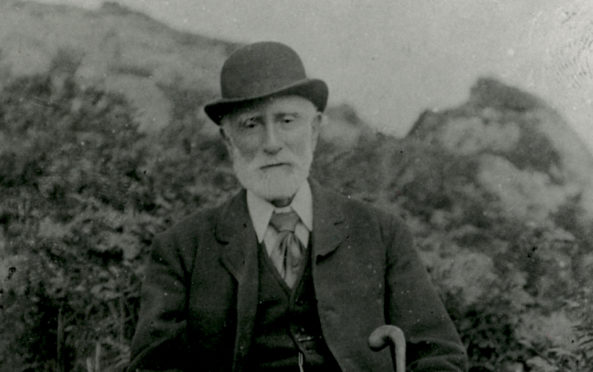

He was one of the men who helped create a flourishing railway network across the Scottish Highlands.

And Murdoch Paterson’s pioneering endeavours in often treacherous terrain and awful weather conditions, alongside other intrepid engineers, mechanics and labourers, helped establish a gateway to the north for future generations of travellers.

It’s 150 years this month since the former Inverness Academy pupil, born in 1826, was instrumental in the opening of the Dingwall to Stromeferry route, which had posed so many challenges for its creators – but nothing seemed to faze the redoubtable Mr Paterson, whose career is a testimony to the virtues of ingenuity and hard graft.

After leaving school, he took up an engineering apprenticeship with Joseph Mitchell who led the Highland Roads and Bridges commission in the city.

That organisation had been established by the British Government to examine the state of roads and bridges in the Scottish Highlands and build new ones where required.

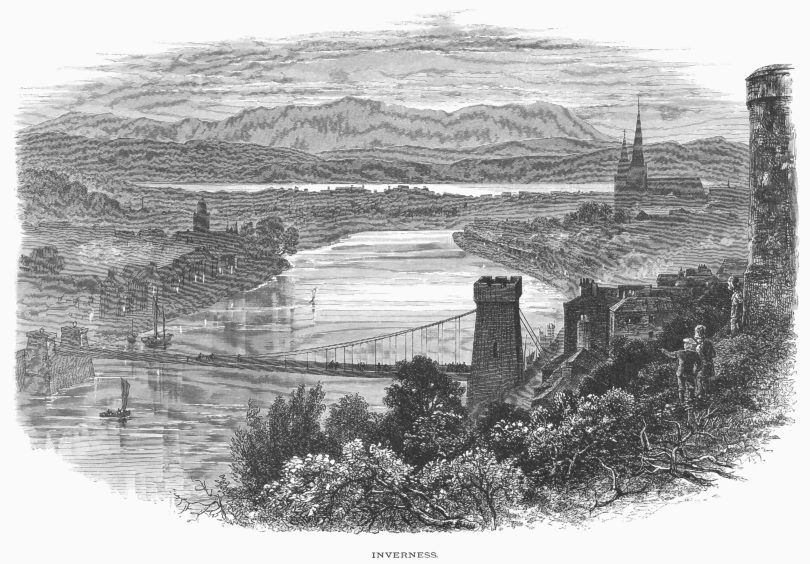

Following the completion of Mr Paterson’s apprenticeship, he took a job with a company which was carrying out work at Inverness Harbour including building a bar to give more protection to ships which were going in and out of the River Ness.

However, when the company went bankrupt, he showed his initiative in being the catalyst for the completion of the work to the authorities’ satisfaction.

It was to become a microcosm of his long and productive career: one which encompassed a series of Victorian values which are well worth celebrating.

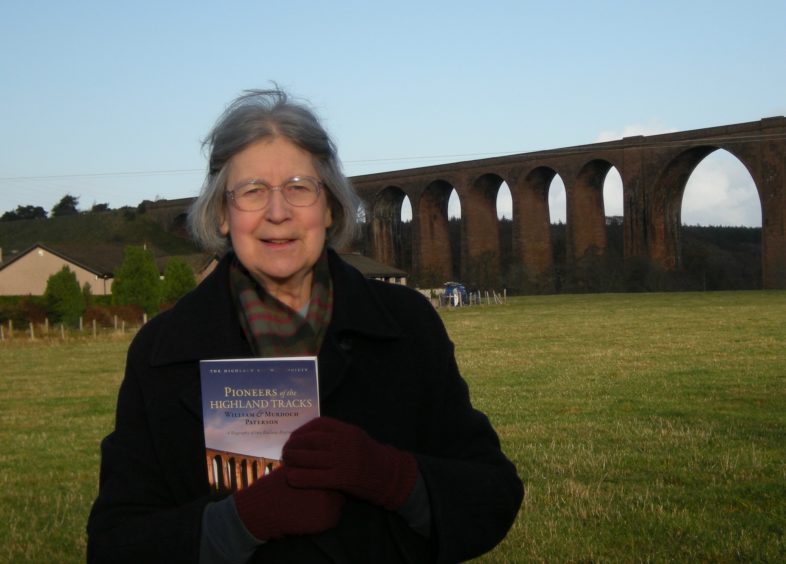

Anne-Mary Paterson, his great grandniece, has investigated his works and those of his brother, William, both in her own books and by appearing in several television programmes, including Great British Railway Journeys, and she is understandably proud of her ancestors.

She said: “By the late 1860s, plans were afoot to commence building railways from Inverness, first to Nairn, so Murdoch returned to work for Joseph Mitchell for whom William had been working since the late 1830s after gaining experience surveying railways in Ireland and building them in Central Scotland.

“Murdoch was the resident engineer for a number of railway lines: these included Inverness to Nairn, which opened in 1855; Nairn to Elgin and Elgin to Keith in 1858; and Inverness to Dingwall in 1862.

“The Highland main line from Perth to Inverness via Forres opened in August 1863 and reached Bonar Bridge in Sutherland from Invergordon in October 1864.”

This was a dramatic period of expansion for trains and the launch of new routes as thousands of customers across Britain revelled in the age of steam.

Murdoch Paterson was at the forefront of a hectic schedule of work all across the Highlands, including the service which will celebrate its anniversary this month.

Anne-Mary Paterson added: “The Dingwall to Stromeferry route received parliamentary approval in July 1865 and opened to the public in August 1870.

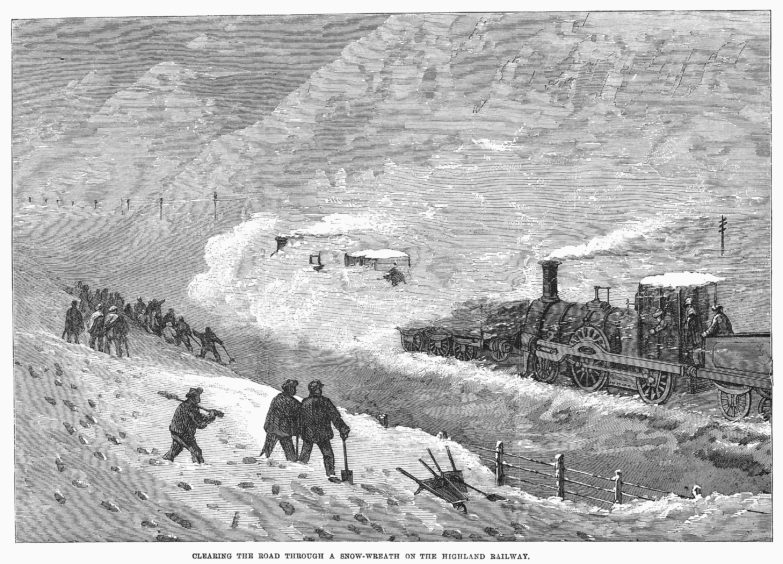

“His duties, as well as designing new lines, included the maintenance of all the lines.

“This was carried out by a whole army of staff in charge of keeping the railway open in sometimes difficult weather conditions, especially in winter when there were heavy snowfalls.

“Always thoughtful about the welfare of his staff, he had what he called the snow block special, a carriage which dispensed food and other refreshments for the men who were digging out the train.

“Murdoch never asked staff to do a job he wouldn’t do himself and wouldn’t hesitate to take off his jacket to show how a job should be done or join in completing a task.

“It is not known if he was a Gaelic speaker but, as many staff came from the Islands and the West Coast, it is probable he knew something of the language.

“It was Murdoch who in effect was the engineer for the proposed line to Kyle of Lochalsh from where the ferry to Kyleakin on Skye operated.

“Because of the mountainous terrain, there were not a great variety of routes that this railway could take. One was through Strathconon and on to Strathcarron and the other to Garve and through Strathbraan to Achnasheen. The first would bypass Dingwall and Strathpeffer, which was by then an aspiring spa village.

“Murdoch may have wished that a quieter route through Strathconon had been chosen as the proposed line had hardly left Dingwall when the first objection appeared from Duncan Davidson who owned land on the north side and lived in Tulloch Castle.

“He had originally been in favour of the railway, but when the plans were drawn up, he changed his mind, due to its impact on the Dingwall Canal and his estate.

“He consulted an engineer in Edinburgh, withdrew his support and because the bill had been deposited at Parliament, the negotiations were halted.

“The next problem was with Sir William Mackenzie of Coul. After passing Strathpeffer on its south side where the station would be situated, the line passed about a quarter of a mile to the rear of Coul House and then along the valley to Garve.

“In an effort to get an agreement, the railway offered to have about one third of a mile in cut and covered with landscaping to his specification. This was to no avail to Sir William, so a new route had to be found.

“This involved a climb to Raven’s Rock on land not far from Castle Leod and the Countess of Cromartie owned the land. She was the wife of the 3rd Duke of Sutherland, a director of the company. He was very keen on railways and went on to be involved with the building of part of the Far North line to Wick.”

There seemed to be one problem after another with the scheme as the months passed. Mr J R Shaw, who owned the Glencarron Estate and the lodge, decided that he would only allow the railway to pass through his land if he was provided with a private platform and siding.

The Highland Railway agreed to this, but asked him to purchase £2,000 of shares. He refused and the matter entered into a complicated arbitration process before he was awarded £450 compensation, £50 less than the railway had initially offered.

But although the railway provided a private platform, another headache soon materialised. Lord Hill, owner of Achnashellach Lodge who had originally been a member of the committee, was unhappy because the line passed in front of his house.

The deviation to which he agreed went behind the lodge, but this resulted in a sharp climb up the mountainside on what was otherwise a steady downhill passage.

Once again, the matter went to arbitration which resulted in the railway having to provide a private platform and siding.

All these delays and complications posed problems, but it was a measure of Mr Paterson’s patience and perseverance that the project continued to make progress.

Although the original idea was for the railway to go all the way to Kyle of Lochalsh, the expense of driving the line through hard rock, involving a large amount of blasting, was considerable and the directors decided to terminate the line at Attadale on Loch Carron.

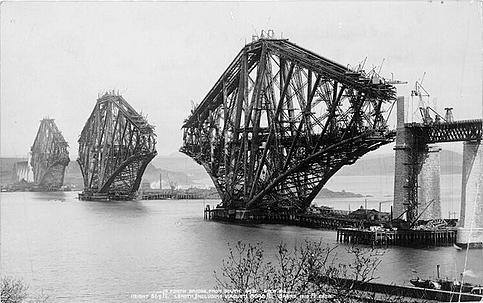

And there was also the arrival of a new director of the company, John Fowler, later Sir John, who with Benjamin Baker, was the engineer of the Forth Railway Bridge.

None of these issues helped the men, such as Mr Paterson, who were working at the sharp end. Even today, in the 21st century, many building ventures invariably end up taking longer than anticipated to complete.

But delays are an engineer’s nightmare and if they are not properly addressed, tend to escalate. He and his assistants were fully aware of how the clock was ticking.

Anne-Mary Paterson explained: “In this case, it was the section which ended at Stromeferry, which was being constructed by A & K MacDonald, which seemed to be dragging on interminably.

“Murdoch told them to hurry up. A group of directors, led by the Duke of Sutherland, inspected the work to find out the position.

“They were reasonably optimistic and so arranged for the Board of Trade inspection to take place on July 11 1870. Murdoch was not happy about this, as he knew the work would not be completed by that time, so he asked for a two-week delay.

“Captain Tyler, the inspector, arrived on Thursday July 28 for the inspection which took until Saturday. He was pleased with everything and the work of the resident engineers, J Cook-Gordon and John Fraser.

“However, he was not pleased with the fencing and so did not authorise the line. He returned on Monday August 8 and was still not satisfied.

“Nine days later, Murdoch sent a telegram to confirm that the fencing was complete. Captain Tyler gave approval to the line opening, subject to another inspection.

“And then, the first passenger train ran on Friday August 19.“

Although it was not open to passengers, a lavish banquet for civic dignitaries had been held at Stromeferry on August 7 in the engine shed.

A special train ran from Inverness to convey those attending.

On arrival at noon, the guests embarked on a cruise round Plockton and enjoyed the experience prior to sitting down to a transcendent meal.

The Inverness Courier reported on the event and quoted the praise given to Mr Paterson for “never missing an opportunity of saving expense, when such was possible, consistent with efficiency”.

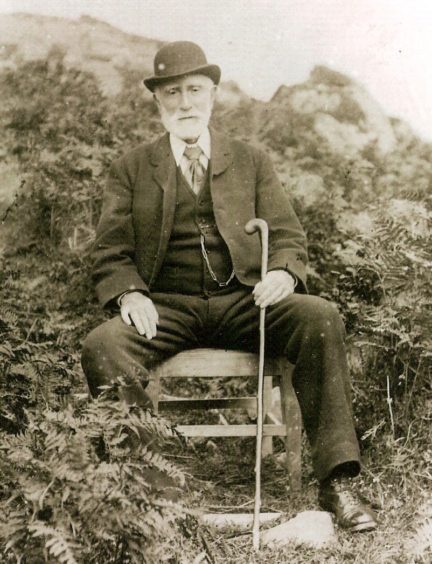

True to type, this hardy individual refused to rest on his laurels. He was involved in the extension of the line to Kyle of Lochalsh from Stromeferry, which opened in 1897 – and is now one of the Great Train Journeys of the World – and on the new direct route from Aviemore to Inverness which came to fruition in 1898.

By that stage, he was 72 and well past the usual age of retirement. And the strain of all his long decades of service, together with the many soakings and chills he sustained without any protective clothing, finally took its toll.

The Culloden Viaduct, a few miles south of the Highland Capital, is considered by many people to be his crowning achievement.

But, as Anne-Mary Paterson said: “He was so weak by the time it was near to completion that he did not have the strength to walk across the viaduct.

“So his faithful assistant, William Roberts, organised some of the men to push him across the viaduct in a bogey, so that he could give his last orders.

“Satisfied that everything was in place, he died a few days later.”

When the funeral cortège left his home in Inverness, en route to Tomnahurich Cemetery, the shops in the town were closed, the blinds drawn, and the streets were lined with mourners.

It was no more than this resilient and conscientious worker deserved.