He was one of Scotland’s most prolific and successful writers.

But Alistair MacLean, the creator of such novels as HMS Ulysses, Where Eagles Dare, The Guns of Navarone, Fear is the Key and Ice Station Zebra, was also among the servicemen who fought in the Arctic Convoys and helped liberate the Changi camp at the climax of the Far East campaign in the Second World War.

His visceral experiences during the hostilities, ranging from sailing in frozen waters, facing hurricanes, mountainous seas and the constant threat of U-boats to dealing with sweltering heat, lethal diseases and cockroaches “the size of small mice” provided the inspiration for many of his most famous works.

And his niece, Shona MacLean, the Inverness-born Aberdeen University graduate, who is also an acclaimed author, has spoken about her memories of her uncle, including the time when she smuggled two pounds of prime Scottish mince in a suitcase into Dubrovnik in Yugoslavia – prior to the formation of Croatia in the 1990s – on a visit to see her beloved relative.

MacLean, who was born on April 21 1922 in Glasgow, spent much of his childhood and youth in Daviot, 10 miles south of Inverness, and only learned English as a second language after growing up as a fluent Gaelic speaker.

In 1941, at the age of 19, he made his mark in a wider sphere after being called up to fight in the war with the Royal Navy, serving with the ranks of Ordinary Seaman, Able Seaman, and Leading Torpedo Operator.

He was initially assigned to the Bournemouth Queen, a converted excursion ship fitted for anti-aircraft guns, on duty off the coasts of England and Scotland.

But then, in 1943, MacLean served on HMS Royalist, a Dido-class light cruiser and was involved in action in the Atlantic theatre, on two Arctic Convoys and escorting aircraft carrier groups in operations against Tirpitz and other targets off the Norwegian coast.

In 1944, he and the Royalist were in the Mediterranean, as part of the invasion of southern France, helping to sink blockade runners which were operating off Crete and bombarding Milos in the Aegean Sea.

He spoke later about these convoys as “missions which pushed men to the limits of their endurance” and “where everybody lived in fear on a constant basis”.

He knew that if you ever landed in the water “you were lucky to survive for five minutes”.

When the ship returned to Portsmouth from the Aegean, Charlie Dunbar from Banff joined the crew for his first taste of life aboard a fighting vessel and, despite being apprehensive and wishing he back in Scotland, he soon struck up a friendship with his compatriot, the battle-hardened MacLean.

He later recalled: “He came over and asked where I was from and I told him I was Charlie Dunbar, the cinema projectionist at the Playhouse in Keith.

”Well, he smiled and said he was Alistair MacLean from the same north and north-east part of Scotland. It was a relief to find out I was no longer on my own and, thereafter, he looked after me and asked how I was settling in.”

In 1945, in the Far East theatre, the pair of them saw action while escorting carrier groups in operations against Japanese targets in Burma, Malaya, and Sumatra.

After the Japanese surrender on August 15 1945 – which will be commemorated as the 75th anniversary of VJ Day this week – the Royalist helped evacuate liberated POWs from Changi prison in Singapore.

MacLean and his mates were present for Lord Mountbatten’s ceremony of official surrender and were in time to see Japanese soldiers being forced to clean the parade ground, to the point of picking grass between the cobblestones.

He highlighted how Indian soldiers, who were incensed at what had happened to Allied troops in the prison camps, stood over them with bayonets, prodding them or kicking their backsides as a outlet for their rage.

That sight offered MacLean another reminder of the horrific conditions which many of the surviving captives had endured for many years.

He talked about the compassion he felt for these “poor lads, who were thin as rakes, with their ribs protruding through their skin” and expressed his belief that those who had fought in Japan were every bit as important as their counterparts in Europe.

As he said: “There were so many boys who had never even heard of places like Singapore, Burma and Siam. But they went there and too many never came home.”

MacLean was discharged from the Royal Navy in 1946 and studied English at Glasgow University, while working at the Post Office and as a street sweeper.

He graduated in 1953, briefly plied his trade as a hospital porter, and then embarked in a career as a schoolteacher at Gallowflat School in Rutherglen.

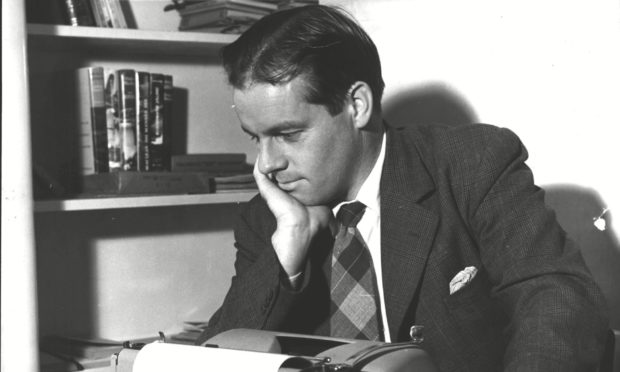

He had no grand literary ambitions, but decided to enter a short story competition in the Glasgow Herald. And then, from 1,000 entries, the winning tale by MacLean was published in the paper in March 1954, by which time Ian and Marjory Chapman were both editors at the Collins Books headquarters in Glasgow’s Cathedral Street.

After reading his successful submission, they were so impressed that they made contact with the author to suggest he should write a novel for their company.

But this idea was not immediately attractive to MacLean, as explained in his official biography by the north-east journalist Jack Webster.

He recalled: “Over dinner in the city’s Royal Restaurant, the rather dour Highlander expressed little interest in novels, saying he was content with the odd short story.

“He did, however, mention his wartime experiences on the notorious convoys to Russia, which prompted the Chapmans to enthuse about that as a subject for a book.

“But MacLean still showed little interest and they did not hold out much hope.

“Yet, less than 10 weeks later, they received a phone call with the message: ‘Do you want to come and collect this thing?’

“This thing. Yes, Alistair MacLean had written his book, so Ian Chapman hot-footed it to the furnished rooms at 343 King’s Park Avenue, where Alistair and his German wife, Gisela, had just had their first child.

“In the midst of a downpour of rain, Chapman was left standing on the doorstep, viewing an array of nappies while MacLean went and collected the manuscript.

“But then, once he was back home, he peeled open the sodden package on his kitchen table – and there in front of him was the title page of HMS Ulysses, which was destined to become one of the biggest best-sellers of all time.”

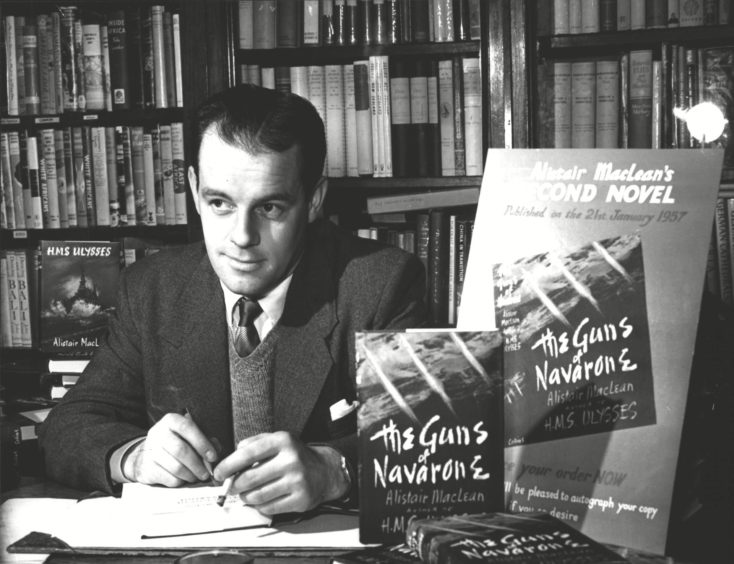

It was the beginning of a remarkable period in MacLean’s life where everything he touched turned to literary – and often cinematic – gold.

When he discovered that HMS Ulysses was being printed across the world, he wondered whether it would earn him enough money to enable him to put down a deposit on a new house at Hillend Road in Clarkston.

However, as Webster wrote: “Those detached bungalows being built in 1955 were costing £2,750 and the Collins advance was £1,000.

“But Ian Chapman’s private calculation that, within a short time MacLean would have grossed £100,000 was not misplaced.

“He could then have bought not only No 16, but the whole damn street!”

In the second half of the 1950s and 1960s, the Scot’s prodigious output was regarded as a licence to print money.

Although he occasionally declared that he regarded himself as a storyteller rather than a literary giant – and some critics were sniffy about his endeavours – the public and film executives lapped up MacLean’s rip-roaring stories such as The Guns of Navarone, Ice Station Zebra and Where Eagles Dare.

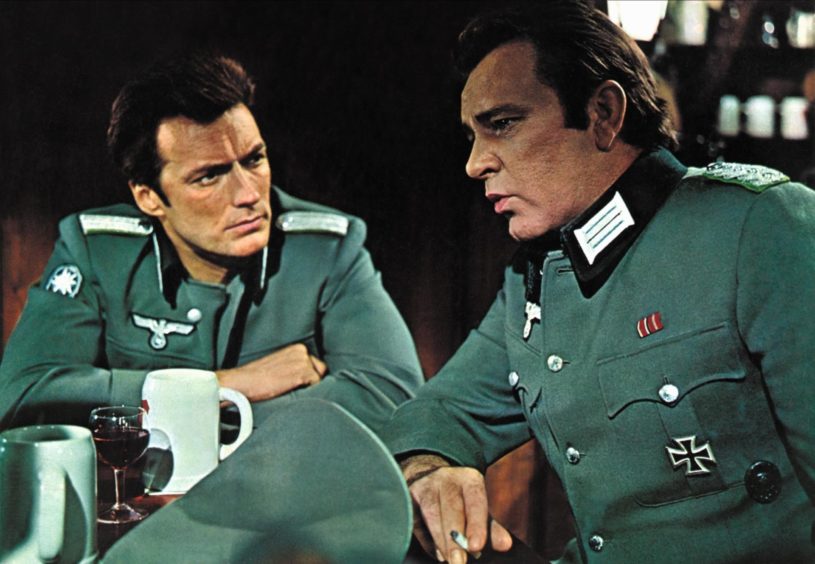

The latter was turned into a smash-hit movie, starring Clint Eastwood and Richard Burton, but the Welshman and MacLean did not always see eye to eye, which led to one spectacular Donnybrook between the duo.

The setting was the plush Dorchester Hotel in London’s Park Lane. And although Burton, on screen at least, was accustomed to shoving his weight around, it was a different matter when he squared up to MacLean during a drunken brawl.

The author may have been slightly-built, but he landed a powerful right hook to Burton’s nose, sending him sprawling into unconsciousness.

There was a poignant epitaph to that acrimonious encounter when both men died, MacLean aged 64 in 1987 and Burton at 58 just three years earlier.

Despite their peripatetic lives, their relentless wanderlust and their often chaotic private lives, the duo ended up being buried at the same site in Switzerland.

Jack Webster travelled to Celigny to meet MacLean’s first wife, Gisela, and that was the prelude to an evocative afternoon for the pair.

He said: “On a subsequent visit, Gisela asked me if I would like to see Alistair’s grave.

“So we wandered along to the cemetery, an unpretentious little place where the first grave on the left might well have belonged to a local labourer, except for the fact that the headstone told a different story: Richard Burton.

“Across the narrow pathway, just a few yards away, we came upon that other stone, marking the last resting place of the warm, wayward, fallible human being: Alistair MacLean.

“And there they lie in peace forever, near a waterfall which tumbles down a little ravine like a sparkling Highland burn.”

In death, as in life, there is always a compelling story with MacLean!

Memories of my uncle Alistair MacLean by his niece Shona

My earliest memories of Uncle Alistair is as a name across the TV screen at the beginning of a film, or along the spines of many books in our house.

From these early visits, I remember a small, quiet man who dressed just like my dad and seemed out of place with the paraphernalia and fuss around him – mainly generated by his second wife.

It was as a teenager that I got to know him better. He seemed to come home to Scotland more often in the last decade of his life, and we went on holidays to visit him in Cannes and then Dubrovnik.

Still he dressed just like my dad. There would be large dinners at night – I distinctly remember being struck, at about 17 early in a holiday in Dubrovnik, that people around the table were talking about food as if it were art or great literature, rather than ‘very nice’, ‘too salty’ or ‘a bit dry’.

I had never heard people talk about food this way before.

Uncle Alistair, however, would hand back his menu and ask for a piece of grilled fish with boiled potatoes.

On one occasion, my sister and I had had to smuggle two pounds of mince from our local butcher for him, and a packet of pork sausages, into Yugoslavia in our suitcases.

Uncle Alistair’s friend Avdo, a former hotel manager whom he employed to look after everything and whose house overlooked a beautiful inlet of the Adriatic where he lived, ensured that everything went smoothly at the airport.

Avdo’s wife Inge was a successful artist, but she always made sure that uncle Alistair was properly fed and cooked the mince according to his instructions.

He was incredibly generous, but also very interested in our plans for the future.

Being summoned to be interrogated was daunting. When my parents brandished my school report at him one year, when I had done very well in English, he asked me if I wanted to be a writer.

He then gave me one of the best pieces of advice I’ve had – “If you write something and an editor tells you to change it, you change it. I never change anything, but that’s because I’m me – you change it”.

I have had the same editor for 12 years, and never had cause to argue with his advice.

My uncle died years before I eventually started to write, but when I was working on my own first book, I wondered what kind of readership I was writing for.

And I realised that I was writing something I hoped my father and his brothers, who had been brought up on Walter Scott, John Buchan and Robert Louis Stevenson, would have liked.

The thoroughly delightful S.G. MacLean, whose The Redemption Of Alexander Seaton is our July Scottish Book of the Month, will be here to talk about her work on Thursday the 25th at 6pm.

The event is free. All are welcome. Come along and meet a genuine local celeb! pic.twitter.com/tm4z0CUpDW

— Waterstones Inverness (@WatInverness) July 8, 2019

I could give lots of instances of his generosity, but the thing that stays with me most happened years before I was born, and before anyone had heard of Alistair MacLean.

After the end of the Second World War, my father – Alistair’s younger brother – was stationed in Berlin. He was very badly injured in a grenade attack and transported back to Britain, to a convalescent home in England.

Uncle Alistair was, by this time, a student at Glasgow University – I later heard from someone in publishing who had been in his class that they had never seen him because he was always working at one of the several jobs he took to make ends meet.

Alistair nevertheless managed, every fortnight, to hitch a ride down to England to visit his younger brother and report back to their widowed mother in Glasgow. My father had been so badly injured he didn’t even know he was there.

The day uncle Alistair died, my father went with my mum up to Daviot, where they had been boys, and my mum told me that he cried.

I never saw my father cry.

Shona MacLean has written a series of popular books, following the success of her debut novel The Redemption of Alexander Seaton.