It was the discovery which changed everything in the north-east of Scotland and transformed the Granite City from an ancient port to the centre of a new energy revolution in Europe.

And, in the years after BP executives told the media they had found abundant reserves of oil in the Forties Field on October 7 1970, a revolution swept through so many different parts of the region as companies began work on erecting a network of giant platforms and creating the infrastructure to extract the precious fuel source from the great blue yonder.

In the space of less than a decade, thousands of people arrived from all over the world, but principally the United States as they realised the vast potential of the Forties Field, which marked the first and largest oil field discovery in the United Kingdom sector.

First steps

Sir Ian Wood has become one of the most prominent figures in his domain, but, as he recalled, there was an element of nervousness even as the first steps were taken in the exploration of the North Sea.

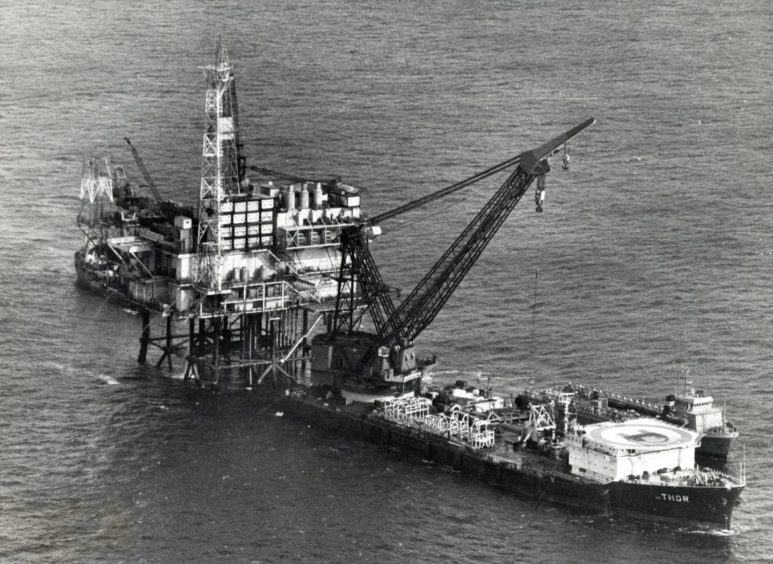

He said: “I remember watching the live film of the Forties platform being taken out to the new installation site and you had a lot of BP senior management standing on a semi-submersible and the camera strayed down to their hands – and, without fail, all of them had their fingers crossed.

“It was a complete unknown what would happen. This was the first time they had taken a structure of that size out and tilted it, so they could get it on the sea bed.

“It was really pioneering and they were innovating and inventing as they went along.”

It wasn’t until September 1975 that the site began producing the precious fuel, as the prelude to being inaugurated by Her Majesty the Queen on November 3, but the white heat of technology had already sprung into action in and out off the North Sea with a series of towering rigs being constructed and dominating the marine landscape even while numerous men and women responded to this modern version of the old Klondyke gold rush.

The phenomenon was unprecedented, but its ramifications are still being felt today. As the Press and Journal discovered from talking to some of those who were present at the birth of the oil boom, they were both exhilarated by their role in a radical new culture and overwhelmed by the rapid retail, commercial and housing expansion – which was accompanied by an incongruous association between bucolic Aberdeen Angus and brash Texas Sam.

Jim Hunter, emeritus professor of history at UHI, was a student in the Granite City in 1970, and then worked on the social impact of oil-related developments in the Highlands and Islands. Like many others, he witnessed at first hand the dramatic progress which was made as scientists, technicians, oil executives and project managers joined forces with Aberdeen City Council and Aberdeenshire Council to map out the best ways to tap into the wells.

He recalled: “There was something of a Wild West feel to it. Some places experienced massive population growth, together with land speculation and much else.

“But, at a personal level, what most impacted on (his wife) Evelyn and I was the runaway nature of house prices. A property would be advertised in the P&J in the morning. That same evening, people – us on occasion – would be queuing up to buy it. But then, the next morning, we would learn it had been sold for way beyond the asking price.

“In Aberdeen, government and local authorities seemed totally bowled over by the sudden availability of jobs and the rest. No thought was given to the longer term – which is why offshore oil has come and gone and left nothing terribly tangible behind it.”

Burger restaurants and cocktail bars emerged along with the familiar sound in the sky of helicopters ferrying men to and from the rigs, en route to the frequently “Foggy Forties”.

The North Sea crews typically worked two weeks on, two weeks off and when they returned to terra firma, they were determined to enjoy themselves. Roulette tables and poker games proved popular with both locals and newcomers in casinos. The night-time economy thrived, as both legal pursuits and illicit activities became commonplace.

But the inevitable population increase required the construction of new schools, traffic networks, housing schemes, medical centres and other amenities and, suddenly, Aberdeen became one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Britain.

Gillian Lowit was only seven years old in 1970, yet she was soon cognisant with the changes which were taking place around her.

She said: “The first I knew of oil was when my dad (the renowned doctor, Ian Lowit) treated a patient who was the daughter of an oil worker from America and he invited us to have a tour of a ship which fascinated me – especially the stories about chopper blades decapitating people on deck!

“I remember the novelty of the American food shop with Lucky Charm cereal and maple syrup and other such exotic goodies. In primary school, I had a friend from Kentucky whose family had come over to work in Scotland and their company rented Forbes Castle on Donside for a time and I was invited to visit – it was very exciting.

“And yet, when I went into teaching and worked in one of the poorest parts of Aberdeen, it began to frustrate me that the city was so split by oil wealth. House prices were ridiculous and everything seemed to cost more which was no good if you weren’t in the industry.

“I saw children living in real poverty and deprivation and yet they were living in one of the richest cities in Europe – the oil capital. It never made sense.”

Riches abounded

Her reservations were shared by others, but their voices were drowned out in the 1970s and for most of the 1980s. As oil production figures exceeded even the most optimistic estimates during the first decade, riches abounded for those who profited most.

One Garthdee resident, Peter Fowlie, put his house in Cults on the market for £50,000 in 1978. His son, Terry, told me how an American gentleman arrived on the doorstep with a suitcase – which contained £60,000 in cash. “My dad was flummoxed. He didn’t know how to react. But eventually, he told the guy that he couldn’t accept an offer in that way.

“So the chap scratched his head for a few seconds, then told him: ‘That’s okay mister, I can make it £70,000 tomorrow morning if you like’. It was totally crazy.”

Not everybody was dazzled by dollar signs or enamoured of the fashion in which oil gradually took a grip on the area. But many of the traditional industries which had bolstered the north-east economy were showing signs of decline.

Jimmy Milne, the chairman and managing director of Balmoral Group, the organisation which is celebrating its 40th birthday this year, was among the more pragmatic individuals who carefully laid the foundations for his company’s success.

He said: “I was born in 1940 and, of course, can well remember when the oil industry moved into town. I witnessed the city move from such traditional industries as quarrying, shipbuilding, paper making, fishing and farming to become an internationally recognised centre of excellence for the offshore energy sector.

“Many great people and organisations have come and gone during these 50 years – too many to mention, actually. But one thing is for sure: the north-east has benefited enormously from this slice of geographical and geological good fortune.

“Standards of living have improved enormously for thousands of people. I appreciate that not everybody in the region is directly involved with the industry, but most sectors have benefited from the spin-offs which have been associated with it.

“The city and its residents have shown that they can adapt to change, seize opportunities that present themselves and bring substantial benefits for those who are willing to work hard – and we have an outstanding work ethic in this part of the world.

“We have been fortunate, but we have also made our own good fortune by being flexible, adaptable and inventive and I cannot see that changing.”

None the less, it was the minority of people who flourished and that disparity generated problems which created a social divide. At several stages on either side of the millennium, there was discussion about introducing an Aberdeen Weighting Allowance – such as exists in London – to help attract key workers, including teachers, nurses and emergency service personnel, to relocate from other parts of Scotland to the city.

Trouble brewing

But some of the problems were detected early on by the likes of historian and former Aberdeen councillor John Corall, who could anticipate trouble brewing even four decades ago.

He said: “Pre-oil, we had town gas manufactured down at the beach in large coking ovens and it was stored in the huge gasometer adjacent to Pittodrie.

“The oil boom brought in natural gas and so every gas appliance had to be converted to run on this new fuel.

“The influx of rednecks from the southern states of America was a source of bemusement to many people, because until then, Stetsons were not normal head attire for Aberdonians.

“They also had plenty of money to spend, so many locals looked on enviously and tried to get jobs offshore. Many managed it and this did create a situation where you had the ‘nouveau riche’ and less pushy locals, part of it envy and part of it ‘fa dis he think he is!’

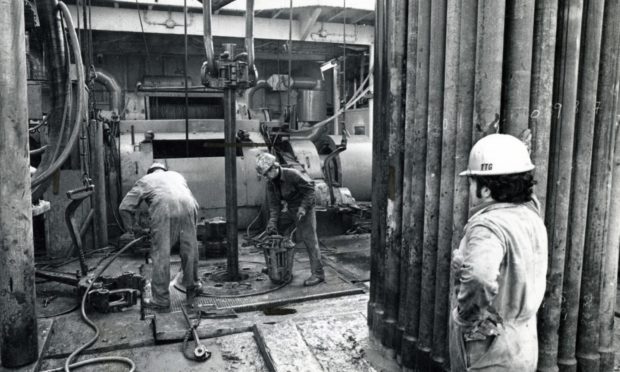

“It became apparent early on that the Gulf of Mexico and the wild deep grey North Sea had much less in common than initially thought.

“But increased wealth followed relatively quickly as more and more indigenous people went to work offshore on the rigs. Health and Safety was not a big feature then and I remember Sandy Brown (the owner of the Blue Lamp pub, who died earlier this year) and I going out for a Sunday afternoon jaunt in a helicopter, landing on two barges and five platforms, as there happened to be a couple of spare seats on that flight.

“Boom and bust was, and still is, a feature of the oil business and many folk just fled the area when they became unable to pay their mortgages.

“There were alarming house price rises which were the consequence of the new wealth of the oilies. And those who didn’t work in the sector were severely disadvantaged – a situation which has remained to this day.

“So yes, the oil has transformed Aberdeen and many individuals associated with the business have benefited from the developments, but collectively, the town is bereft of any lasting statements, apart from the monument in Hazlehead Park, which commemorates the deaths of 167 men in the Piper Alpha disaster.”

That tragedy was the first reminder that an often reckless disregard for safety would wreak a dreadful toll on those employed in the North Sea.

However, when the oil began pouring into the barrels and new fields were unearthed, it was widely regarded as an economic miracle.

Few at the outset questioned how long it would last, let alone contemplate devising strategies to prepare for a day when the wells ran dry.

However, the Aberdeen Children of the 1950s project has provided an illustration of how the oil and gas boom in the 1970s and 1980s enhanced many people’s lives.

The venture followed 12,150 state school children in the Granite City from 1962 onwards and collected information from childhood, including school tests, through to adulthood, using such initiatives as questionnaires about health.

Researchers from around the world have employed the findings to investigate questions about how different life experiences and circumstances can affect people’s health, wealth and happiness.

Two of those involved in the Aberdeen University analysis, Marjorie Johnston and Krzys Adamczyk, unveiled some of the lessons of the study.

Job security

They revealed that around 75% of the 7,183 members who completed a postal questionnaire in 2001 – who are now aged between 63 and 69 – were still resident in the Grampian region of Scotland, indicating that many people enjoyed job security in and around the offshore sector, allowing them to remain close to their roots.

The research also highlighted that around 10,000 of the original participants are still alive with average life expectancy having risen by almost a decade in the north-east since the 1950s.

Mr Adamczyk said: “The oil boom made a significant difference to the lives of so many members of the Aberdeen children’s group.

“It happened just as many of them were leaving school or progressing into further education and there were so many more opportunities for that generation.

“In the 1970s, a lot of American expertise was required after the discovery of oil in the North Sea, but many Aberdonians who started out in blue-collar jobs graduated into white-collar managerial positions and management roles in the 1980s and 1990s.

“That transformed the jobs situation in Aberdeen and the surrounding areas.

“Usually, when you look at what your classmates have done, you’ll find many of them have had to travel elsewhere to find the work they want.

“But the fact that so many state school children from half a century ago are still living in this area is remarkable.”

They were the winners at the forefront of this modern industrial revolution. But even the splurge of new money in the region didn’t come without its own problems.

Susan Sutherland arrived in Aberdeen in the late 1970s after getting married and beginning work with an insurance company in the city. She and her friends were amazed at the extravagance which surrounded many oil company events where they discovered that “the drinks were free and people just drank as much as they possibly could”.

And yet, as the woman who is now the Rev Susan Sutherland at Mastrick Parish Church gradually learned, this lavish lifestyle didn’t automatically bring happiness or stability.

She said: “I asked a parishioner what oil had brought to the community. She replied that oil workers bought their council houses in Mastrick and did them up with new fireplaces and built walls around the properties to make them look different.

“Then they sold their houses and moved to Bridge of Don or Westhill to better themselves.

“However, she also said she had to feed her next-door neighbours’ three kids. And the reason for this…well, when the husband was offshore, the mother was never out of the pub.

“So you can see that money brought its own problems.”