She was the north-east nurse who cared for wounded soldiers throughout the First World War and dealt with the Spanish Flu pandemic which followed the conflict.

And although Henrietta Tayler was, in her own words, “five foot nothing”, she packed a lot into her incident-packed life, which included treating stricken military personnel during the 1918-19 outbreak of the deadly disease when medical staff wore “eucalyptus masks” to protect themselves.

Blazed a trail

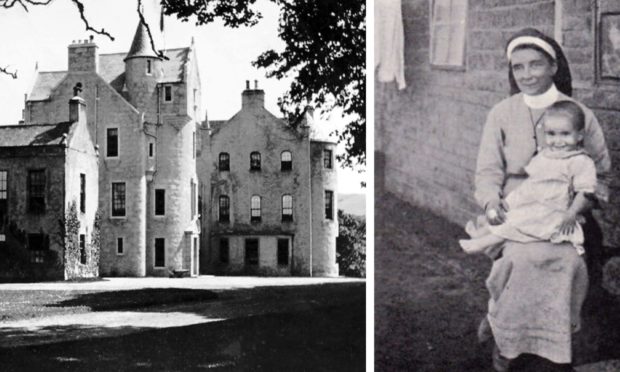

A new book by Huntly-based writer, Maggie Craig, has revealed how Miss Tayler blazed her singular own trail, whether at home in Scotland or across Europe, after spending her summers at Rothiemay House in Aberdeenshire.

She subsequently became a far-travelled nurse who witnessed myriad horrors during the Great War, but wrote powerfully about her determination to do whatever she could to help other people and especially the many youngsters on the front line.

Born into the Scottish gentry in 1869, she devoted herself to scholarship – and was acclaimed as an expert in Jacobite history – while she and her brother, Alistair, published more than 30 full-length books and had a special interest in the Duff family to which they belonged, and which also includes the poet Lord Byron.

Yet, when the war broke out in 1914 – by which time Miss Tayler was in her mid-40s – she embarked on a new and dangerous challenge which severely tested her mettle.

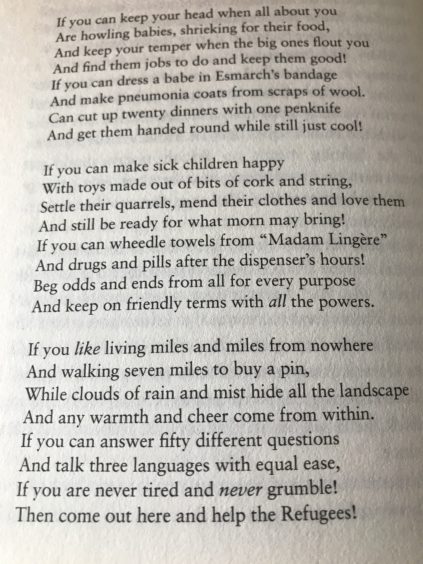

Miss Tayler served throughout the conflict as a Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse, putting herself in danger to help wounded soldiers on both sides as well as refugee children, who had lost their families.

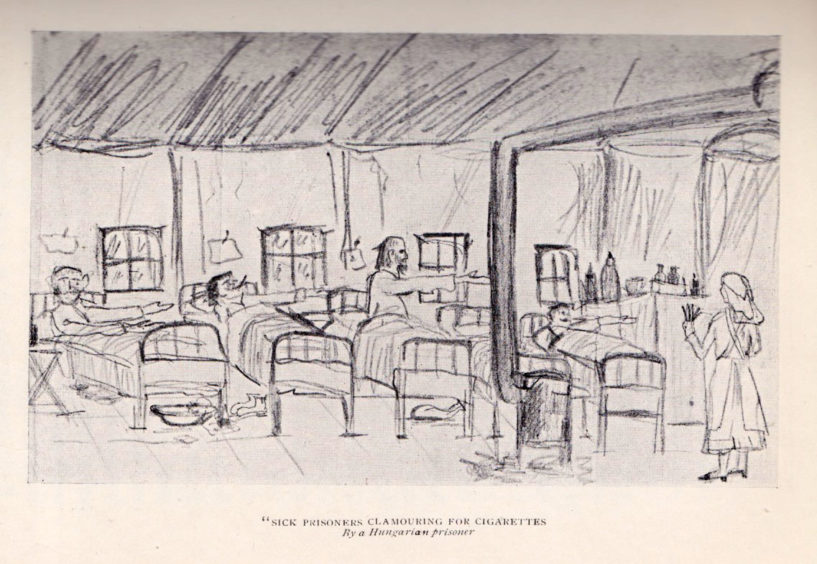

It was often a harrowing life and she later admitted there were many heartbreaking incidents where she had to watch young people dying in front of her.

But, as Mrs Craig said: “She carried out her work as she did everything – with bravery, wisdom and good humour.”

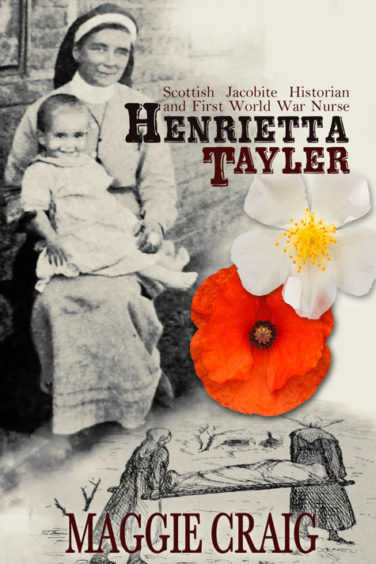

And this included her own alternative version of the famous Rudyard Kiping poem If.

The author added: “I first came across Hetty when I started seriously researching Jacobites 25 years and longer ago.

“Trying to get back to primary sources wherever possible, I looked at the bibliographies of other books and kept finding references to books by A&H Tayler.

“Hetty always put her beloved brother first, although some things I have read imply that she was the intellectual powerhouse. When I first read their books in the Special Collections at Aberdeen University, I often felt like laughing out loud at some of her more acerbic comments and footnotes.

“She was a character, all right. I then read her memoir of the First World War (at Aberdeenshire Libraries at Oldmeldrum) and she leapt off the page, brave, capable and with a great sense of humour, even in the grimmest of situations.

“So my biography of her is a wee tribute to an amazing woman.”

Helen Agnes Henrietta Tayler was born in London in 1869 but always considered herself to be a Scot.

Every summer, they travelled north to spend the summer at William Tayler’s childhood home of Rothiemay House, near Huntly in Aberdeenshire.

There were three children; Constance, Hetty (as family and friends always called her) and younger brother Alistair.

In Banffshire, William Tayler was known as the Laird of Glenbarry, a title his son would later inherit.

There were frequent visits to Duff House in Banff, the beautiful William Adam-designed mansion at the mouth of the River Deveron.

Artefacts galore

William Tayler had been born there, the grandson of the 3rd Earl Fife.

Supremely ‘weel-connecktit’, Miss Tayler and her siblings came to know many lairds’ houses across Banffshire and Aberdeenshire.

This was living history, with charter rooms bulging with documents and houses full of paintings and artefacts galore.

Their imaginations fired, Miss Tayler and Alistair forged a life-long research and literary partnership and worked for decades together.

Their first published work was a two-volume history of their own family and its many branches.

The Book of the Duffs was published in 1914.

However, when the war broke out later that year, she needed no invitation to commit herself to the world of nursing.

As a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), she helped to look after Belgian refugees fleeing from their war-devastated country and the invading German army.

Returning to Banffshire, she subsequently became matron of a VAD hospital for wounded servicemen at Earlsmount, a large house in the town of Keith and was known for her mixture of compassion and steely-eyed diligence and duty of care for those who needed medical assistance or even a shoulder on which to cry.

Mrs Craig added: “Eager to serve abroad, she then went to care for Belgian children in the small part of their country which was still under Belgian control.

“With the pounding of the guns on the Western Front shredding everyone’s nerves and terrifying her young charges, Hetty was a soothing presence.

“Her philosophy of life could be summed up by the famous Second World War slogan: ‘Keep calm and carry on’; do whatever you can to help and look for something to laugh at wherever you can find it.

“She was a short woman, barely five feet tall, but she had a big heart, an inquiring mind, a great sense of humour and a ready smile.”

There were many cases, as the hostilities raged on, where every shred of her fortitude was required to cope with the strains of tending to the sick and seriously wounded.

Tens of millions

Throughout the course of the war, she nursed and cared for soldiers and civilians in some of the most perilous corners of Europe and was renowned for her unflappability.

Yet even she was shocked at the fashion in which so many apparently strong young men succumbed to the Spanish Flu, which killed tens of millions of people.

Mrs Craig said: “In Italy, she nursed servicemen who were suffering from influenza during the global pandemic of 1918–19.

“She wrote in a short memoir, A Scottish Nurse at Work: ‘We did all our work in eucalyptus masks and everything was disinfected, even our letters’.

“Twelve men died during the first two days after Hetty’s return to Italy, as well as one of the doctors. But nurses and doctors were so busy looking after the patients that the state and cleanliness of the wards had to be left to deteriorate.

“Hetty wrote that what was really heartbreaking was the sight of ‘strong young men, poisoned through and through, burnt up with fever, fighting for their lives and passing through delirium and coma to the final collapse’.”

Even her phlegmatic temperament was rattled by the horror of it all.

Miss Tayler put her language skills to good use after the war, when she and her brother carried out research on the House of Stuart in archives in Paris and the Vatican.

In 1934, they started looking through the Stuart Papers at Windsor Castle. These had been bought on behalf of George IV even before the death of Charles Edward Stuart’s brother Henry, who was a cardinal of the Roman Catholic church.

The letters and papers were bound into over 500 volumes and were not then indexed.

But, undaunted, Miss Tayler and Alistair were, she wrote, proud to have been the last historians ‘to sail the uncharted seas of the Stuart Papers, making on the way the most thrilling discoveries’.

They did all this in the days before photocopying, when everything had to be painstakingly transcribed by hand.

Henrietta Tayler never married nor had children, but she was honorary auntie to many members in her extended family and created friendships wherever she travelled.

Alistair died in 1937 and, devastated though she was by the loss, she kept writing with the resilience and tenacity which defined her while life.

Fatal shooting

Mrs Craig said: “Hetty died in April 1951 at the age of 82, shortly after completing an article for the Scottish Historical Review on the accidental fatal shooting of Angus MacDonell by his own side in Falkirk after the battle there in January 1746.

“Hetty was buried beside her mother and brother in the Brompton Cemetery in Kensington in London.

“The Taylers’ meticulous scholarship and Hetty’s ability to put the information across in a lively and entertaining manner forms a huge amount of what we know about the Jacobites of 1745.

“In so many different ways, she was a remarkable woman.”

Further information about the book is available at www.maggiecraig.co.uk