It’s a life which has been the catalyst for Alec Crawford becoming fascinated with the joys of wrecks.

Whether hunting for ancient galleons or modern container ships, grand ocean liners or functional trawlers, the Fifer has spent decades diving into the deep blue yonder and unearthing precious artefacts and challenging himself on salvage operations.

He has spent more than half a century on and under the water from the Western Isles to the Mediterranean and the United States to Vietnam and South Africa, exploring the remains of such ships as the SS Politician, which was made famous in the classic Compton Mackenzie novel and Ealing film Whisky Galore.

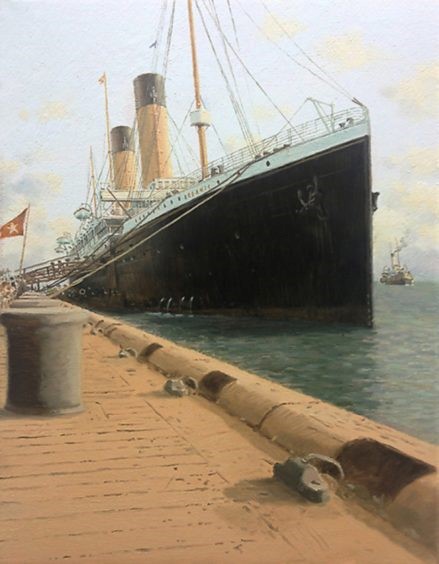

And he was at the forefront of the search for the White Star vessel, RMS Oceanic, which, when it was launched in 1899, was the largest ship in the world.

Even now, Mr Crawford, who met and married his wife and long-term business partner, Moya, in the remote setting of Foula, speaks with a thrill in his voice at the memory of that adventure which forms a major part of his new book Treasure Islands.

On August 25 1914, amid the outbreak of the First World War, the newly-designated HMS Oceanic started patrolling the waters from the north Scottish mainland to Faroe. But, on September 8, she ran aground and was wrecked off the island of Foula.

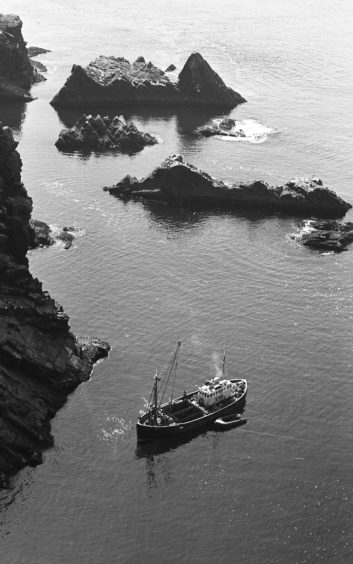

Locating the lost vessel was a hard enough task in itself – but the treacherous waters off Shetland made that salvage mission the challenge of a lifetime.

He and his colleagues spent months trying to locate and confirm they had discovered what was left of the Oceanic; like gold prospecting, this is one of the few opportunities for individuals to start out with practically nothing and make a fortune.

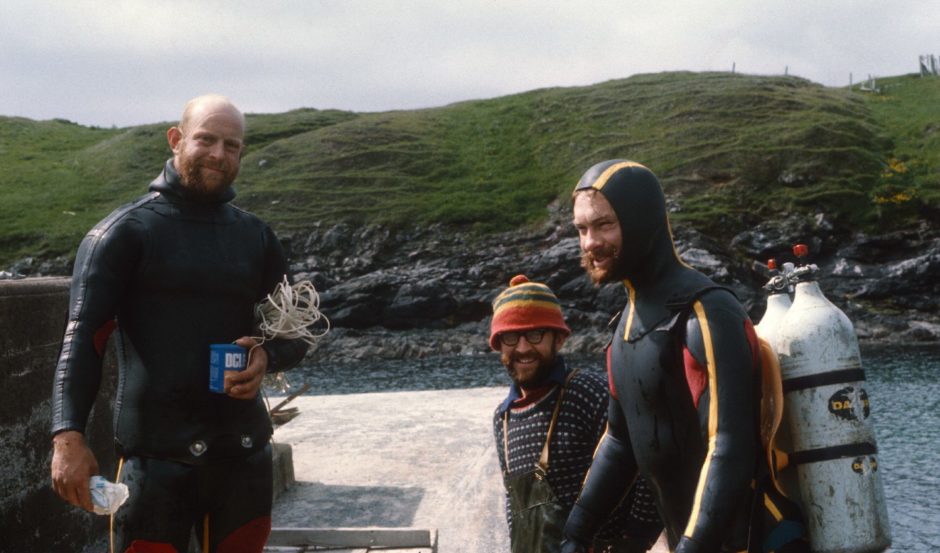

When Mr Crawford, who was just 23 at the time in the early 1970s, and his diving partner, Simon Martin, pursued the mission, they faced peaks and troughs and atrocious conditions and they had to be constantly ingenious and resilient.

But then came the realisation that they were in the right place for a magical experience.

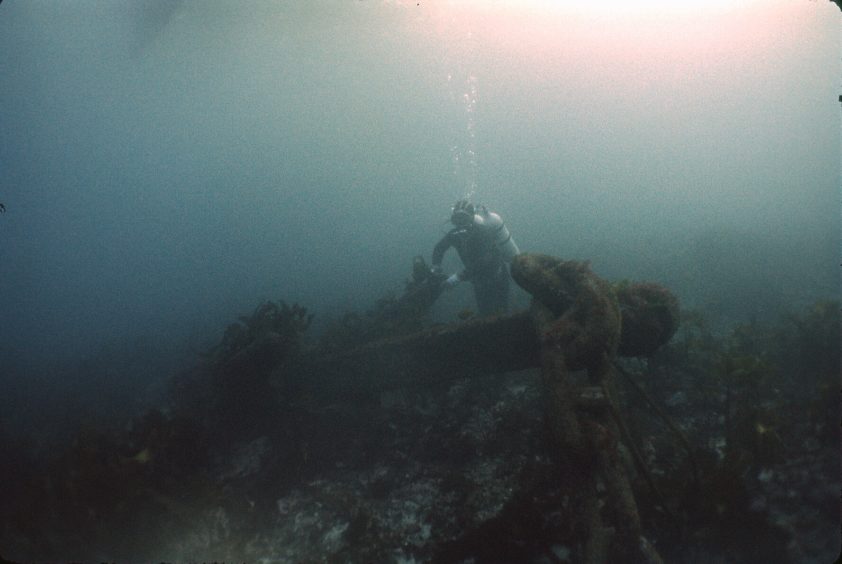

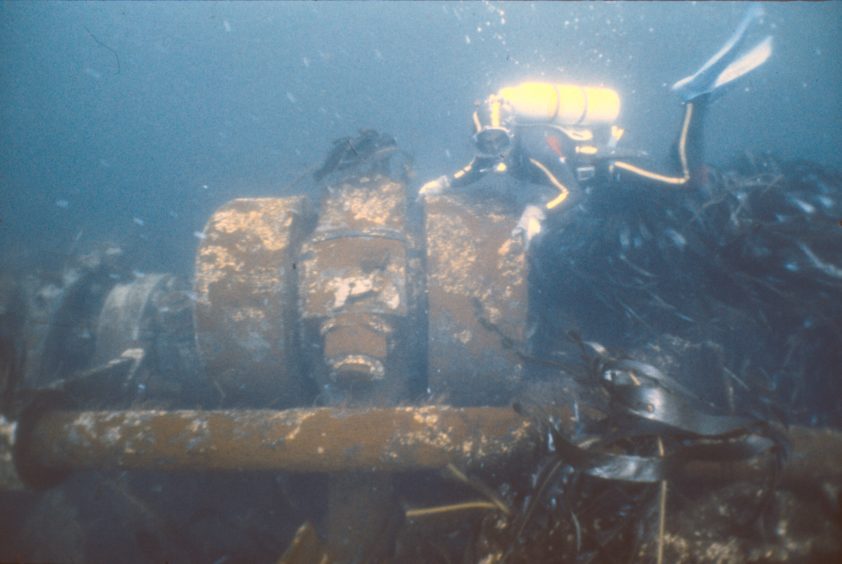

He recalled: “I dived first and lost no time in finding as much scrap as possible. I had little time to spend exploring the site, but when I swam past a boiler, I saw the cast engines towering behind it in the clear Shetland water.

“I now knew without doubt that we had discovered the wreck of the Oceanic. These were the enormous pieces of machinery which had pushed her across the Atlantic on her weekly voyages, the stokers shovelling coal up to the rate of 700 tons a day.

“The wreck was like nothing I had ever seen. The two steam engines were almost the same in size as the two outer turbines on the Titanic and although it was in pieces, you could quickly start to realise the giant scale of the vessel.

“The 15 enormous boilers and engines required 200 men in the engineers’ department to keep them going. I swam along the port engine crankshaft and it weighed 110 tons and had vast bearings on it to allow it to turn.

“The sides and deck of the ship had all collapsed, so it really could not have been better for us – all the parts we wanted were exposed, making them accessible.

“It was hard work, it was very hard work, and it took a good number of days before I had the time to swim as far as I could towards the propellers, one of which was partially buried in wreckage and debris.

“We had to sketch out what we wanted to do, because we knew the three-bladed propellers would require some serious blasting before we could make them small enough to lift aboard the size of boat that we could work from Foula.”

That was only the start of a protracted fight against a number of legal obstacles, while negotiating all manner of logistical issues and carrying out the frequently dangerous dives to retrieve parts and sections of the Oceanic.

Yet, as Mr Crawford said, there was never a time when he wasn’t thrilled at the prospect of unearthing a genuine piece of history which had lain for decades in the far north of Scotland.

He added: “In the 1970s, risks weren’t assessed in anything like the same way that they are today. We had a lot more freedom to take part in these dives and, looking back, I feel privileged that I had the chance to get involved in salvage across the world.

“It was a huge undertaking and although I was driven by the commercial opportunity in looking for the Oceanic, there was also a tremendous sense of excitement from the idea that you could be the first to discover a legendary wreck that nobody else could find.

“Dismantling these vessels has an inherent risk and you have to take precautions and prepare as thoroughly as you can – and even then, things can and will go wrong – but there is also a lot of pleasure and achievement which outweighs any danger.

“I have been fascinated by it, ever since I was growing up and learning to dive in Fife and starting in the Firth of Forth, and our family – we have three sons and a daughter – are all involved in different parts of the marine industry.

“So the sea has had a pull on all of us and I don’t think that will ever change. When our children were growing up, the talk around the breakfast table was about ships and salvage and going in search of new projects and while I wouldn’t say it was in our DNA, it has become a very important part of all our lives.”

Mr Crawford has survived some brushes with serious injury and incidents which he realises could have had a different outcome.

There was one occasion where he looked on in horror as an “eight hundredweight beam – which was 20 feet long – jumped out of its retaining socket and pinned him against a pile of scrap” by the waist.

Straight away, he knew he was badly injured and the situation was serious, but it was a measure of his phlegmatic nature that he was able to recall everything that happened in the next few hours, despite his agony.

He said: “As we motored to the pier, I could feel my mind wandering and the mists coming in.

“I fought hard to keep conscious, doing my best to assist as they took me up the steps, where I collapsed beneath the crane and the pain started to hit me.

“The next thing I remember is hearing Moya. ‘Alec, Alec, how are you? Oh, Alec’, she said in a breaking voice.

“I could feel her take my hand, but I was unable to see her.

“I must have looked unconscious, because nobody seemed aware that I could hear. Then I recognised the sound of the nurse’s van stopping beside me. Maggie ordered the others to gently get me onto the stretcher and into the vehicle.

“I felt hands gripping me. The pain was almost unbearable, but eventually I could feel myself being carefully lifted into the van and I heard Maggie, a nurse, saying that the ambulance plane would be here soon. So she took me to the airstrip.

“Then the car started. Moya was talking to me as she held my hand. Unconsciousness was passing over me like the clouds passing over the sun. I was struggling to hang on.

“The worst damage was the crushing of my kidneys. I had to sign the consent form for them to be removed before I was taken into the operating theatre.

“Fortunately, the doctors were able to determine only internal damage with the kidneys outwardly intact. It was a question of time to see if they would improve.

“Initially, I was just pleased to be alive, but after the first 10 days when the pain had subsided, I became an unsettled patient, enduring sleepless nights and long days, only broken by Moya’s visits. I longed to get back home to Foula, but Moya was right, as always. I would need time to recover….”

Gradually, Mr Crawford’s health improved, but there were no more deep-sea dives. Yet, either in or out of the water, he has been a trailblazer and master of his own destiny.

The Fifer has always been actively involved in the development of salvage technology, including an environmental system which was used to remove oil from shipwrecks.

This pioneering initiative was highlighted in a Timewatch documentary, The Lost Liner and the Empire’s Gold.

Even now, in his 70s, he is a forward-thinking individual who went to Dundee University to study English, prior to writing his new book. And what is his advice for youngsters who might be interested in entering the salvage business?

He replied: “Put the hours in and realise that there are no short cuts, but enjoy your work at the same time. Accept that not everything will be successful, but it is hugely satisfying to make new discoveries.

“I appreciate that I have been lucky and there weren’t the same amount of regulations 50 years ago that there are nowadays.

“I look at the old pictures of us on boats not wearing life jackets and I feel guilty, but although times have changed, the sea is still a wonderful place.

“And there’s another thing: it is never the same from one day to another, no matter where you happen to be in the world.”

It is there in his voice: the passion of somebody who has truly lived his dream.

Treasure Islands by Alec Crawford will be published by Birlinn Books in September.