The swan song of Dame Vera Lynn set off a wave of nostalgia for her songs that were the backdrop to the war years for a generation. But not mine.

While I remember Dame Vera from the likes of Des O’Connor and Morecambe and Wise when I was wee, the soundtrack to my war era was a bit different.

Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s Two Tribes, Sting’s Russians, Kate Bush warbling about Breathing.

My war was the Cold War.

The tunes weren’t so much about meeting again as hoping we wouldn’t have our faces melted in a thermonuclear blast as Armageddon arrived.

People look back

with fondness on

Ronald Reagan.”

And that was before we started fighting rats for scraps of bacon in burnt-out basements in a post-apocalyptic landscape.

With 2020 vision we have more tangible world-changing events to deal with – the unholy trinity of a global pandemic, Boris and Trump.

So much so, there’s almost a sense of nostalgia for those heady days of the late 70s and early 80s. I mean, people look back with fondness on Ronald Reagan.

But back in the day there was a real fear the boy in the White House playing brinkmanship with the Soviets might just unleash nuclear hell.

It was reflected in the popular culture of the day. The aforementioned songs, plus a slew more, played into the idea World War 3 was just around the corner.

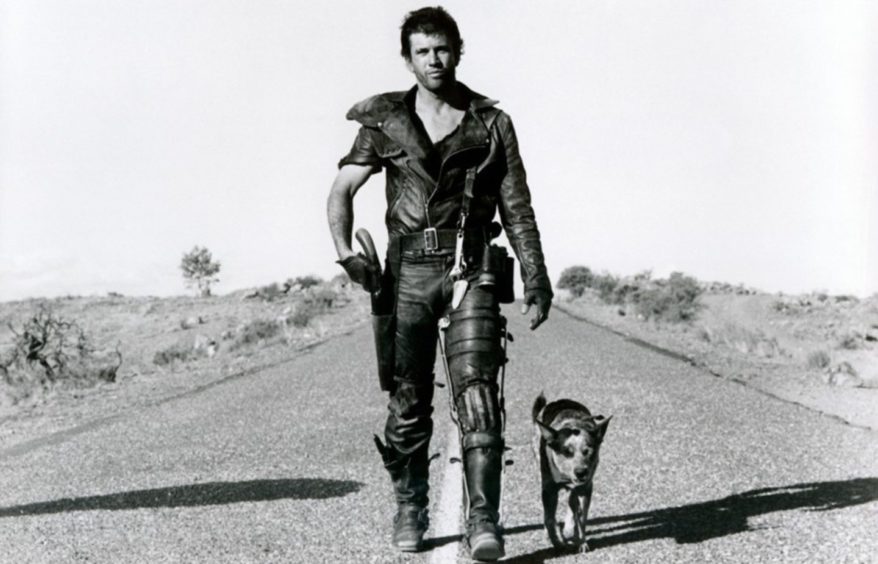

And our generation had been fed a steady diet of films telling us the end of the world was very likely nigh… from On The Beach in the late 50s, through to Dr Strangelove and to Mad Max.

It was in the early 80s all this ramped up a gear as Reagan made his Evil Empire speech about the Russkies and started deploying Pershing and Cruise missiles in Europe.

I was one of the band of folk who thought Maggie Thatcher was all a bit too willing to suck up to Reagan, too happy to turn the UK into a massive aircraft carrier for the nukes that would hit the Soviets. And they would be hitting us right back… cue the last scene of Planet Of The Apes.

We watched TV shows like Threads that painted the grimmest of grim pictures of how we could blunder into an all-out nuclear war, how it would affect ordinary folk and the bleak aftermath as the authorities tried to cope with society breaking down into barbarism.

There was one vivid scene of a badly injured traffic warden, armed with a machine gun, trying to guard a baying horde of civilians penned behind barbed wire fences. The dead would envy the living indeed.

Oh and check out When The Wind Blows. Raymond Briggs put the charm of The Snowman to one side to let us watch an elderly couple dying from radioactive poisoning in the comfort of their cosy home.

It wasn’t all fiction. This stuff was real.

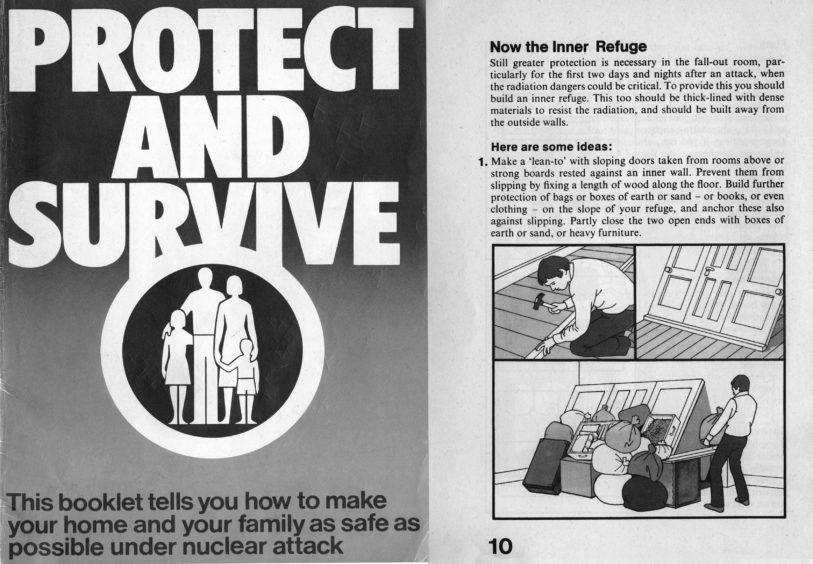

There was a government public information campaign called Protect And Survive, ready to be deployed if things started running really, really hot. There were films to be broadcast on all channels if war was imminent, pamphlets to be distributed to homes.

It ran us through the various alerts which would tell us an attack was on the way.

The four-minute warning was so called because that was how long it would take from a Soviet missile launch being detected to your home town being turned into radioactive slag.

It explained how nuclear blasts worked. We were versed in the difference between ground and air detonations and what a blast radius was.

Meanwhile the powers-that-be

had been busy carving out secret

nuclear bunkers to ‘govern’

the atomic wastelands.”

We were told how to build a blast and fallout shelter in our house, what the symptoms of radiation sickness were, how to put the bodies of our loved ones in a bin bag and bury them in a shallow grave outside with a toe-tag to identify them.

Meanwhile the powers-that-be had been busy carving out secret nuclear bunkers to ‘govern’ the atomic wastelands.

They litter the landscape, from Scotland’s Secret Bunker near Anstruther, to the little known ones. That includes one just two minutes from where I live, beneath the council’s Viewmount building in Stonehaven. I’ve been in it. It still had the shower at the double-door, air-sealed entrance to wash off the radioactive dust from being outside.

Of course, this civil defence information campaign was nonsense. I mean, it included how to protect yourself from a nuclear blast if you lived in a caravan. And no, it wasn’t put your head between your legs and kiss your backside goodbye. But it might as well have been.

This wasn’t about saving the public from a nuclear holocaust. Nothing would. It was to keep the populace calm and docile in the face of the inevitable, while the powerful made a dive for their bunkers.

Protect And Survive was more terrifying than anything fiction or song could offer.

No wonder there were CND rallies and anti-war protests a go-go back in the day. We’d rather not be left as soot stains on the pavement, thanks.

Dinner parties – as much a part of the era as the threat of intercontinental ballistic missiles – often turned to what you would do if Armageddon was about to break out.

The number of people who said head for the Highlands with a bottle of whisky would have made Braemar a bit of a bottleneck.

Then there was the inevitable “what would you do with your last four minutes if the warning went.”

I can actually answer this. On July 26 1986, the nuclear warning sirens went off in Edinburgh for 90 seconds by accident.

I didn’t hear it over noise of my hair dryer. Aye, I might have been blown to kingdom come but I would have looked great when I got there.

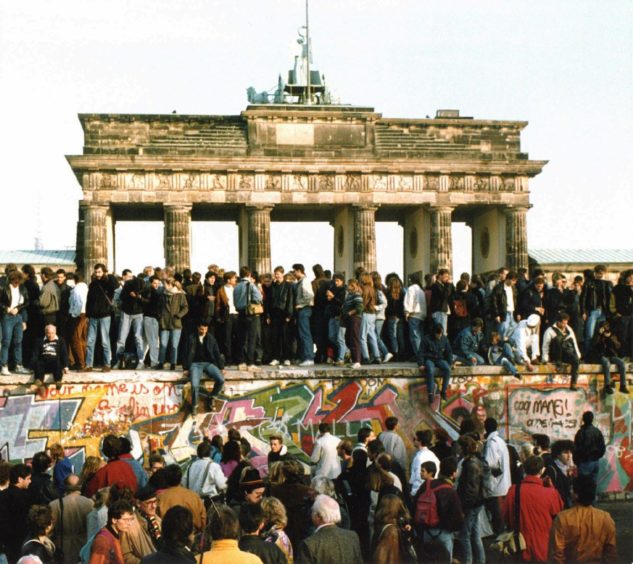

We finally got to breathe a sigh of relief when the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, signalling an end to the Cold War that had haunted our nightmares.

On the song front, we might not have got anything quite as poignantly enduring as We’ll Meet Again out of it – but Two Tribes is still a choon.