They were the forgotten victims of the Second World War – from all across the north of Scotland – who suffered in their thousands.

It will be 80 years on Friday since the surrender of the 51st (Highland) Division, who experienced horrific loss of life in the aftermath of the Dunkirk evacuation in France.

Time’s passing hasn’t diminished the scale of the disaster, nor lessened the grief felt by the families of the thousands of men who were killed or forced into a gruelling march from St Valery-en-Caux to prisoner of war camps.

Around 10,000 survivors, from The Black Watch and the Queen’s Own Cameron, Seaforth and Gordon Highlanders, were captured during the hostilities and spent the remainder of the conflict as prisoners, often enduring appalling hardship.

On June 12 1940, just days after the successful mass evacuations at Dunkirk, thousands of British troops remained on continental Europe under French command.

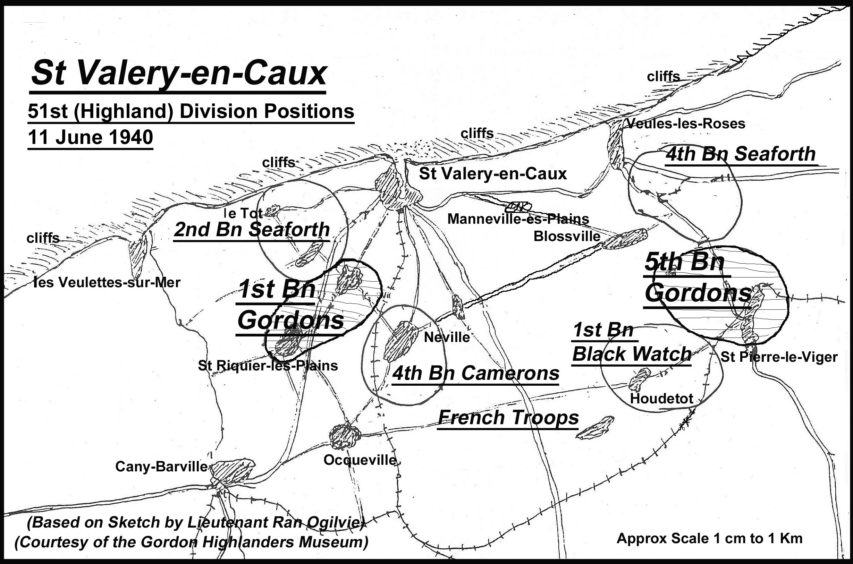

Largely comprised of men from the 51st (Highland) Division, they fought almost continuously for 10 days against overwhelming odds until they were eventually surrounded at St Valery.

Plans were devised to extricate the soldiers and orchestrate an escape route. But a combination of fog and the proximity of German artillery above the town prevented the awaiting flotilla of ships from reaching shore, and the men who had been clinging to the hope of being rescued gradually realised the “cavalry” wasn’t coming.

Brigadier Charles Grant, a retired British Army officer and historian of the 51st (Highland) Division, said: “The division – initially about 20,000 strong – comprised nine battalions of the Highland infantry regiments with supporting arms and services, including elements from England.

“They had been detached from the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and therefore managed to escape encirclement around Dunkirk.

“Instead, from June 4, they were conducting a fighting withdrawal west from the Somme under French command.

“However, the speed of the German advance was such that they, and part of the French army, were cut off, despite hopes that they would escape through Le Havre.

“Part of the division did get to Le Havre to secure it for evacuation and escaped, but the remainder were cut off and surrounded at the little fishing town of St-Valery-en-Caux.

“Not unlike Dunkirk, a flotilla of 67 merchant ships and 140 small vessels were organised and then despatched from several British ports, but the inclement weather and the German artillery who were overlooking the town meant that any evacuation on the night of June 11 was impossible.

“General Victor Fortune, who was commanding what remained of the Division, considered all the options – a counter-attack, further resistance or retaking the town. But, against this, there was no possibility of evacuation or support.

“The men had been fighting almost continuously for 10 days against overwhelming odds. They were exhausted and virtually out of ammunition, with no artillery ammunition left at all. Shortly before 10.00hrs on June 12, General Fortune took the most difficult of decisions – to surrender.

“There can hardly have been a town, village or hamlet in the Highlands and beyond which was not directly affected by the loss.

“While events such as Dunkirk, D-Day and VE Day are rightly commemorated, it is time that the memory of those who fought and fell at St Valery is remembered in a national tribute for the first time.”

Stewart Mitchell, a volunteer researcher at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, has investigated the campaign and written a book about it.

He told the Press and Journal: “The country recently commemorated the 75th anniversary of VE Day, which marked the end of the Second World War in Europe.

“Among those celebrating the outcome in 1945 were thousands of newly liberated men who had spent five long years as POWs, forced to support the Nazi war effort doing hard labour in mines, quarries, factories and farms in Germany and Poland.

“Many were captured at St Valery in the worst military disaster affecting Scotland during the war. Despite its significance, there are many myths surrounding the surrender of the 51st (Highland) Division.

“At the museum, I often hear (from visitors) that a relative was captured when the Highland regiments were sacrificed by Winston Churchill ordering them to defend the Dunkirk perimeter so that others could be evacuated.

“This belief developed because the need to maintain public morale had turned the disaster of the rout of the British Expeditionary Force into ‘the miracle of Dunkirk’. The bad news of the surrender of the 51st (Highland) Division, just 10 days after the last ships sailed from Dunkirk, was airbrushed from history.

“This was compounded by the reluctance of the men involved to speak about their experiences. Even now, relatives of these brave troops often remark, ‘He never spoke about it’ after returning home, so the myth went unchallenged and became accepted.”

In the defence of St Valery, many courageous acts took place as the desperate Scottish soldiers did their utmost to respond to what was a grievous situation.

2nd Lieutenant Brian Hay, the son of Lord Hay of Seaton in Aberdeen, was commanding a defensive position when two Germans issued a surrender demand.

Lt Hay, who had no thought of accepting such an ultimatum, refused and finished his exchange with the enemy by affirming: “Take that back to your general”.

The tidal harbour limited the large ships berthing and the evacuation of thousands of soldiers was difficult, compounded by the high chalk cliffs, on either side of the town, which restricted access to the shore.

There was still hope they could be retrieved, but Sergeant Alex Moir, from Stuartfield, feared this was an increasingly slender prospect. A group of men strove to get to the beach, but discovered the 300ft sheer cliffs stretched as far as the eye could see.

In despair, they tied their rifle slings together to lower themselves down the cliff, but gave up when one of their number, Malcolm Mackintosh, fell to his death.

Meanwhile, the fighting continued across the area and heavy casualties were suffered, as evidenced by the number of Scottish names in the war cemetery in St Valery.

James Reynolds, from Aberdeen, was among those serving with the 5th Battalion Gordon Highlanders when he was killed in action at Blosseville, just outside St Valery.

He was buried by his comrades but his grave was lost in the mists of time and, tragically, he now has no known resting place. He was not alone.

By the morning of June 12 it was clear to General Fortune that the situation was hopeless. Heavy rain and fog had prevented the Royal Navy and the other boats from reaching the harbour the previous night and, with the Germans assembled in force on the cliffs above the town, they could not approach the shore in daylight.

He eventually, reluctantly, surrendered to General Erwin Rommel, who subsequently became better known for his role in the North African campaign.

The men were ordered to lay down their arms and were marched off into captivity.

Sergeant Charlie Fullerton, from Balmedie, slipped through enemy lines and got to the pier by daybreak, but found it was being raked by enemy machine-gun fire.

Undaunted, he took two men with Bren guns and returned to the beach, only to be confronted by a tableau of utter chaos with soldiers lying dead and dying.

Along the beach they saw two ships, one beached and the other lying only some 300 yards offshore.

There were glimmers of hope, but their efforts to reach the vessels attracted the attention of a German machine-gun post and, under a hail of bullets, they ran to the beached vessel and climbed on board to find it full of wounded soldiers.

The Germans fired armour-piercing shells and threw grenades down the cliff, so Sgt Fullerton and Corporal Bill Grant swam to the shore where a group of Germans were waiting for them with machine-guns.

The latter allowed the Scots to put on their boots and marched them off to the top of the cliffs. On the way through the town, where the lower part and seafront was in ruins with burning buildings all around, they passed General Fortune.

Sgt Fullerton gave the “eyes right” command as the party passed him to show that, despite being forced to surrender to the enemy’s superior numbers and equipment, they were not disheartened.

Mr Mitchell said: “Heroically, a number of men escaped shortly afterwards, slipping unnoticed from the huge columns which were marching through northern France.

“One of these was Alex Moir, who successfully made it back to Britain and rejoined the Gordons who were fighting in North Africa. Yet tragically, he was killed in action in November 1942 during the Battle of El Alamein.

“Charlie Fullerton also escaped and managed to return home where he was awarded a Military Medal and promoted to the rank of lieutenant.

“Another successful escapee was Corporal Malcolm Straughan who, by a twist of fate, was a member of the reformed 51st Highland Division, which liberated St Valery-en-Caux in September 1944.”

Most of the casualties of this grim chapter of the war are buried in cemeteries in and around St Valery.

There were so many deaths that few communities in the north of Scotland were unaffected.

Almost none of the veterans of the battle are still alive to mark its 80th anniversary. And the postponement of the commemorations in France, due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, means it is unlikely that any of the old campaigners will have the opportunity to attend a future anniversary to mark that fateful day in history.

But they deserve to be remembered for their selfless sacrifice in the Allied cause.

Further details can be found in St Valery And Its Aftermath, written by Stewart Mitchell, published by Pen & Sword Books.