There was great excitement in Aberdeen as the stunning new bells for the spire of the Mither Kirk were paraded through the streets for citizens to admire, before ringing out in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee.

Come the big day in 1887, the 36-strong carillon was in place at St Nicholas Kirk, the Granite City was ready for a celebratory sound such as never heard before and then there came… silence.

“If you were stood right by the bells you could hear them, but they just didn’t work,” said Dr Arthur Winfield, project leader for the Mither Kirk Project, a planned £5 million redevelopment to transform part of the church into a community space and visitor centre celebrating Aberdeen.

A problem with the casting meant the bells were barely audible and for many of them the tuning was off. It was to be another 65 years before the carillon of St Nicholas was heard – but only after being completely recast in 1952.

The silence of the bells is just one fascinating story in the more than 800-year history of the medieval Mither Kirk.

It has survived through the Reformation, neglect, fire – and even dark periods when it was used to jail suspected witches before they were burnt at the stake.

Today the Mither Kirk is back in the news, with proposals to end regular worship in St Nicholas forming part of a review of the Church Of Scotland estate in Aberdeen.

A decision is due in October.

A church at the heart of the city

Despite the possible end to regular worship, the church is at the very heart of the city, its history, traditions – and hopefully its future, according to Dr Winfield.

However, its actual origins are lost in the mists of time. No one is even sure exactly when it was founded.

“Exactly is the operative word. We have no idea. There is one bit of the building which looks as though it dates to 1100 or earlier. But the first written reference is 1157 in a Papal Bull,” said Dr Winfield.

Way back then it was

the Mother Church

for the city of Aberdeen.”

While formally named for St Nicholas, the term Mither Kirk goes back to its earliest days, he said.

“It was a medieval term, the mother church, and way back then it was the church, the Mother Church for the city of Aberdeen.”

Unusually for the time, the church was built on the edge of the existing town almost outside its gates – the Castlegate, Gallowgate and Upper Kirkgate – which ran down towards the harbour area

“It was more or less fields westward, yet the kirk was built in that position, which is odd,” said Dr Winfield. “Normally a church would be in the centre of the community. We don’t really know why, but we speculate that because at that time it was on a promontory.

“It’s not obvious as you look at the city now, but it was actually built on a hill,” he said, saying natural features, such as burns and lochs have been built over and vanished across the centuries.

A glimpse into the past

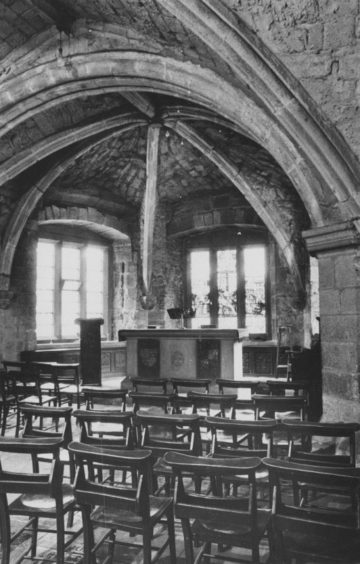

While no one knows what the first St Nicholas looked like there is still a clear trace of the earliest kirk, uncovered in an archaeological dig in 2006.

“It’s an apse of that very first building and we think it is about 1100, it could be a bit earlier. It’s the oldest visible wall in Aberdeen. It’s inside the church, there is a viewing window into where the archaeology used be and if you look down you can see part of that apse… but you have to know to do that.”

As the city grew, so did the Mither Kirk. With more trade and industry coming to Aberdeen, St Nicholas became a hub for commerce as well as worship.

“If you shook hands on a deal in a church, it was far more binding than if you did it anywhere else. So on a regular basis it was just thronged with people throughout the week,” said Dr Winfield.

And more rich merchants meant more men of influence looking for their place in eternity, to the church’s benefit.

“Any wealthy people when they died, tended to endow an altar and pay the wages of clergy to say prayers for them and their family,” said Dr Winfield.

“By the early 1400s there were more than 30 different altars, so it was far too crowded and had to be expanded,” said Dr Winfield.

Special taxes were put on the harbour to pay for the building work, which took more than a century to complete.

That was the origin of St Mary’s Chapel, built at that time as a separate building until gradual expansion encompassed it into the body of the kirk – but not diminishing its intriguing and at times unsettling past.

“It was originally used by a group of ladies called the Order of St Mary of the Pity and their focus of devotion was the suffering of Mary at the time of Crucifixion, so that’s what it was steeped in.”

A witches’ ring…

After the Reformation, St Mary’s was deemed too small to use for worship and was instead turned to other uses.

“There is still in St Mary’s Chapel

the ‘witches’ ring’ built into the wall

which they shackled them to.”

“It is one of the more infamous parts in the kirk’s history that the building had two prisons within it. One of them was in the old wooden spire, the other was St Mary’s Chapel. It was used to hold the witches when the witches’ trials were going in the late 1590s,” said Dr Winfield.

“There is still in St Mary’s Chapel, the ‘witches’ ring’ built into the wall, which they shackled them to. I was sceptical about that and thought it was just a bit of metal, but when the city archivist commented on it he said they still had the invoice from the contractor for putting that ring in. It is fascinating.”

The chapel was also used to store the city’s gallows at one point and it has been a soup kitchen. Latterly it was the FairTrade shop for Aberdeen.

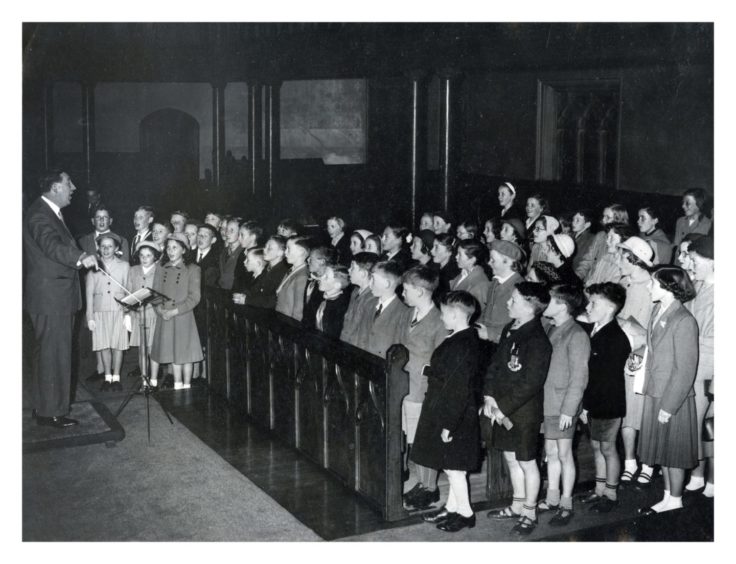

In sharp contrast to some of its dark times, St Nicholas was also a place of music, said Dr Winfield.

“It was quite early in having an organ. The city records show there was an organist in 1437, paid 26 shillings and eight pence a year,” he said, adding the instrument was ordered demolished after the Reformation.

“They had a ‘sang school’, a choir school, that was quite famous in the 1600s when a lot of church music, unaccompanied, was being composed there. But the entire choir got sacked once for misbehaviour, except one elderly gentleman. They were just chattering during a service I think.”

And then there were the bells… but there was silver lining to the misfiring Victorian carillon.

“It was 1952 when they decided to get them recast with the correct metal. There were 37 bells at that stage which were recast and they worked perfectly. It worked so well they added more bells in 1957 to take it up to the present 48. So it is now the biggest carillon in the UK.”

At the Reformation, the kirk was divided into two sanctuaries, east and west. The East Kirk was still used, but the West Kirk fell into disrepair and in 1732 it was deemed unsafe.

“The present West Kirk was built in the 1750s and was designed by an Aberdeen architect, James Gibbs, who was given the freedom of the city, so this was his gift back to the city,” said Dr Winfield.

“His most famous church is St Martin-In-The-Fields in London and there are quite a number of similarities in detail. You can tell it was the same architect.”

Demolition — and a replacement

In the 1830s, the then minister decided the East Kirk was old-fashioned and had it demolished, replacing it with the present building.

“So what you see today was more or less settled by the 1840s, except it still had a wooden spire. But there was a fire in 1874 that burnt it down. The present stone spire dates from 1878.”

Today, the Mither Kirk Project is dedicated to creating a new and vital space in the east side of the A-listed building. It was during this work in 2006 that the medieval wall was found – along with something both gruesome, yet touching.

The archaeological dig, necessitated by creating a new foundation, unearthed thousands of skeletons.

Dr Winfield said: “Each time the church expanded it was over the kirkyard. So the dig uncovered parts of just over 2,000 people and 900 complete people. It is a huge number to comprehend. They were really packed in tight, side-by-side, layer upon layer.

“There were all sorts of artefacts, bits of jewellery, pottery – they found a pair of glasses. On the chest of one was a little heart-shaped brooch with an arrow through it, a love token. So you got all sorts of touching things like that.”

These souls, with one skeleton of a baby dating to the 1100s, will be re-interred in a new crypt being created at the dig site. It will be part of the Mither Kirk Project, which will create a visitor centre to showcase the development of Aberdeen and possibly house the city’s ancient archives.

Project will come at a cost

Dr Winfield said the current work is in preparation for the completion of the new centre – providing funding can be found for the £5 million cost.

“That is obviously a lot of money. But I see it as an opportunity for people who may be able to help, to help Aberdeen come out of the current lockdown and do some serious work to revitalise that part of the city centre.”

Dr Winfield said the Mither Kirk has a unique place in the heart of the city and in the heart of the people of Aberdeen, which is why it has survived more than eight centuries with its “mother church” role.

“Right from the start it has been the civic church. It’s where the Kirkin’ of the Council goes, it gets used for big events such as the memorial services after the Piper Alpha disaster and the Super Puma helicopter tragedy.

“It is obviously used on Remembrance Sunday every year as well.

“It was the church of the city and still is. Could you imagine the city centre without that building there?”