It was a story which proved how art can thrive in a war zone.

And it began with a few paragraphs in a Scottish newspaper as the prelude to the establishment of a youth orchestra in one of the most dangerous parts of the world.

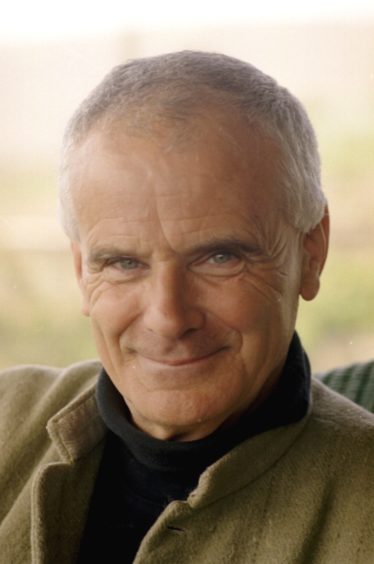

And, although a decade has passed since Paul MacAlindin embarked on his remarkable quest to nurture culture across Iraq, the myriad challenges he faced are indelibly imprinted in his memory.

Eating fish and chips

The Aberdeen-born musician and conductor freely admitted that the manner in which he set about founding the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq might have been dismissed as implausible if it had cropped up in a Hollywood film.

There he was, eating fish and chips in Edinburgh’s The Barony pub on a Sunday in 2008 when his eyes glanced at the headline: “Iraqi teen seeks Maestro”.

Straight away, MacAlindin’s curiosity was piqued and it sparked the beginning of a remarkable adventure, one which took him all over the globe.

He recalled: “I’m glad it said ‘maestro’, because if it had just said ‘conductor’, I would probably have turned the page and that would have been the end of it.

“But continuing to read, I understood that something potentially big might be happening.

“Zuhal Sultan, a 17-year-old pianist in Baghdad, was looking for somebody to help set up a youth orchestra in her homeland. And she was clearly very committed and determined to make it happen.

“At the outset, I had little knowledge of the scale of the task I was undertaking. Let’s get this into perspective. This was a country barely out of a terrible war, with no discernible orchestral tradition, so what could there be to work with?

“Who was playing music? What did it sound like? Who was teaching? What condition were the instruments in?

“And how could I and every other Westerner have been media bombarded with bloodshed and tragedy, but still be unknowing of who Iraqis really are?

“Fixated on the article, with fish trembling on the end of my fork, I simply told myself inwardly: ‘I know how to do this’.

The spark had been ignited but, as he has explained in his book Upbeat, there was plenty of red tape and other travails for MacAlindin as he embarked on the venture.

He contacted Paul Parkinson at the British Council in London and subsequently arranged a meeting, via Skype, with Zuhal, who immediately impressed him – “Sometimes I had the feeling she was the 40-year-old and I was the teenage girl” – and spoke to his close friend, Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, at the time the Master of the Queen’s Music.

Barely able to speak the words

Bit by bit, the pieces came together, not least through the commitment displayed by Davies, who died in 2016.

As MacAlindin recalled: “During my phone call with Max in his Orkney home, I managed to declare myself the ‘Musical Director of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq’, barely able to speak the words.

“He replied: ‘All my love goes out to you’, then he blurted out: ‘And I will be your Honorary Composer-in-Residence’.

“Max had marched in London, along with so many other British people, against the Blair government’s war in Iraq.

“He was genuinely passionate about what had happened and became our first big-name supporter. For my fledgling team, his public acceptance alone boosted morale significantly. Moreover, his approval told me that what I was doing was right.”

The next few months passed in a giddy whirl for him and his callow proteges on the other side of the world. In 2009, despite all manner of logistical complexities and financial hiccups, they ran their first summer school and the orchestra was coming together by 2010.

Within a few years, this group of young instrumentalists came through the most difficult and dangerous of times to produce fine music, not only in Iraq, but also Britain, Germany and France.

Risking their lives

MacAlindin pulled together a diverse ensemble of both Arabs and Kurds – not natural colleagues – who were largely self-taught and had suffered immensely in the war.

They were also risking their lives because the so-called Islamic State regarded the creation of the NYOI as anathema. Hence the need for courage and persistence from everybody involved in the venture.

MacAlindin added: “It was a hard job to spread the word at the start. All the media coverage about Iraq tended to focus on war and conflict and it was difficult to get the message across that positive things were happening.

“I haven’t tried to sugar-coat the orchestra’s story. It triggered a lot of anger among some Iraqis, who felt we were involved in a propaganda exercise.

“I explained to them, factually, without embellishment, that art could have a positive influence and we were working to take young people out of a dangerous environment, but not everybody believed us. I can say categorically that we had no political agenda, but you can only do your best.

“There were successes and it was incredibly uplifting to watch these musicians come together and do it with a sense of joy. But there were constant reminders of how terrorism was spinning out of control.

“Koki, a young musician in Baghdad, was killed by a car bomb outside his home. His innocent face appeared again and again in tributes from our players.

“Du’aa Al Azzawi missed her exams, terrified of leaving her front door. Hussam, our principal cellist, posted a picture on Facebook of a 10-year-old boy he was teaching with a cello that was too big for him.

“It was hard being in the midst of all this and seeing musicians trying to hang on to their humanity, amid increasing despair and hopelessness, watching violence and corruption drain their futures away.

“And yet, the love, commitment and respect they showed me in Iraq became core values for us all to live up to when we performed at the Edinburgh Festival or Beethovenfest.

“They demonstrated wholeheartedly that they wanted to work together with discipline, good communication, transparency, better teaching, listening and learning while bringing the whole of Iraq together.

“From a bunch of young adults who had thrown themselves into this unique project on a wing and a prayer, they were fresh, dynamic and highly articulate. Knowing a little of where they came from, they were decisively stepping away from their status quo.”

Julian Lloyd Webber was among those who saluted MacAlindin’s ebullience and enthusiasm, while declaring the NYOI’s success around the world was proof of how music had the power to create harmony out of chaos.

But, behind the scenes, there was an incessant struggle to surmount the obstacles generated by the rising tide of ISIS atrocities and corruption inside Iraq itself.

A proposed tour of America was eventually stymied by repeated objections from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services.

As MacAlindin explained: “The crux of their paranoia lay in the fact our orchestra’s membership was not constant and we performed only once a year.

“So, in their minds, a potential terrorist could have been added to the list (of band members) by pretending to be a violinist.

“I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Anybody who had bought into such extremist ideologies would have either given music up or been executed by his comrades for playing a violin long ago.

“They were also concerned that some players would enter and not leave, though this was an issue for the State Department in Baghdad, not them.”

Reasons for optimism

It was a frustrating stalemate, but there were many other reasons for optimism. Zuhal Sultan moved to Scotland and studied law and politics at Glasgow University.

She and many of her orchestral companions found expression and enlightenment through music. Sir Peter Maxwell Davies donated a seven-minute piece, Reel of Spindrift, Sky, which straddled the divide between Iraq and Orkney.

As he stated before his death: “The great adventure of the NYOI serves as an example of how the essential can survive catastrophe.”

As for MacAlindin, all the political imbroglios and bureaucracy failed to diminish his passion for the enterprise and especially as he watched shy, scared teenagers become confident young adults.

He said: “It opened up a whole new world to everyone and they grew stronger for themselves and Iraq. The impact on the NYOI’s women cannot be underestimated.

“Everybody played their role as cultural diplomats brilliantly and won over thousands of hearts and minds through the supporting youth orchestras, performances and the international media.

“Determined to bring isolation to an end, the players forged international friendships and learnt to communicate not just with one another, but with the music world.

“Inevitably, a handful grew beyond all expectations to create a new vision for themselves and others, who will carry the NYOI’s energy forward in the future in new ways. It was an enormous pleasure and privilege to work with them.”

MacAlindin has dedicated his book to “the brave young musicians of Iraq”.

He, too, has demonstrated resilience and resolve on his gruelling journey.

Upbeat is published by Sandstone Press.