By any standards, August 18 1985 was an auspicious day in the annals of Scottish sport.

On the golf circuit, the recently-crowned open champion, Sandy Lyle, shot a terrific eight-under-par 64 to win the Benson & Hedges International tournament at Fulford; emerging athlete Tom McKean surged to victory in the 800m to boost Britain’s hopes at the European Cup in Moscow; and, most romantically of all, Freuchie booked their passage to a Lord’s final in the National Village Cup with a riveting roller-coaster victory over Leicester rivals Billesdon at the Public Park in Fife.

Howver, there was nothing easy about the fashion in which Dave Christie and his team secured their passage during a contest which often seemed to be slipping out of their grasp. It rained as if the heavens had decided to feel really sorry for themselves.

Then there was a near-mutiny among the Scots as the game was splashed out in circumstances which occasionally bordered on farce.

The English side had flown home their wicket-keeper-batsman, Ian James, from a holiday in the United States, so that he could participate in the semi-final, and were bolstered by a fine opening bowler in John Ford and a cerebral captain, Graham Butler, who exhibited the same unstinting commitment throughout the cup campaign as his counterpart, Christie.

However, even before a ball had been bowled, a blanket of rain enveloped Fife, and called into question whether the conditions were fit for play.

Undaunted, the opposing skippers met and settled on a gentleman’s agreement whereby, no matter how dismal the weather became, they would stay on the field and avoid a dreaded bowl-out if it was remotely feasible.

It was a lovely gesture, although the pact provoked furious debate later in the proceedings, but when Christie lost the toss and his men were asked to bat, there were ample reasons for the 1,ooo-plus crowd to be apprehensive as soon as Ford entered the scene, adroitly orchestrating the action and twisting the plot.

A clatter of wickets threatened to leave the Scots’ hopes in tatters and they were soon in dire straits at 19 for 4 in the 10th over, their Lord’s aspirations sinking by the moment.

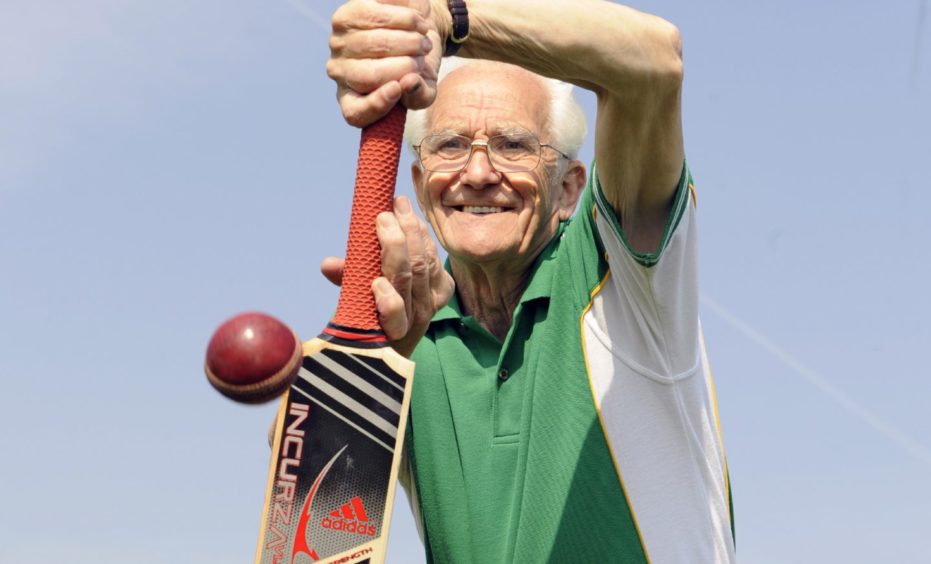

Thankfully, though, George Crichton, a grit blaster with a steely approach to wielding the willow, emerged to take centre stage, as the atmosphere cranked up.

He said: “We didn’t make a decent start in any round of the competition that year, and although we seemed capable of retrieving matters, Billesdon were a seriously good side and I knew that if we were all out for 80 or 90, we would be beaten.

“It was one of those situations where you have to forget about the weather or the pitch and play every ball on its merits. That sounds simplistic, but when you looked at the faces of the spectators, who were packed into the ground, it was clear they feared a rout and, given how much Freuchie meant to me, that was enough incentive to do my Barnacle Bill act. I had nothing against the English, but the bottom line was that only one of us was going to Lord’s and I was determined to make sure it wasn’t them!”

Yet, irrespective of Crichton’s contribution, wickets kept tumbling at the other end, as the war of attrition continued. Briefly, Davie Cowan inspired cheers with a six, but fell soon afterwards to the medium pace of Bill Armstrong, whose efforts stymied the Fifers’ attempts to generate any sustained momentum.

The home fans applauded every run as 80 became 90 and they whooped when the 100 was achieved, but although Crichton clung on tenaciously until the 38th over before being bowled by John Elliott for 28, Freuchie could manage no more than 117 and the worry etched on the faces of their aficionados at the halfway point told its own story.

“None of us had any illusions during the interval – we knew that we would have to make quick inroads when their innings began and prevent any of their batsmen from getting into their stride, otherwise we were done for,” said the late Niven McNaughton.

“All it would take was for one of their lads to hit 40 or 50 and we were snookered and, understandably, nobody was cracking jokes while we were eating our sandwiches.”

As sheets of rain enveloped the village, Billesdon’s openers, Butler and James marched out in the knowledge that all they required was patience. A run rate of below three an over meant their opponents were unlikely to stem the tide without early scalps.

Yet, precisely when it was needed, Cowan was stinginess incarnate and McNaughton soon claimed the precious wickets of Butler and Rob Nourish.

James and Elliott remained as major obstacles, with the contest balanced on a knife edge. The competition regulations dictated that Billesdon had to bat a minimum of 20 overs before a result was possible and gradually their task grew more difficult, with the ball sticking in the mud, and the boundary beginning to resemble a swimming pool.

By now, any pretence at sangfroid from the participants had vanished completely. They were slugging it out in classic Las Vegas heavyweight style for a Lord’s appointment.

Elliott crashed one delivery into the car park, but perished in striving to repeat the feat for 27, where upon the resilient James slipped in the glaur and was run out for 15, as Billesdon were reduced to 62 for 4.

But the Ford brothers, John and Dave, batted sensibly, sprinting singles and rotating the strike, and their partnership mounted as the climax loomed into view, with the weather deteriorating and tempers fraying among several of the combatants.

Crichton recalled: “It was crazy. We were all soaked to the skin, and we would have won on run rate, with the umpires offering us the chance to abandon the match, but Dave kept harping on about gentleman’s agreements, and I just told him: ‘Sod that!’

“We shared a frank exchange of views and although I might have been reacting in the heat of the moment, I stand by my argument that we had already gone the extra mile to get the match finished and there comes a time where you have to put up your hands and decide that enough is enough.

“I had total respect for Dave’s behaviour and it was really nothing more than you would have expected from the man. But, at the time, I could happily have shot him!”

For a brief period, Dad’s Army was imperilled by the risk of mutiny, but, mercifully, most of his personnel realised that Christie was doing the decent thing even if the fellow himself told me he was never as worried as during the fraught denouement.

He said: “I had given Graham Butler my word that we would stay out there, come what may – short of a tornado or an electrical storm hitting Freuchie – and I had to stick to my promise, but the thought kept flashing through my mind: ‘Jesus, if this backfires, I’ll never be allowed to walk into the clubhouse again’.

“The ball was wet and the outfield was treacherous, so I guess that we were being penalised by the conditions. But equally, they had travelled all that distance to get to Fife, so it would have been pretty shoddy if the result had boiled down to us scraping home by a narrow percentage on run rate, due to the weather.”

The words embodied Christie’s philosophy to his beloved game and explain why he is held in such regard throughout the sport in Scotland.

Despite the grumblings from the sidelines, he re-entered the attack and steadied himself for what promised to be a critical period. With the Ford siblings still at the wicket, Billesdon advanced to 88 for 5 and required 30 runs from the last 48 deliveries.

But suddenly, in the space of three frantic minutes between 7.15 and 7.18, both these redoubtable characters had been removed and the balance swung inexorably in Freuchie’s favour. The English tail-enders had no answer to the nagging accuracy of Christie, who accounted for both Armstrong and John Stimpson, to finish up with figures of three for 11, and eventually, Freuchie bowled out their foes for 105 to book their coveted place in the National Village Cup final.

The skipper said: “I remember crumpling in a heap for a few seconds at the finish and I was knackered: mentally, physically, emotionally, the lot.

“It had been a titanic struggle and there was a huge outpouring of joy from all of us when we grabbed the last wicket and victory was ours, but it was definitely tinged with a massive feeling of relief.

“I received the man of the match award and was given a Duncan Fearnley bat, but without being disrespectful to the sponsors, that was fairly irrelevant in the grand scheme of things and I felt very sorry for Graham, because both teams had given their all that Sunday and either of us might have prevailed in the end.

“It was funny. We had dreamt about going to Lord’s for so long, but there was a wee period at the end when things were pretty quiet. I am not over-dramatising it, but I am convinced that reflected the fact that we had been put through the wringer by Billesdon and we had been tested to the very limits of our abilities.

“Yes, we passed the exam, but, believe me, it was a hellishly tough ordeal.”

Ultimately, Freuchie were where they wanted to be. They were where any cricketer with a sliver of romance in his soul would want to be.

Their supporters began making travel arrangements, booking buses, faxing hotel reservations, and the club committee dealt with a splurge of media inquiries as Scottish cricket gained some well-deserved publicity.

Soon enough, Christie’s personnel would learn that they were up against the supposedly crack Surrey outfit, Rowledge, in the showdown in London. But, by that stage, the Fifers were frightened of nobody and relishing the challenge which lay in store.

It added up to an unparalleled occasion in the history of Caledonian cricket.