Stewart Milne vividly remembers the impact which the discovery of the Forties Field in the North Sea had on the region when he and his generation grew up.

Nowadays, he might be better known as the former chairman of Aberdeen FC, and the name behind one of the country’s leading housebuilding companies.

Mr Milne was just 20 when BP’s executives told the media they had struck oil, but the news was the catalyst for a remarkable transformation in his fortunes.

Regret

Yet, even though he capitalised on the expansion which happened across Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire in the aftermath of the energy revolution, he has told the Press and Journal about his regret that more wasn’t done to spread the wealth equally.

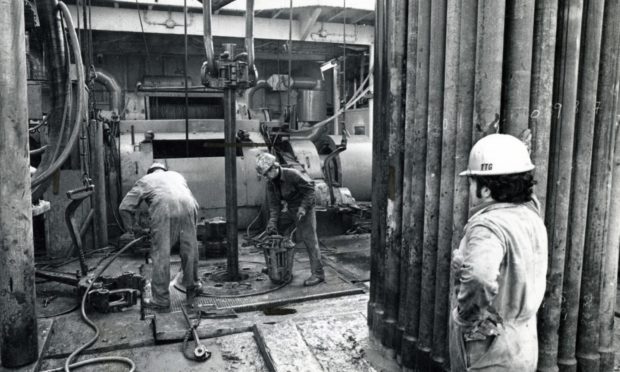

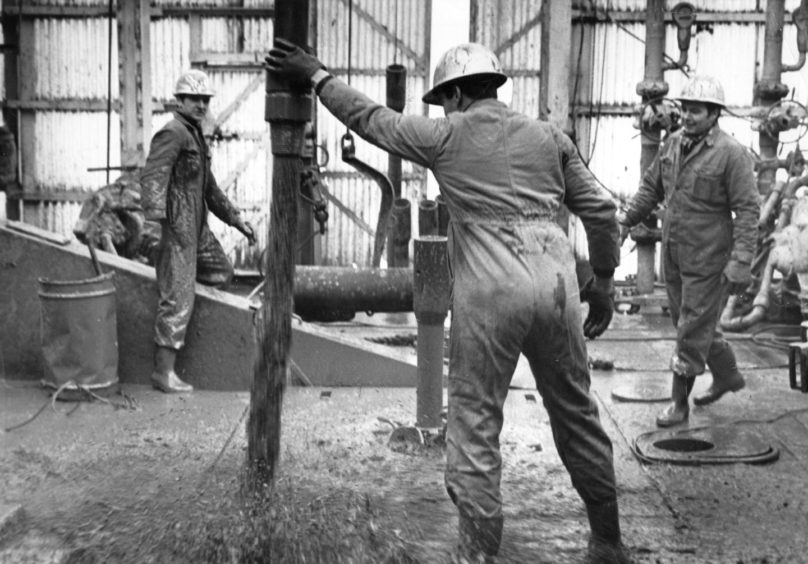

He said: “My first memories of the oil industry arriving in Aberdeen were when I was serving my time as an apprentice electrician.

“At this time, the city council were encouraging kitchen/bathroom conversions in tenement properties, and were making grants available for this.

“This was largely driven by need, but also by the increase in wealth as a direct result of the oil industry. The opportunity this presented was what first sparked the idea of setting up my own business.

“With an influx of Americans into the city and more money around, there was a real drive to deliver new housing. The one memory that stands out and perhaps changed the perspective towards development in Aberdeen was when an auction was held in the Station Hotel for the first acres of land opening up in Westhill.

“Up until then, land in the region was selling for between £4,000 and £7,000 per acre. The high interest in and demand at Westhill saw prices shift to around £20,000 per acre. Today, we’re looking at anything between £750,000 and £1m for an acre! Westhill and the Bridge of Don, which was also developing at this time, were hot spots for homes for workers in the fledgling oil industry.

“Many of my fellow apprentices were attracted to working offshore, lured by the money and the potential of working two-on, two-off. I wasn’t tempted because I was concentrating on serving my time and carrying out ‘homers’. The appeal of being my own boss was more attractive to me.

“To begin with, many of the Americans who had arrived in Aberdeen saw it as a short-term thing and moved into rented accommodation and I was kept busy carrying out jobs for them in these properties. I remember being surprised by the number of power sockets they wanted. Where typically a room had two sockets, the Americans wanted four or five!

“However, in a short period of time, when it became clear that they were going to be here for longer, they started buying their own properties. With more wealth and more people buying homes, the property market in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire was suddenly booming. But the city’s amenities struggled to keep pace.

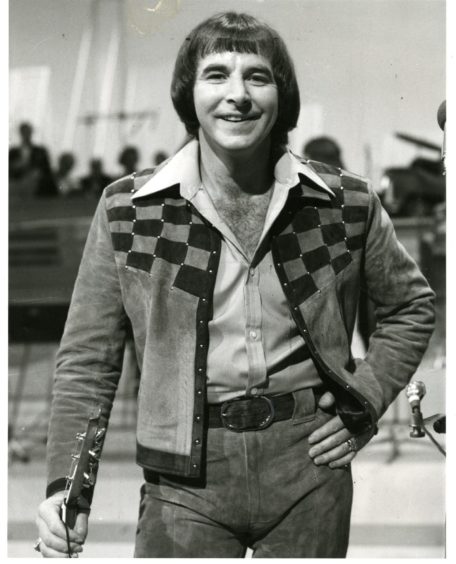

“It was a great time for the hotels, most of which were also the favoured drinking holes and centres of entertainment, such as Sydney Devine, who was a regular at the Cloverleaf. The other hotels which became hotspots during this time were the Imperial and Ricky Simpson’s hotel the Craighaar.

“There is no doubt that these early days of oil accelerated Aberdeen’s development and created a more enterprising culture which, although maybe always inherent in the region and its people, was taken to a new level.

“Since those heady early days, we’ve seen many ups and downs due to the cyclical nature of this commodity-driven industry but this is what has made us more innovative and resilient.

“The industry has undoubtedly put us on the map globally in a way that no other industry could have done. There are however some regrets – that we didn’t capitalise on it enough at the beginning as a city and make sure that the wealth it generated was invested in our sustainable, long-term future.

“Being more visionary and forward-thinking back then may have helped secure more investment in our communities and a more equitable distribution of the wealth which oil has generated across our communities.”

His beloved Dons obviously achieved a series of memorable triumphs in the 1980s as the city and the club thrived, with victory in the European Cup-Winners Cup over Real Madrid highlighting the quality of the team under Alex Ferguson in 1983.

Aberdeen FC

However, lifelong fan and Bafta-winning film director, Jon S Baird, wasn’t alone in wondering about the lack of investment in the club from the energy sector.

Mr Baird has lived in London for the last 20-plus years, but still returns to the north-east on a regular basis. As a youngster, he relished the rise of the oil and gas sector and revelled in the achievements of Ferguson’s fabled squad.

Yet he still has questions about what he perceives as a lack of joined-up thinking with old industries facing increasing problems in the modern world.

He added: “When I was growing up, places like Peterhead and Fraserburgh were really booming, mainly due to the fishing industry, so the economic gap between people was far less than it is nowadays.

“But I’m delighted to see the Aberdeen bypass open and transport links improving at last, and it has made a big difference because the Banff and Buchan area previously felt like a forgotten corner of the country.

“The other obvious difference is in the fortune of my beloved Dons. The club had tremendous success, in Scotland and in Europe, in the early 1980s and I think that we should have built on that more at the time.

“In fact, it always seemed strange to me that some of the large oil companies, firms who had done so well from the area, did not invest more in our local club.”

In Norway, an oil fund was created to ensure that the boom would not be a short-term phenomenon. But while some politicians in the 1970s and 1980s suggested such a strategy should be implemented in Scotland – and the efficacy of the slogan “It’s Scotland’s Oil” was one of the reasons why the SNP enjoyed increased electoral success at Westminster in 1974 – there was no similar scheme adopted to store up financial reserves for future generations.

Or at least, not on the mainland. Elsewhere, though, developments were closely monitored by historian and writer, Jim Hunter, the emeritus professor of history at UHI.

He said: “One aspect of those times that has stayed with me – and which connects with this month’s story of Shetland Council seeking autonomy from the rest of Scotland – is the comparative success of Shetland in dealing with the oil bonanza.

“Shetland pressed for and got the Act which gave the council powers of a kind which weren’t available to other local authorities.

“Out of that and out of their successful negotiations with the oil majors and other companies in relation to the Sullom Voe terminal came the Shetland Oil Fund – which has left legacies in the shape of leisure centres, a superb library and archive and much else.

“In much of the rest of Scotland, including Aberdeen, government and local authorities seemed totally bowled over by the sudden availability of jobs and all the rest. No thought was given to the longer term or to securing Shetland-equivalent benefits.

“That is why offshore oil has come and gone and left nothing terribly tangible behind it. Why is Aberdeen bereft of the superb community assets that, in a better ordered world, you might have expected the oil majors to fund and endow?

“Why does Union Street seem a much less attractive thoroughfare now than it did in the pre-oil days when, arguably, the opposite should be the case? In part, I reckon it’s because the rest of us lacked what Shetland had in spades – the realisation that the oil companies needed Scotland at least as much as Scotland needed them.

“We never really grasped this. The tax revenues were treated as income by successive Westminster governments. None of them were stashed away in the equivalent of a Norwegian wealth fund. Only in Shetland was there some attempt to look to the long term.

“The famous John McGrath theatrical production The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil was good on this subject at the time. In the play, the oilman, Texas Jim sings:

“Take your oil rigs by the score, Drill a little well just a little off-shore, Pipe that oil in from the sea, Pipe those profits – home to me.”

Profit and loss

However, the transformation of the north east hasn’t simply been a tale of profit and loss. In recent years, links between energy companies and charity organisations have been pivotal in the creation of all manner of entrepreneurial initiatives.

Many companies, ranging from Wood Group to BP and Balmoral have actively encouraged the creation of philanthropic ventures and groundbreaking schemes which have bolstered – and continue to boost – the NHS, the arts, sport and culture.

They also supported an eclectic range of events including the Aberdeen International Youth Festival which attracted thousands of youngsters to the city from all over the world.

And business figures in the mould of Jimmy Milne, the chairman and managing director of Balmoral Group, devised bold new ideas such as Courage on the Catwalk and Brave to raise money for Friends of ANCHOR and offer people with cancer the opportunity to strut their stuff in the spotlight.

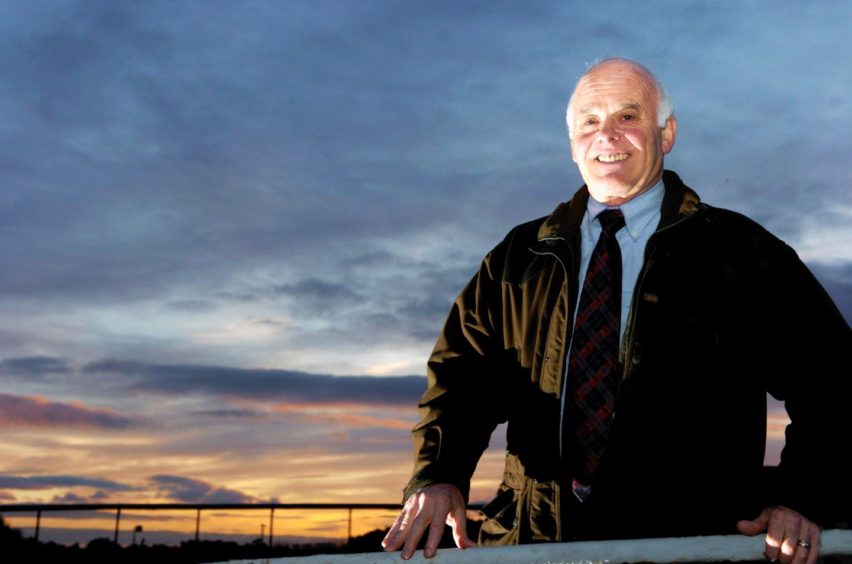

Mr Milne is proud of the charitable spirit which exists in his home city and refuses to be downcast by the decline in oil and gas since the halcyon days.

He told the Press and Journal: “Standards of living have improved enormously for thousands of people and most sectors have benefited from the spin-offs associated with oil.

“We are, of course, going through another transitional phase at the moment with the move towards more sustainable, greener energy resources.

“Aberdeen is already showing its capabilities on this front, building on its reputation for innovation by driving the offshore wind sector forward quicker than anyone thought possible.

“We have been fortunate, but we have also made our own good fortune by being flexible, adaptable and inventive and I can’t see that changing.

“Aberdeen is recognised as a global hotbed of subsea expertise and it is good news for the city that so many people, once they are here, are not inclined to leave.”

There will probably always be a sense of what might have been, while a number of fatal helicopter crashes – which claimed the lives of 43 people at Sumburgh in 1986, six when a craft struck the Brent Spar oil storage platform in 1990, 11 off the Cormorant Alpha rig in 1992, 16 off Peterhead in 2009 and four a few miles from Sumburgh in 2013 – demonstrated the risks involved for workers and pilots flying to and from oil installations.

But while the oil revolution has petered out in recent years, and almost ground to a halt during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, there are no shortage of people who have lived through the whole energy boom and believe so many issues were never properly addressed.

Lack of investment

Kenny Anderson, the previous chairman of Clan Cancer Support, was just 12 and growing up in Glenlivet in 1970, but when he began working as an apprentice quantity surveyor in Aberdeen in 1977 and supplemented his income as a part-time barman in the Royal Darroch – a popular haunt for workers in the industry – he was struck as much by the lack of infrastructure and investment in the Granite City as the more ostentatious flaunting of money in the bars, restaurants and nightspots which have now disappeared.

He said: “Helicopter traffic grew and, in every boom cycle, the industrial estates expanded, but the city centre didn’t seem to benefit to any great extent.

“The redevelopment of the airport missed the opportunity to incorporate a rail link and, while the harbour thrived, there was little room for fishing or other maritime activities other than those related to oil.

“Aberdeen certainly became more cosmopolitan with international schools and the rapid growth of two universities, but culturally, chances were squandered.

“The downturn of 1986 occurred again in 1998 and 2008 with the current slump made far worse by Covid. It does make one look wistfully at what Norway has achieved.

“Has the discovery of oil and gas been good for Aberdeen, Scotland and the UK? Yes.

“But has the discovery of oil and gas been as good as it could have been for Aberdeen and Scotland? No!”