It’s a song which defined a generation and rallied people who were flung into one of the worst situations they had ever known.

The lyrics evoked a sense of hope, of old acquaintances being renewed in some uncertain future, at a time when the world was engulfed in lethal conflict.

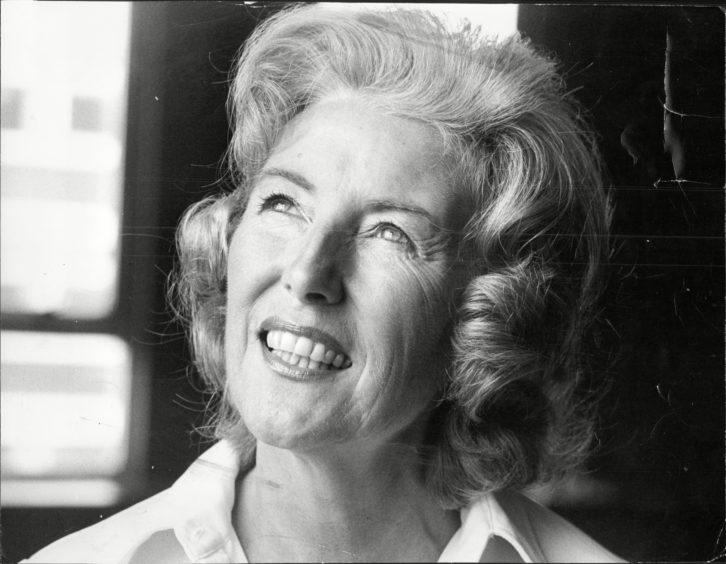

So it’s hardly surprising that We’ll Meet Again remains one of the most poignant melodies from the Second World War and survived the transition from the 1940s into the 21st century as new generations took heed of its message.

This was no tub-thumping anthem, as performed by Vera Lynn, from the song written by Ross Parker and Hugh Charles.

On the contrary, it was the wistful nature of the words – “Don’t know where, don’t know when” – which summed up the feelings of millions of families as they were torn apart and their lives were inextricably changed.

It spoke to those who watched, through moist eyes, the sight of their young children being evacuated from the big cities in their hundreds of thousands – and to the wee souls who waited years to be reunited with their parents.

Or, in many cases, parent.

It spoke to those whose husbands or sons, cousins or uncles, brothers or nephews were enlisted in the battle against Germany as the home fires only just kept burning.

And it speaks volumes for its continuing influence that even on the 75th anniversary of VE Day last month – and in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic – there was one song which straddled the divide and one singer capable of uniting people aged nine to 90.

My own memories of the impact of We’ll Meet Again won’t be that untypical.

Growing up in the 1960s, my mother, Agnes, had been just six years old at the outbreak of war and she and many of her friends never forgot how it affected the adults in their midst, nor of how they grew up in an atmosphere of trepidation.

My father, David, signed up in 1941 at the age of 18 and was subsequently involved in some of the most intense fighting of the conflict at Monte Cassino in Italy, a place where thousands died and others returned with memories they could never shake off.

When they were married in the late 1950s in West Lothian, the music at their wedding reflected their diverse tastes.

There was a Robert Burns song – my mum had a beautiful soprano voice and performed with the famous Orpheus Choir – and an excerpt from Handel’s Messiah, followed by the Glenn Miller standard In the Mood.

But there was also another refrain which tugged at the heartstrings of the older members of the wedding party.

Yes, We’ll Meet Again was still a song which harked back to so many lost boys and girls and not just from the 1940s.

My grandfather, David, had been involved in the fighting during the First World War and he devoted the rest of his existence to helping people, whether with the Co-operative movement or as a councillor, and after he became provost of Whitburn.

He related one painful memory about catching a young woman stealing milk from the back of his lorry.

As he said: “She was just a lass of 19 or 20.

“She had nothing.

“She had lost her dad in the war.

“Didn’t know where her mum was.

“Her bairn was three months old.

“He kept crying.

“What else could I do?

“The lass needed milk for the wee one.

“(She was) really greeting by the end.

“I looked at her and I felt very guilty.

“So I gave her the milk.

“And she looked so happy.

“But how had it come to this?”

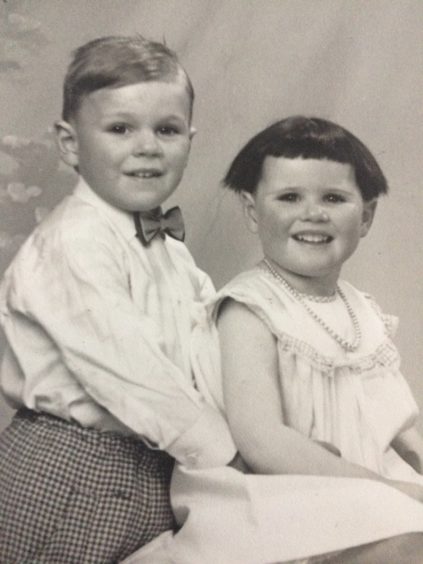

He died in 1969, but he talked to my sister Jean and me about his personal history and his words reflected the sacrifices which were made by his generation.

He wasn’t a jingoistic fellow – quite the opposite – but he realised there were some conflicts which had to be won, especially after his own experiences in the trenches.

Just a few hours before Armistice Day was officially declared in November 1918, his best friend Alistair Clarkson was one of the last victims of the slaughter in Belgium.

It had haunted him at the time.

And, half a century later, it still did.

He said: “I had to go and tell his parents that their boy wouldn’t be coming back.

“The look in their eyes was awful.

“They had been hoping against hope that he would make it and they thought he had done it, because they didn’t learn of his death until after the Armistice.

“Later on, when my own sons (David and Bill) went off to war, I had some idea of what they must have endured.

“We all had to cling on to something at that time.

“With me, it was Burns, it was Lewis Grassic Gibbon (who wrote Sunset Song), but it was also some of the wartime songs from the 1940s.

“My wife (Jean) preferred A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, but I was always moved by We’ll Meet Again.

“It didn’t say we will meet again as young people, or even in this lifetime, but that it will somewhere or other down the line.

“Honestly, it made me think of Alistair and his parents and, while I wasn’t sure about an afterlife, I really wished there was for their sake.

“And for so many other families.”

That conversation happened more than 50 years ago, but I think it perfectly encapsulates the reason why Dame Vera Lynn is being mourned by so many from across the globe.

As with Judy Garland and Over the Rainbow, it springs from the melody’s faith in the belief that somewhere, somehow, there is a better place.