It’s an inevitable part of life for all of us, but you could be forgiven for imagining that a book about graveyards and burial places would be short on laughs and levity.

Yet any such preconceptions should be parked at the door of the cemetery when it comes to dealing with Peter Ross, the author of a new work about myriad places of consecrated ground across Britain and Ireland.

The Scottish writer’s previous volumes have gained copious praise from such literary luminaries as Hilary Mantel, Val McDermid, William McIlvanney and Ian Rankin and he has covered the full gamut of life in all its different guises across his homeland.

These include attending the annual Burning of the Clavie in Burghead, interviewing the Naked Rambler in a tent, tracking down a Partick Thistle stalwart nicknamed Harry Bingo, and profiling everybody and everything from a Sikh pipe band to the world championship of crazy golf and the Tayport-based father of modern Scottish photography, Joseph McKenzie.

Mr Ross has now brought an evocative touch to his research into the often compelling past of many burial sites, from the Necropolis in Glasgow to St Finnan’s Isle in the Highlands.

Stan Laurel

And he spoke about some of the discoveries he made, including the grave of the mother of Hollywood legend Stan Laurel which, until recently, lay untended in Cathcart in Glasgow.

A self-confessed tapophile – a lover of graves – he declared how unveiling a rare resting place has the equivalent thrill of a birdwatcher spotting a Blackburnian Warbler.

He said: “A Tomb With A View was twice inspired, if you like: once in childhood, once in adulthood.

“As a small boy, the Old Town Cemetery in Stirling was my playground.

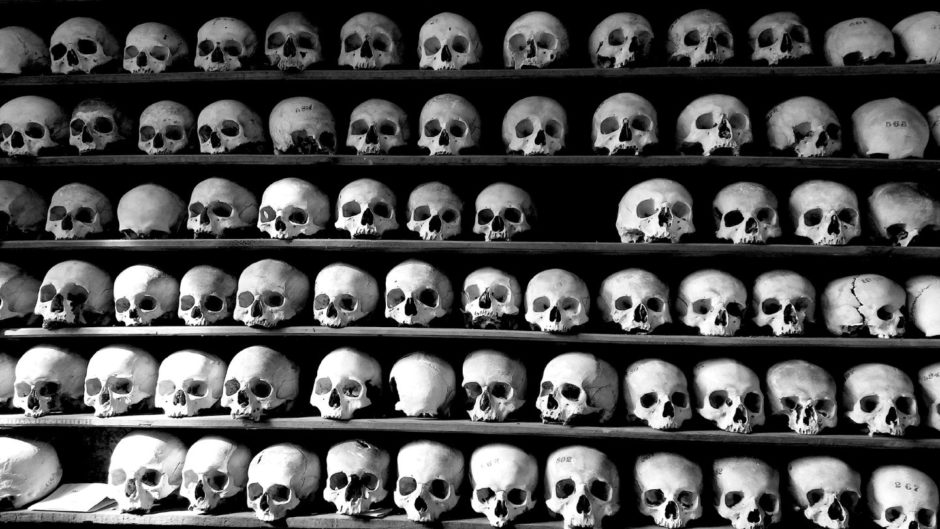

“I would spend whole days, in fact whole summers there, poking my little fingers into the sockets of the stone skulls that adorned the soot-black headstones.

“It’s a wonderfully weird graveyard. The earliest stones are 16th century, I think, and rich in the iconography of death – all those winged hourglasses and skeletons and scythes.

“For a child with an overactive imagination, it was heaven, or the next thing to it.

“Then, a few years ago, I moved to the Southside of Glasgow. My home is right next to Cathcart Cemetery, and I started taking regular walks in there.

“Stan Laurel’s mother, Margaret Jefferson (an actress in the Victorian era prior to her death in 1908) lies in an unmarked grave a little way behind my house.

“One day, while visiting the cemetery, looking for the spot, quite by chance I discovered a small pink gravestone which was half-hidden by ivy. ‘Mark Sheridan, Comedian’ it said, and I went in to confirm that he had died in 1918.

“I had to know more. It turned out that Sheridan was a music hall star from the north-east of England. He is the reason we all know the song, I Do Like To Be Beside The Seaside and his 1909 recording was massively popular. However, the reason he is buried on a hill behind my house, it turns out, is that he took his own life while on tour.

“I was struck and saddened by that story, and it made me think that there must be stories like that connected with graveyards all across Britain.

“That was the acorn from which the book grew. I then spent a year travelling all around the country in the company of the dead. They were good companions.”

Journey to Ireland

Mr Ross was struck by the manner in which death and mourning are regarded across the UK, where some people view it as a chance to celebrate the memory of those who have passed, while others maintain the tradition of wearing black with a heavy heart for the departed.

He believes there is no right or wrong way to grieve, but was struck by the response of many across the water when he journeyed to Ireland and visited sites in the north and the south.

Not that he wasn’t occasionally surprised on many of the trips which he undertook in Scotland, including one memorable foray into the heart of Aberdeenshire.

As he said: “There’s a deep joy in finding an interesting headstone. The churchyard of St Mary’s in Banff has an incredibly cute grim reaper, holding an hourglass and scythe, and wearing not the famous cowl and bony scowl, but a half-smile and what appears to be a tiny pair of pants.

“How this appeared in 1765 goodness only knows, but in the 21st century, it is both deeply sinister and deeply camp; not an easy combination, but one it achieves with aplomb.”

He continued: “The Irish seem to have a much more casual and conversational relationship with their dead than we do; a sort of blethery intimacy.

“From childhood, I have associated visits to cemeteries as quite dutiful and solemn, but the Irish seem to treat it like popping in for a cuppa.

“In Belfast’s City Cemetery, I met a woman sitting on the grave of her mother and sister, leaning back on the stone in the sun, and just chatting away to them.

“In Milltown, the nearby Catholic cemetery, I noticed someone had left a bar of Fry’s Chocolate Cream on the grave of their granny; it was the same shade of blue as the figure of Our Lady which had also been placed on the grave.

“I must say I like that. The idea that these people are gone but not gone, that you can still catch them up with the gossip, is attractive to me.”

Back in his homeland, Mr Ross was witness to several places which made a deep impression on him, not least following a poignant trip to the Highlands.

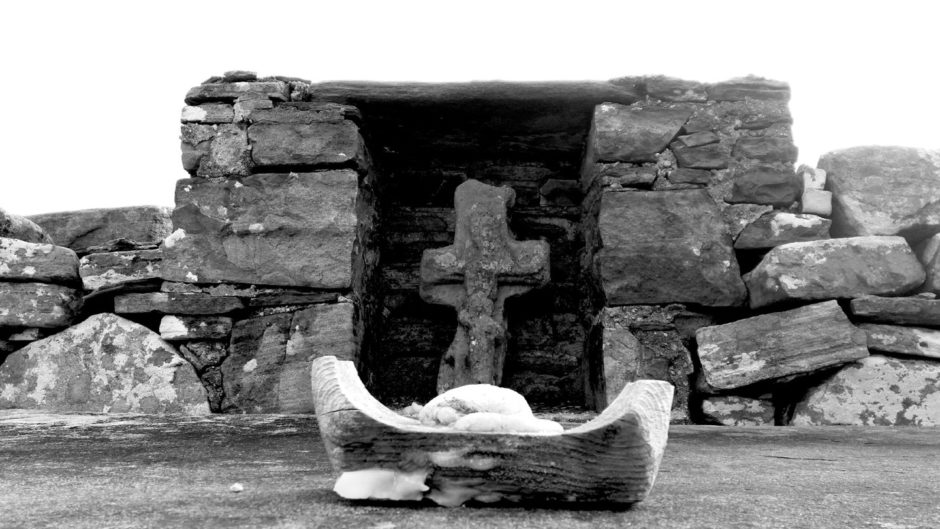

He recalled: “One of the most special places I visited was St Finnan’s Isle. It is known as the Green Isle and it is this tiny island, fringed with scarlet rowans, where local people have buried their dead for centuries.

“I went there with Robert Ross from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission who was on the island to clean and maintain the headstones of a serviceman and woman who had died, respectively, in the First and Second World Wars.

“Some of the graves are ancient, however, and there is a very old ruined church with a stone altar that I found deeply moving.

“The Green Isle, like Iona, is a ‘thin place’, by which I mean that this world and the next seemed as close as two outstretched palms just about to touch.“

Phoebe Hessel

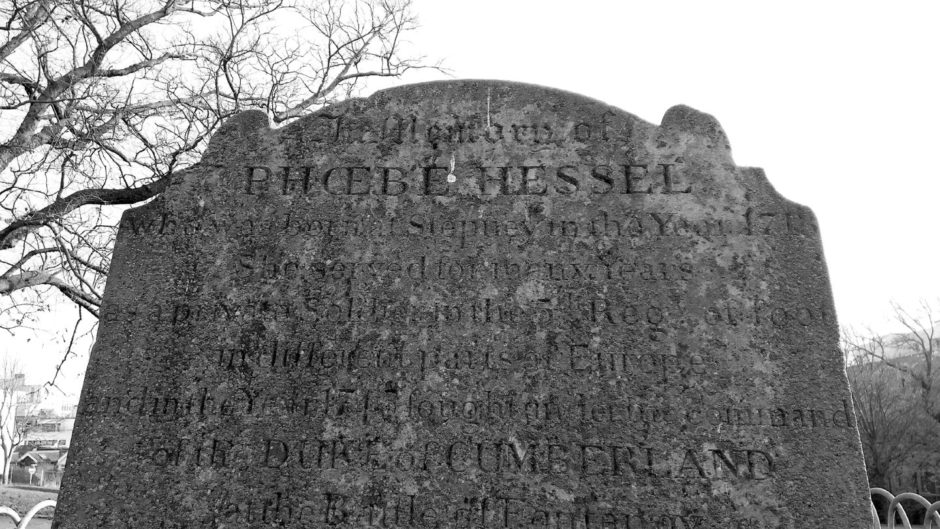

His pursuit of the unconventional has steered him to all points on the compass and he has profiled such remarkable stories as Londoner Phoebe Hessel, who disguised herself as a man to join the British Army in the 18th century, so she could be with her lover Samuel Golding.

This redoubtable woman served as a soldier in the West Indies and Gibraltar and although they were both wounded in the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745, they survived, and were eventually discharged and married, as the prelude to having nine children, eight of whom died in infancy while the sole survivor subsequently perished at sea.

Yet, despite all these privations, Phoebe’s spirit was unquenchable. Indeed, even in her 80s, her evidence was instrumental in securing the conviction and execution of notorious highwayman James Rook.

Mr Ross said: “Her longevity is in itself fascinating. She was a witness to history in a way few others were and there can’t be many who lived in the reigns of five monarchs.

“She fought for King George and was kept in old age by his great-grandson. George IV, as Prince Regent, met her, called her ‘a jolly old fellow’ and gave her a pension of £18 a year, saving her from the workhouse.

“She was invited, as the town’s oldest resident, to be guest of honour at a banquet for the coronation. She had rolled the dice and put herself in a situation – fighting Britain’s wars – where she might have expected an early death.

“Instead, she came up double-sixes and lived a remarkably long life.

“Yet, that too had its sorrows. She survived two husbands and all her children, but she grew blind and lost the use of her legs. Unable to see, unable to walk, unable to forget, she lived on. ‘Other people die’, she said in 1821, aged 108, ‘and I cannot’. The end cane within three months. All her life had lacked was death and now she lacked for nothing.”

Such stories proliferate in Mr Ross’ book and it forms a fitting counterpoint to the more forensic accounts of Written in Bone, the newly-published work by Professor Dame Sue Black.

Mauled by a tiger

Mr Ross has created a dazzlingly-assembled compendium of real people whose lives, deaths and remains leave a enduring impression on the reader even when they are only profiled in miniature.

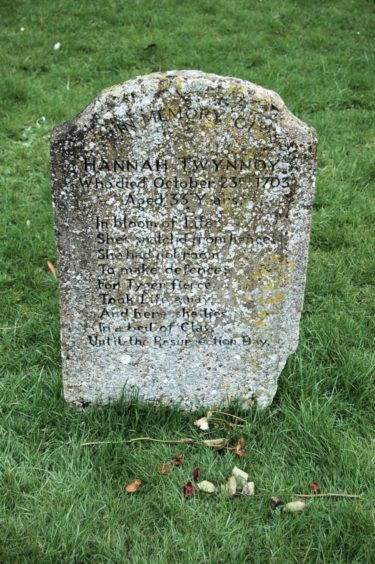

For instance, there is the grave of one Hannah Twynnoy, a maid at the Old White Lion in Wiltshire, who became the first person in England – in 1703 – to be killed by a tiger.

Her epitaph reads: “In bloom of life, She’s snatched from hence, She had not room, To make defence, For Tyger fierce, Took life away, And here she lies, In a bed of clay, Until the Resurrection Day”.

She was just 33, and Mr Ross admitted it must have been an awful tragedy when it happened. But he doesn’t take these stories lightly.

As he said: “It may feel folklorish, but the headstone makes it real. Poor Hannah.

“I always knew that my book about death was going to be a book about life, but it took a storm on All Souls’ Day to teach me it is really a book about love.

“I was visiting a natural burial ground high on a hill in Devon with long views over the River Dart.

“As the wind howled and the rain scoured, I listened to a woman tell me about her late husband who had taken his own life and who was buried beneath one of the grassy mounds.

“It was the privilege of my life to listen to their story, and I realised that love was the great theme of the book.

“That is why I hope, ultimately, that A Tomb With A View isn’t bleak or frightening. I think it is about the best of what it means to be human: the spirit as well as the bones.“

There are an estimated 14,000 cemeteries and churchyards in the UK, of which approximately 3,500 predate the First World War.

These memorials may be fading away and many of the stones are slipping into disrepair, but they tell us how our forebears lived and left the world.

Peter Ross has plenty of material if he ever thinks about writing a sequel.

A Tomb with a View is published this month by Headline.