My visit to Australia for the Sydney Olympics in 2000 started inauspiciously with the sort of journey which makes you long for the creation of a real-life transporter beam as used in Star Trek.

On a packed flight, en route from Edinburgh to Sydney, via Amsterdam, the last thing you want to happen is have your name read out as part of a list by the cabin crew just 15 minutes before your plane is scheduled to land.

But that is exactly what transpired. We were told that the KLM flight was missing our luggage which had been left behind in The Netherlands.

We were all too weary to make much of a fuss. Thankfully, the events in the next couple of weeks made the missing bags nothing more than a temporary inconvenience.

Olympics to remember

These Games soared into the stratosphere from the outset and made a stellar impression on everybody who was lucky enough to witness them.

If Atlanta four years earlier had been beset by problems with security and blighted by a pipe bombing terrorist incident, while many visitors complained about the exorbitant ticket prices and an excess of Stars-and-Stripes jingoism, there were no similar issues from our hosts Down Under.

Quite the contrary. Nothing was too much trouble for the vast volunteer army who ferried us between the city centre and the Sydney Olympic Park at Homebush on a regular basis. And, as they cranked up their activities on the day of the opening ceremony, it was obvious that something truly special was happening.

The journey to the arena was laced with anticipation and a few butterflies among the Australians, who had waited so long to welcome the world to their party.

Yet, once we were inside the auditorium, the pageantry, sense of occasion and sheer joie de vivre of the throng was contagious. Even those of us who didn’t possess a profound knowledge of Aussie culture and heritage applauded the spectacle which unfolded before our eyes.

It highlighted the beauty of the country, its larrikin nature, cultural impact on the globe, passion for sport and ability to produce champions, but the ceremony didn’t shirk from the often appalling treatment which had been meted out to the land’s indigenous people.

And when one of their number, Cathy Freeman, who subsequently went on to strike gold in the 400m, walked proudly into the spotlight to ignite the Olympic torch, it was one of those “wow” moments when we all cheered and, if truth be told, felt a little lump in our throats.

Thrilling and inspiring

In the next few days, there were myriad moments when the Games thrilled and inspired in equal proportion.

The 17-year-old swimmer Ian Thorpe set a new world record in the 400m freestyle final before helping his compatriots beat the Americans in a dramatic 4 x 100m freestyle final as the festivities began.

He wasn’t the only person to make a real splash in the pool and the schedule passed in a giddy whirl of excitement, featuring the likes of Tom Dolan, Inge de Bruijn, Pieter van den Hoogenband and the ubiquitous Thorpe who became a near-constant presence on our TV screens.

From a more parochial perspective, there was plenty of golden success for Team GB, whether in the velodrome for Jason Queally, the shooting range for Richard Faulds, the boxing ring for Audley Harrison or the sailing circuit with redoubtable Scot Shirley Robertson joining Ben Ainslie and Iain Percy at the top of their medal podiums.

In track and field, Denise Lewis dazzled in the heptathlon and Jonathan Edwards dominated in the triple jump, even as Freeman’s victory in the 400m was the catalyst for a mass outpouring of joy across Australia.

At times, it was difficult to keep up with the blizzard of results, heats, events and emerging news stories at a variety of venues.

But, amidst this frenzy, a couple of wonderful achievements remain etched in my memory, along with the arrival on the Olympic stage of two Scots who later became superstars.

Call him what you will: a man raging against the dying of the light or a stubborn fellow defiantly determined to disprove his critics. It doesn’t really matter, because Steve Redgrave’s performance in Sydney was the stuff of which dreams are made.

At 38, having already won gold medals at the previous four Olympics, he had nothing left to prove about his immensely competitive nature, nerveless temperament and technical expertise.

We already knew how he had whispered “let’s crush some dreams” to his compatriot Matthew Pinsent in advance of grinding his rivals into the dust, but his spirit remained unquenchable. Immediately after surging to gold at the 1996 Games, he famously stated that if anyone found him close to a rowing boat again, they could shoot him.

But here he was, part of the men’s coxless fours with Pinsent, James Cracknell and Tim Foster, proving he was one of the most remarkable performers in Games history.

It was a dramatic race and the British quartet only defeated the Italians by less than half a second in a thrilling denouement.

But afterwards, Redgrave revealed he had told his confreres: “Remember these six minutes for the rest of your lives. Listen to the crowds and take it all in.”

This was despite him being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in 1997, but nothing could get in his way. As he told us: “I decided early on that diabetes was going to live with me, not me live with diabetes.”

Even those who didn’t follow rowing’s ebbs and flows could scarce forbear to cheer.

Freeman’s victory

On the 11th day of the Games, it’s no exaggeration to declare that Australia ground to a halt for a few moments on September 25.

Earlier that morning, I had walked down to King’s Cross and spoken to a cross-section of Olympic visitors and they had all shared the hope that Cathy Freeman would win the 400m.

And, even as we talked, a giant poster of the athlete was emblazoned on a nearby wall, emphasising the burden of expectations which surrounded the 27-year-old.

Was she affected by the publicity? Knocked off her rhythm by the relentless media splurge? Well, if she was, there was no sign of it as she knuckled down to the challenge of boldly going where no Olympic participant had ever gone before.

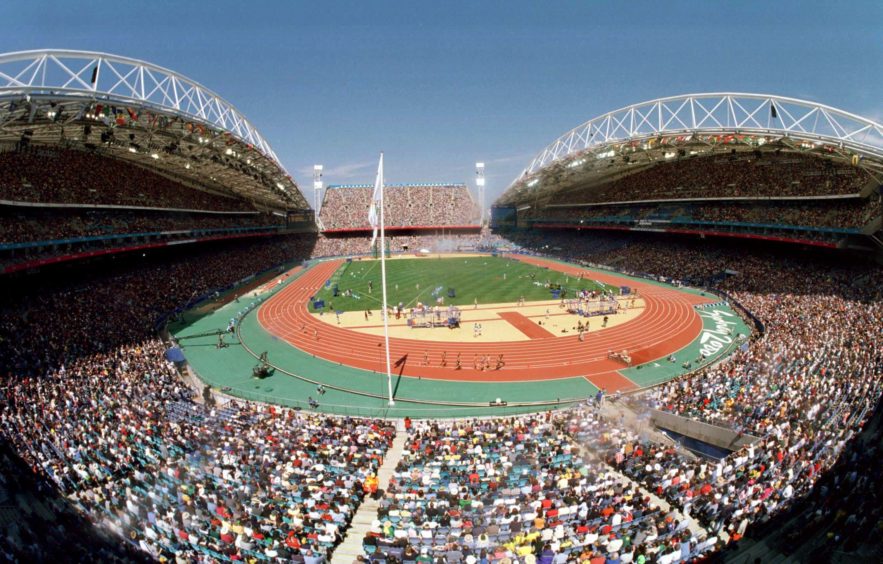

The Olympic Park was bedlam in the build-up: the attendance at the stadium, on a working day, was 112,524 – the largest number of spectators for any sport in Olympic history.

And even those of us who weren’t Australian were increasingly caught up in the fervour once the race commenced.

With hindsight, it wasn’t a classic battle from a strictly sporting perspective – and Freeman later affirmed that she had expected to be tested a bit more – but the lid was virtually lifted off the roof as she powered to her goal in front of Jamaica’s Lorraine Graham and British sprinter Katharine Merry.

At the climax, the noise from the sidelines was deafening. And there were more than a few tears shed when she was subsequently given her cherished gold medal and the Australian anthem reverberated around Homebush. It was spine-tingling.

As a footnote, we discovered that Freeman had become the first competitor in Olympic history to both light the torch and win a gold at the same event.

All the while, she was taking great strides and highlighting how sport can make a difference. And doing so with a modesty and humility which was a credit to her.

A formidable Scots duo

Their greatest Olympic triumphs still lay ahead of them.

But Sydney provided the launch pad for the distinguished Games careers of Sir Chris Hoy and Dame Katherine Grainger.

The duo would eventually join the pantheon of Scotland’s greatest sports personalities, yet they had to settle for a silver lining during their time at the 2000 Olympics.

Hoy, who was just 24, joined with his compatriot Craig MacLean, from Granton-on-Spey and Olympic champion, Queally, in the team sprint event and the trio soon demonstrated their effectiveness as a team.

They had to give second best to an excellent French collective, but this was the start of the remarkable renaissance of British cycling and Hoy (and MacLean) were in the vanguard.

Eventually, Hoy amassed an unprecedented haul of six golds to add to his silver, and he is the most successful British Olympian in the history of the Games.

Katherine Grainger was also 24 when she arrived in Australia and embarked on a Games career which continued until 2016 in Rio.

She appeared in the women’s quadruple sculls event alongside fellow Scot, Gillian Lindsay, and sisters Guin and Miriam Batten at the Sydney International Regatta Centre.

And, although they were beaten by the German quartet, Meike Evers, Manuela Lutze and another sister act, Kerstin and Manja Kowalski, it was just the first stage of her journey.

There were further silvers in Athens in 2004 and Beijing in 2008, but Grainger and her colleague Anna Watkins surged to victory and broke the world record and dominated their rivals at the London Olympics in 2012.

She told the Press and Journal that she had been inspired by watching Steve Redgrave in Sydney – and also Cathy Freeman.

As she said: “Seeing Cathy light the flame and then watching her win the final was electric.

“She handled so much expectation and pressure with grace, style and speed and she did it all on her own terms.”