He was involved in some of the biggest blockbuster movies ever made which ranged from The Sting and Jaws to The Taking of Pelham One Two Three and From Russia with Love.

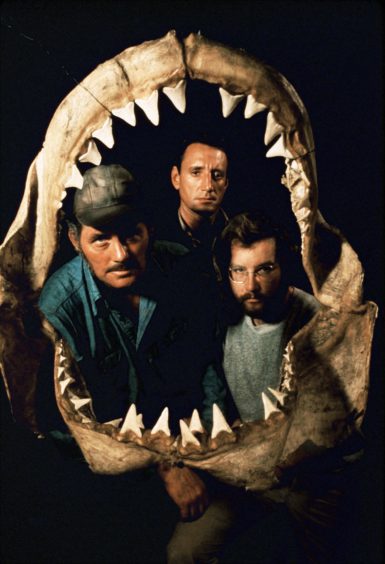

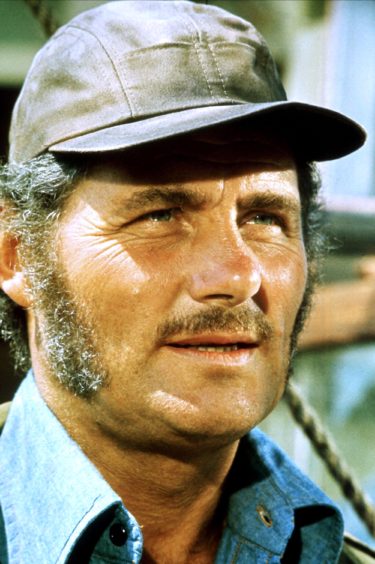

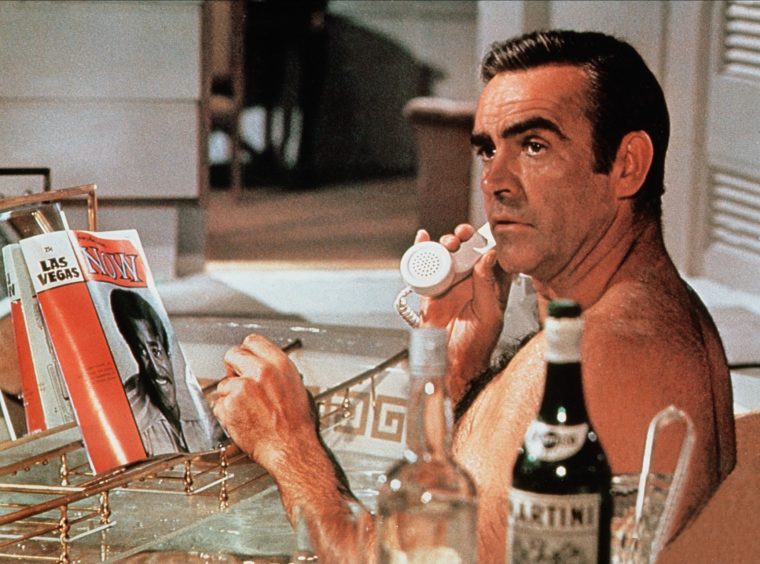

Nobody who watched Robert Shaw embroiled in a savage fight with Sean Connery’s James Bond on a train or behaving like a modern-day Captain Ahab in Steven Spielberg’s legendary shark tale on the vessel Orca will ever forget the animal magnetism which he brought to his performances.

In his film persona, he was brash, bold and invariably filled with bravado.

But, even from his days as a school child on Orkney in the 1930s, Shaw was a maverick; a troubled soul whose father, Thomas, was well-regarded as a doctor, but could not escape from the alcoholism which eventually led to him taking his own life.

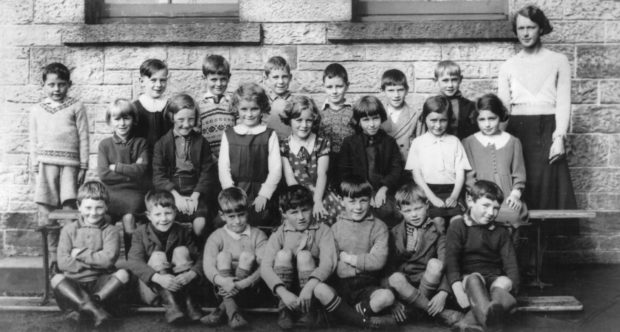

There is a picture of him with his classmates on Stromness and he strikes a pose by standing apart from the rest of the crowd.

It was a trait which later defined him.

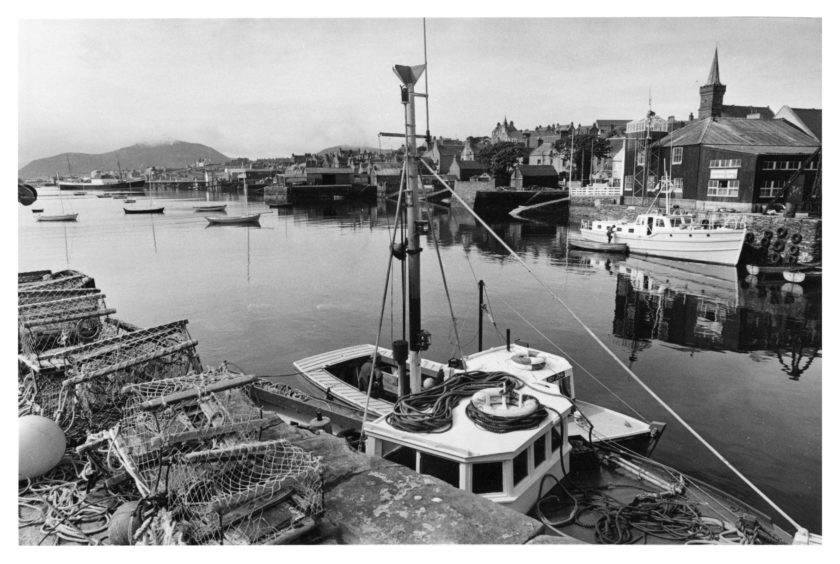

In 1933, Dr Shaw brought a small medical practice on Orkney and the family moved into a characteristic stone house overlooking the sea.

The remoteness of the setting made a profound impact on the young Shaw who later wrote about it.

He said: “The clouds hung over his head like the fitted sails of a great armada, swelling and swelling, dropping and dropping, till they almost touched the ground.

“His mother shouted him into the kitchen, closing the doors and windows fast shut. The little boy did not want to come inside, for he had never seen such stillness – the air so dense that the grass was sweating.”

As his friend, John French, later recalled, the youngster had to grapple with being treated as an outsider after he arrived on the island. And, if it was an arduous challenge for him, it was even more of a struggle for his father.

Mr French said: “The social climate was very different for the young Shaw. In Lancashire, he had been very much part of school life, but in Stromness, he was an outsider with a strange accent, who was called a ‘ferry-louper ’.

“His developing athletic prowess was snubbed and he was not picked for the school football team. Nor did his father’s troubles diminish.

“Dr Shaw was widely respected as a doctor, but his drunkenness, in a community that was well versed in drinking, soon became a matter of public concern. With only 2,000 inhabitants, gossip spread quickly and the practice suffered accordingly.

“It did not take long for his wife Doreen to realise that hopes of a change were short-lived and a series of rows followed. Her husband’s pledge to her that he would cut down on his drinking had proved worthless. If anything, his consumption had increased.

“She decided that if things didn’t improve, she was going to leave, taking the children with her. Things did not improve. In fact, they got so bad at one stage that Doreen moved the children and herself into the local pastor’s house in an effort to convince her husband that she was serious.

“Three years after moving to Stromness, she left and took her family south (to Cornwall).

“But in 1938, Dr Shaw told his wife that he was determined to kill himself.

“She did not believe him, as she had not done on all the previous occasions. But he went into his surgery and took poison. Robert was 11 years old.“

It was a tragedy which scarred the actor for the rest of his existence. No matter the plaudits he gained for his memorable appearances on the silver screen – and the rave reviews he was accorded by US audiences after his roles in The Sting and Jaws in particular – his life was persistently blighted by scrapes, setbacks and set-tos.

He became almost crazily competitive, constantly battling for top billing on film posters, and arguing about money and contracts; he was also driven by a need for children of his own and eventually fathered nine by his three wives.

His extravagance led him into trouble with the tax man and thereafter into unwilling exile, living in Orson Welles’ house in Spain, before it “accidentally” caught fire, resulting in damage to some of the prized artefacts from the legendary Citizen Kane.

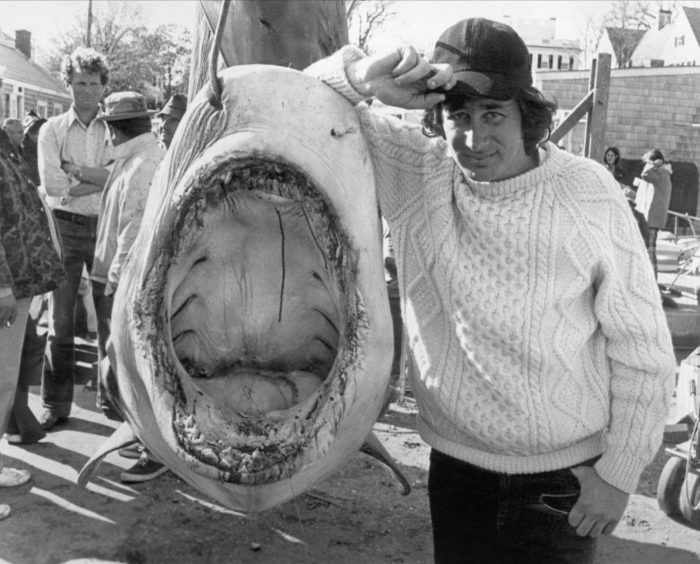

Although Jaws has become a cinema classic, the filming of Steven Spielberg’s movie was beset by problems, including the costs of shooting on water and the difficulties of operating a mechanical shark – which explained why it was mostly kept concealed.

There were also rumours of heated arguments between two of the leading actors, Richard Dreyfuss and Shaw, but the former has dismissed these as mere gossip.

He said: “It’s not true, and where that started I don’t know, but trust me, Robert Shaw wouldn’t countenance the idea of a feud, so forget it.

“I don’t know how to hold a grudge, but I lost my sense of humour for one afternoon. That’s not a feud – it was very simple and he had my number.

“He was walking down the gangplank, holding a drink in his hand, and said: ‘Richard, help me out here.’

“I said: ‘Do you really want my help?’ He said he did and I took his drink and I threw it in the water.

“Everybody on the crew went ‘Ooooh’ and then he got his revenge by taking the fire hose and pointing it at my face.

“I lost my sense of humour and that lasted about an hour before everything was fine again. The shoot was chaos, but it was all called for.

“The decision to make the film on the real ocean was the first mistake.”

Although Shaw endured plenty of misery on Orkney, he wasn’t totally detached from the island community and forged a close bond with some of his contemporaries.

Archie Bevan was one of the Orcadians who established a friendship with the young Shaw and he paid tribute to the actor in a piece which was broadcast on BBC Radio Orkney in August 1978, following the actor’s untimely death at the age of just 51.

Mr Bevan recalled: “Robert would have been about seven years old when he first came to Orkney in the early 1930s.

“The family settled in Stromness when his father set up his medical practice in the town. They lived in Seafield House, opposite the Bank of Scotland, the house from which Dr Cromarty later ran his medical practice for many years.

“The Shaws were a lively family. Dr Shaw himself was a great outdoor man, fond of shooting and fishing, and something of a bon vivant – at least by the douce Orkney standards of those days.

“Robert was two classes below me in school, an unbridgeable gulf at that age. But he was a classmate and companion of my cousin, Captain Arthur Porteous.

“His schooldays in Stromness made an enduring impression on Robert. When I met him again more than 20 years later, he recalled those days in vivid detail.

“He was able to name his classroom friends – and enemies – and he remembered the bitterness he had felt in the early days when he was ganged up on by a small clique – headed not by an Orcadian, but by an incomer like himself.

“Much later in his life, he was able to recapture the joy, and the anguish, of his Stromness days in some vivid semi-autobiographical writing in his first two novels – The Hiding Place and The Sun Doctor.

“The family left Stromness just before the start of the Second World War.

“It was 1960 before Robert Shaw returned to Orkney on holiday. By this time he had established a considerable reputation on the London stage.

“He had just begun his career in the popular cinema with a smallish part in The Dam Busters. He had already made his mark on TV with a starring role in a series called, I believe, The Buccaneers, but this was before the advent of TV in Orkney.

”He had already published his first novel, The Hiding Place, a work of high promise. He was busy writing his second novel, and he told me that he had no less than seven more books mapped out in his head.

“He returned to Orkney in the summer of 1963 with his second wife, Mary Ure, the Scottish actress who had made her name as the long-suffering wife in John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger.

“I remember that my first meeting with Robert that year was on the Stromness Golf Course. He was playing in a foursome with some members of the local club.

“His dark hair had been bleached to a startling Aryan blond, a remnant of his starring role as the villain in From Russia with Love, which he had just finished shooting.

“Of course, you’ll remember that he came to a sticky end, at the hands of James Bond, in that film, but Shaw told me that in fact he and Sean Connery were very close friends, and he had a great admiration for Connery’s ability as an actor.

”My most vivid memory of Robert that summer was a visit we paid to Rackwick. My family was camping in Hoy and we gave the Shaws a lift through from Lyness.

“As we turned in the valley under the shadow of the Ward Hill and the Dwarfie Hamars, he enthralled the youngsters in the car by launching into a delightful story featuring the Trow of Trowieglen.

“He was a born storyteller, with a great imaginative gift and wonderful way with words.

“He left Orkney shortly afterwards and I never saw him again. His performance in From Russia with Love set him on a road to stardom, which was to culminate in blockbusters like The Battle of the Bulge, Jaws and The Deep, although the fact is that some of his finest films never achieved box-office success.”

Shaw was capable of forging great friendships with many people across the acting and literary world and he became a cult hero when he moved to Ireland in the 1970s.

Those who met him still testify to how he was charming, charismatic and capable of terrific generosity – but he never acquired the knack of knowing when to say “Stop” once the drink started flowing.

However, it didn’t detract from the qualities which he brought to the stage and screen.

In a BBC “Omnibus” programme in 1970, Shaw was asked about his childhood and he had difficulty in responding to the question.

He said, finally, that he remembered his father, both sober and drunk.

When it was the former, Shaw declared that he was “flamboyant and a lovely man”.

But, when he was the latter, the actor added, with a frisson of pain: “He was troubled.”

Sadly, that description seems to have applied equally to both father and son.