasn’t a huge score of people, but they were all good, local guys. I was sad when it closed and there’s nothing left now, just a bit of the stack. I went down to see it and just thought: ‘My God, what a shame’.

“It’s just houses now.”

Stonehaven man George Knowles, now 81, was a young engineer at Glenury Royal.

“I was there for about eight years, finishing up in 1974,” he said. “I was the engineer so anything that broke down, I had to repair. I had a good job and for me it was a day shift job. But I was on call outside of that and if something broke down I had to come in and do what I could do with it.

George still reckons that was better than having to work on the three daily shifts many of his workmates faced as the distillery was a 24-hour operation.

There were a lot of

people who liked a

dram from time to

time, but I never did.”

“It was very important for Stonehaven at the time, but when they closed the place there were only a few people left working.”

Asked if he still has a bottle of Glenury Royal stashed away, George has a surprising answer.

“No. I never, ever had one. There were a lot of people who liked a dram from time to time, but I never did. I was on call most of the time, so I couldn’t very well get involved as much.”

The man who walked 500 miles… and then walked 500 more

Founding a distillery was just one of a remarkable string of achievements by Captain Robert Barclay Allardice.

Born on Ury Estate, just outside of Stonehaven in 1779, he was a national figure, famed for his feats of endurance and sporting exploits.

Barclay was known for his

remarkable strength.”

Most famously in 1801 he walked 1,000 miles in 1,000 hours to win a wager of 1,000 guineas. In doing so, he became a leading exponent of pedestrianism, a form of race walking that was popular in the early 19th century.

Barclay was also known for his remarkable strength – including a party trick of having a man stand on the palms of his hand before lifting him on to the top of a table.

He was a keen fan of prize-fighting, with his own stable of pugilists who he trained rigorously, earning large sums in wagers.

A keen gambler at Cambridge University he was part of a society, the Fancy, comprising fashionable, young men who made exorbitant bets on sporting events. One of his friends was the Duke of Clarence, later King William IV.

He once he drove

a coach from

London to Aberdeen.”

In later life, Barclay started his own stage coach service between Aberdeen and Edinburgh, often driving stages himself. He once he drove a coach from London to Aberdeen.

Captain Barclay also visited America, met President John Tyler and wrote a book about his exploits.

He died in 1854 after being kicked on the head by a horse.