It’s a story which seems to have come straight from the pages of a John Buchan or Arthur Conan Doyle novel.

After all, who would believe that a habitual criminal could also be a Houdini-style escapologist, a loving family man and a war hero, who possessed enough charisma that songs were composed about his extraordinary life and times?

Gentle Johnny

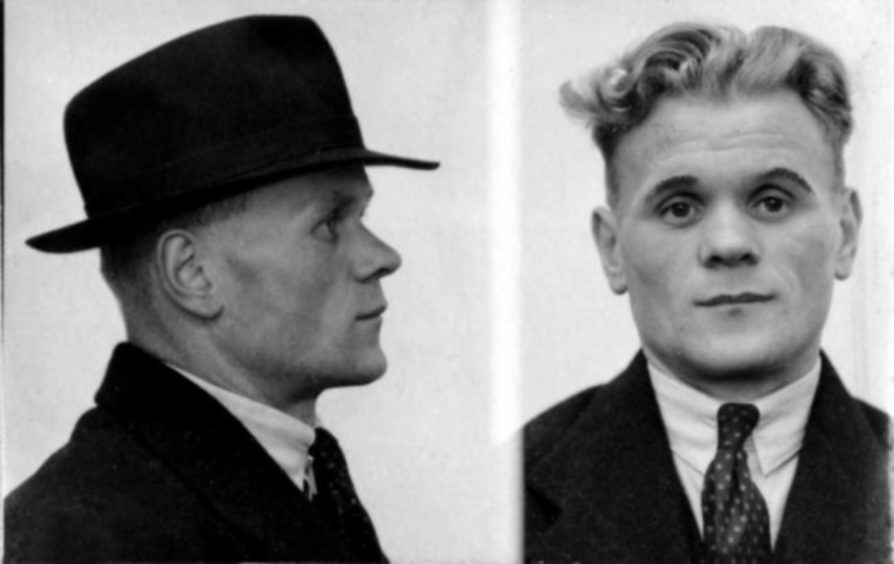

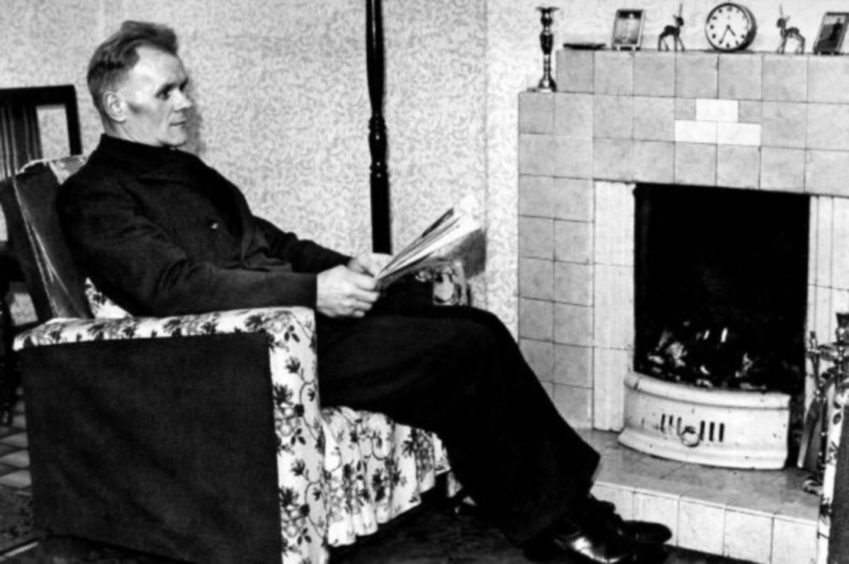

Yet all these descriptions applied to Johnny Ramensky, who was also known as John Ramsay, Gentleman Johnny and Gentle Johnny: the Scottish career criminal who switched roles from con artist to commando during the latter stages of the Second World War.

A popular ditty about him, The Ballad Of Johnny Ramensky, was written by the former Labour MP Norman Buchan and recorded by his brother-in-law Enoch Kent.

And another musical tribute, Let Ramensky Go, was penned by none other than Roddy McMillan, the star of Para Handy.

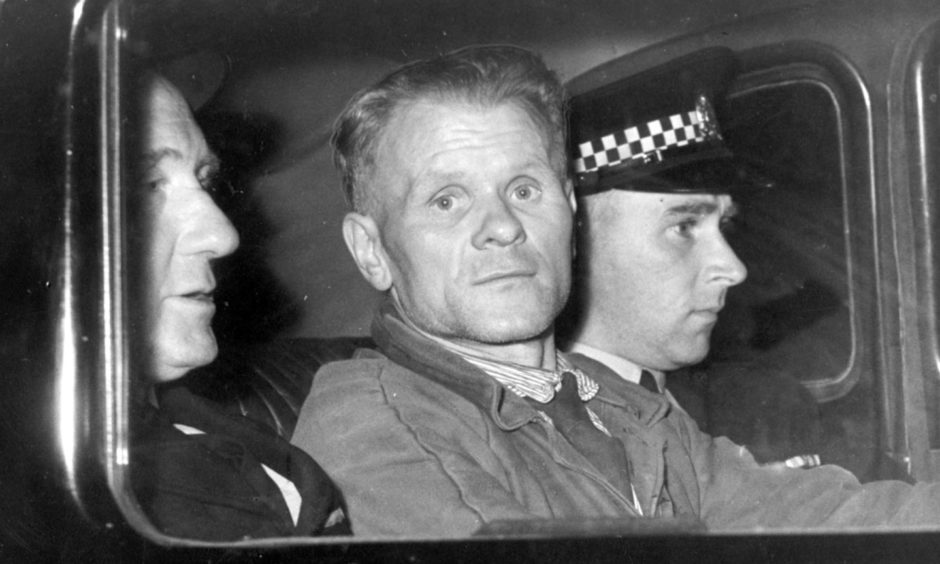

Despite being a serial offender, somebody who was still breaking the law and being incarcerated for his transgressions as a pensioner, Ramensky, born Jonas Ramanauckas at Glenboig, a mining village in North Lanarkshire in 1905, eventually received the nickname Gentle Johnny, even from law officers, because he never used violence when being apprehended by the police.

And although it’s often easy to sentimentalise and sugar-coat the past, there was something about him which meant that even the police who snared him and the courts which he frequented as regularly as others visit their local supermarket, regarded him as somebody who was more interested in eluding an alarm and breaking a code than becoming rich from his forays.

Indeed, the Peterhead Prison Museum, the visitor attraction which is based at the same premises where Ramensky served so many years behind bars, has created a new exhibition space which highlights different aspects of his career.

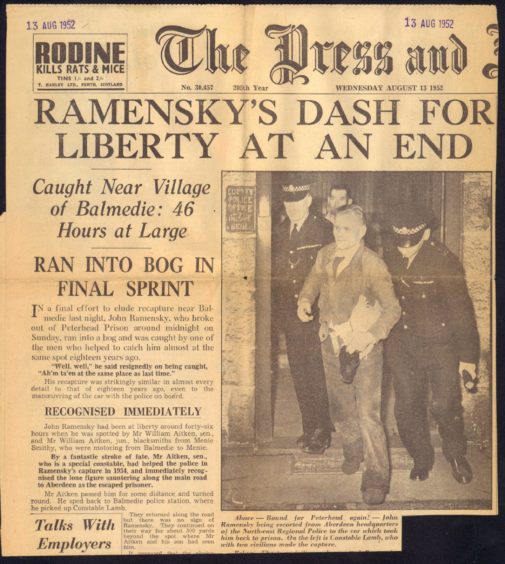

It includes a cell which has been set up in the style of his era, a video about his time in the Blue Toon and a record of his distinguished army service – he was awarded the Military Medal – and even a newspaper account about how two north-east milk delivery boys were instrumental in one of his myriad escapes.

Alex Geddes, the operations manager at the museum, has studied Ramensky’s career, in and out of the clink, and clearly regards him as an extraordinary character.

He said: “There are so many strands to the man it’s almost difficult to know where to start.

“He escaped several times from Peterhead, then he became known as a wartime hero and he established links with locals who served with him in the conflict.

“His two great-grandchildren came up here to see the Scottish escapologist get free from chains, padlock and a locked cell to celebrate Harry Houdini.

“He was given 30 minutes to get out of everything and he did it in just over eight minutes. It’s simply another illustration of how he had this amazing capacity to solve puzzles and mysteries and work out all these intricate details.

“There is a lot of interest in him because he was such a complex individual. And his legend still lives on. We have plenty of visitors who want to hear more about him.

“And I think most of us are fascinated by locked-room mysteries and solving puzzles and Johnny was an expert in these areas.”

Life of crime

Ramensky initially worked down the coal mines, similar to his father who had been a clay miner, and it was there that he became familiar with the uses of dynamite and gelignite.

During the depression of the 1920s after the First World War, his family moved to the Gorbals, in the south side of Glasgow, following the death of his father and the youngster gradually strayed into a life of crime, albeit without any recourse to violence.

Throughout his life, Ramensky demonstrated great strength and gymnastic skill which he employed to begin an unorthodox and illicit career as a burglar and he subsequently developed a talent for safe-cracking and was also known in the underworld as a Peterman.

As Mr Geddes pointed out, he never targeted individuals’ houses but only businesses and he became renowned for avoiding any physical response despite being arrested numerous times, resulting in the nickname “Gentleman (or Gentle) Johnny”.

Occasionally, his eccentricities suggested that he thought he was a modern-day Robin Hood. How else to explain the fact that when Detective Superintendent Robert Colquhoun, one of his old adversaries, was taken ill, Ramensky sent him a message, wishing him a speedy recovery, and suggesting he had been working too hard in pursuing him!

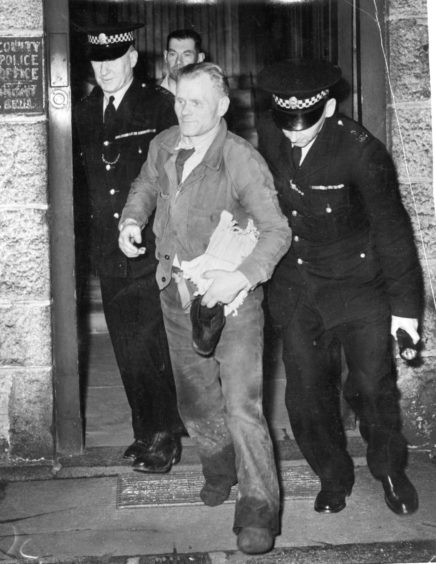

He was the last man to be shackled in a Scottish jail cell, as well as the first to escape from Peterhead Prison, going on to escape and being ultimately recaptured a further four times. He spent more than 40 of his 67 years in prison, but even during these long decades, he campaigned and spoke up for fellow prisoners whom he argued were being mistreated.

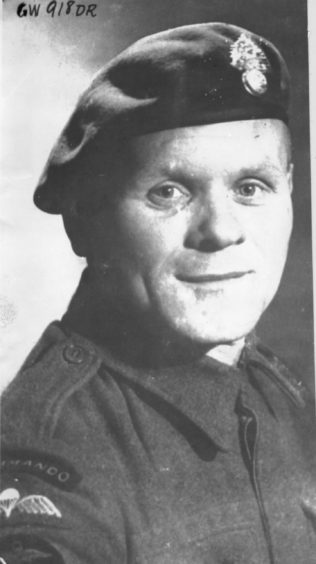

Ramensky was released after serving a sentence in Peterhead Prison in 1943. During his time there, he had written to various officials seeking references to join the army and he made a compelling argument for why he should be recruited.

Eventually, assisted by the intervention of a senior police officer from Aberdeen, he attracted the interest of Robert Laycock who was looking for people with specific skills which could be utilised in commando raiding forces.

As a result, he was enlisted with the Royal Fusiliers in January 1943 and transferred immediately to the Commandos, where he was trained as a soldier whilst also instructing others on the use of explosives: a field in which he had ample expertise.

Thereafter, although being officially enlisted with the Royal Fusiliers, he never actually served with them, spending his entire wartime service with the 30 Commando.

Ramensky, using his safe-blowing skills, performed a number of sabotage missions, and was parachuted behind enemy lines to retrieve documents from Axis headquarters, including Rommel’s headquarters in North Africa and Hermann Goering’s Carinhall in the Schorfheide.

This culminated during the Italian campaign, where 14 embassy strongboxes and safes were opened in the space of just one day as the maestro continued to display his skills.

He remained in the army after the cessation of hostilities as a translator for the allied forces who were repatriating approximately 70,000 Lithuanians from a number of camps in the Lübeck area. Following this diversion, he had a short spell as an officer’s batman before eventually being demobbed in 1946.

Perth Prison

However, despite the plaudits he gained for his nerveless demeanour amid the hostilities, Ramensky did not give up his safe-cracking lifestyle.

He spent most of his time after the war in and out of jail, eventually dying in Perth Royal Infirmary in 1972 after suffering a stroke at Perth Prison.

Even then, in his late 60s, when he might have been collecting his pension and thinking about winding down, he was otherwise engaged serving a one-year sentence after being caught on a shop roof in Ayr. Why was he there? Because, as he admitted, it posed another challenge for him and even though he was rumbled and arrested, he never relinquished his passion for breaking and entering.

One of his friends, Sonny Leitch, another criminal who served in the armed forces, said that Ramensky told him he had stolen a hoard of Nazi loot from the Rome area during the Allied march on Rome in 1944, and that this hoard was kept at the Shepton Mallet military prison in Somerset, and the Royal Navy supply depot at Carfin, Lanarkshire, after the war.

He claimed it contained portraits of Adolf Hitler, Eva Braun, and other prominent Nazis including Goering, Goebbels and Himmler, in addition to a treasure trove of jewellery and gold. Although this was never proved, certain looted items of little monetary value survived him and remain, along with personal items, in a vault in a Glasgow bank.

These are reputed to include banners from Goering’s Carinhall, and Ramensky’s commando beret, his compass and his Commando knife.

During his wartime service, the flamboyant Ramensky – which in itself sounds like a Barnum & Bailey circus act – was also known to have sent various items looted from German and Italian targets to friends and associates in Scotland.

He might have died in 1972 without ever imagining that, nearly half a century later, his feats would be commemorated in one of his old prison patches.

Yet, at this stage, given his surely unique CV, there should be nothing to stop his exploits becoming the stuff of cinema gold.

Further details about all the museum’s activities can be found at https://peterheadprisonmuseum.com/

Johnny Ramensky the movie?

Aberdeen film-maker Lee Hutcheon has been interested in creating a film about Johnny Ramensky for the last 20 years.

The acclaimed movie-maker has so far been thwarted by lack of funding, but he believes the project deserves to be brought to a wider audience.

He said: “I have totally absorbed myself with the many stories of Johnny’s life and his exploits as a master safecracker, escape artist and war hero.

“I have sat with some of his criminal friends who are still alive today and spoken in depth about Johnny’s activities both in and out of prison and his daring missions behind enemy lines.

“To say that Johnny Ramensky was a remarkable man is an understatement, and I feel extremely proud and honoured to be the person who is going to be recreating this emotional story for the world to share via the magical medium of cinema.

“Throughout my extensive research, I have been approached by many people who have encountered Johnny at some point in his colourful life.

“From the families of the old women who brought him in and cared for him during his many escapes, to the families of the policemen who captured Johnny whilst on the run. All of the stories have been as wonderful and as humorous as the next but the one thing that has really amazed me about all of these tales is the fact that none of them had a bad word to say about Johnny at all.

“I find it absolutely amazing that the same man can receive so much admiration and respect from both sides of the law.

“I have listened to so many sceptics and critics saying that the telling of the Ramensky tale would require a huge budget to make it happen.

“I have often smiled when hearing these words knowing there is so much more to the telling of this man’s tale than simply his war years.

“So many people instantly think that Johnny’s story is purely about his Second World War missions. Yes, of course, this does play an important part of our story but there is so much more to this man’s life.

“His childhood growing up in the Gorbals where he first realised his criminal talents is as fascinating and engrossing as any of the other scenes in the film.”

Conversation