John Wright takes a look at some of the crimes committed by local residents that resulted in them being ‘transported’ to another world

The north and north-east of Scotland provided its fair share of 136,000 men and 25,000 women transported to Australia from 1788 when the First Fleet arrived Down Under, where women were assigned as servants and men often sent farming, such as Aberdeen’s Thomas Brown, whose crime, committed in Melcombe Regis, Dorset, was that he “falsely pretended to be a captain of a ship”.

The case of Alexander King, 21, was typically odd for colonial days. “His first offence in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) while a constable in Hobart was ‘misconduct in wilfully shooting a dog, the property of Mr Hickson, and threatening to put him in the watch-house’ for which he got four months’ hard labour and was dismissed from the police force,” Phillip Hilton and Susan Hood wrote in Caught in the Act: Unusual Offences of Port Arthur Convicts.

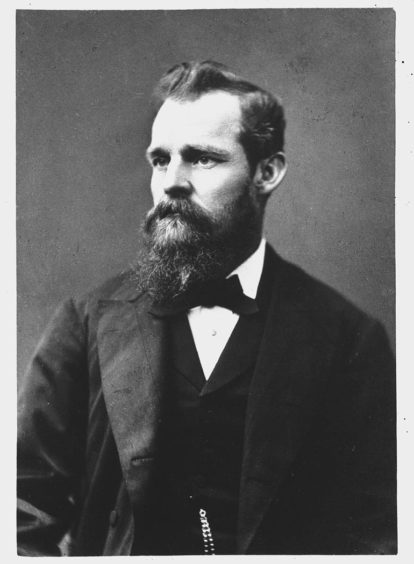

King, an Aberdeen tailor, told the judge at the Aberdeen Court of Justiciary in 1837: “I have been engaged in stealing nearly all my life,” (he was 14) when sentenced to 17 years after housebreaking and stealing money from a pocket book, and, curiously, was made a cop almost the moment he arrived in Australia.

Thief Janet Bisset sailed to Tasmania on the Harmony in 1828, her accuser being Joseph Craig, manager of the manufactory of Alexander Hadden and Sons, woollen manufacturers in the Green of Aberdeen. Her court record stated that “nine empty bobbins belonging to the said company were found concealed under the bedding or bedclothes in the said Janet Bisset’s bed”.

“Anne Balfour, 25, travelled with her nine-month-old baby, leaving her four other children at home in Aberdeen,” the Edinburgh Evening News wrote. She had worked as a country servant and had skills in milking, making butter and cooking and was transported after stealing money given to her by a man to buy whisky. Isabella Watt, 25, was transported with her eight-year-old child after being convicted of theft and robbery, both women banished in 1835. Watt’s “brothers, James and John, were already in Hobart when she arrived. Her sister, Hannah, followed in 1838 after being convicted of theft”. Some committed crimes so they could be together.

The article quoted Aberdeen researcher Lesley Dunbar, who followed the fortunes of five Aberdeen women, all “convicted in the High Court in Aberdeen in April 1835 and three of them came from the same street. As far as is known, Isabella Watt, Elspet Leslie, 62, Ann Balfour, Margaret Millar, 40, and Isabell Cruickshank never saw Scotland again”. They sailed on the convict ship, Hector, on which they “were fed and looked after. Clothes were kept clean, water and limes supplied and time spent on the upper deck, weather permitting”.

Sounds idyllic? Leslie had rheumatism and “after arriving in Hobart, spent 130 days in hospital and was described as ‘incapable’”, and the ship’s surgeon, Morgan Price, wrote about Watt in his journal: “This woman has been greatly addicted to drinking and there is evident a considerable derangement of the system – yellowness of the skin and of the Tunica conjunctiva – disagreeable taste in the mouth and every symptom of marked interception of excretion of bile – constipated bowels.”

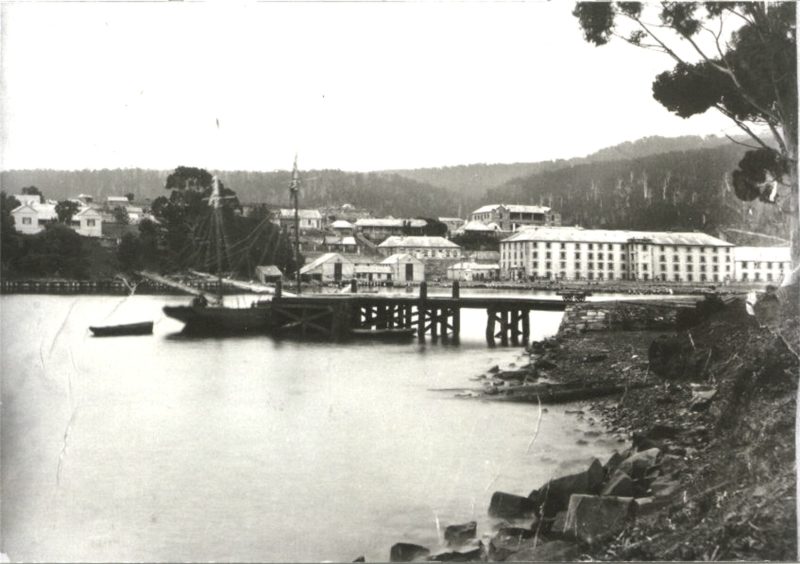

“On arrival in Hobart, all five women were sent to the Cascades Female Factory,” Dunbar said, “the Aberdeen women all sent to work in the homes of wealthy settlers.” Millar, from the Printfield area of Aberdeen, was transported “after stealing one shilling and sixpence when drunk and was returned to Cascades after stealing from the Governor’s House, her sentence extended by two years”.

Twenty-three-year-old Ninian Melville sailed through Sydney Heads from Aberdeen in 1833 after being sentenced to seven years’ transportation (the usual term) at the Perth Court of Justiciary for stealing clothes. In Sydney, he set up as a cabinet maker in the 1840s, as did his son Ninian Junior who, like his dad, got interested in politics and the pair badgered crowds from soap boxes in Sydney’s Domain, Junior later becoming a prominent Sydney politician and undertaker.

It was often hard to keep up with marriages. Inverness-shire-born Mary Lindsay, 20, was tried in Aberdeen and transported to Tasmania with her three-year-old son, her husband Isaac Williamson arriving there a month later. Whether they reunited or not is unknown, but her convict record states that in 1844 “Mary applied for permission to marry William Higgs. After Higgs’ death Mary married William Pearce in 1864” and, her record not clarifying whether he was alive or not, in 1870 she married William Hookey”.

Malcolm McLeod, from the village of Bayble in Point on the Isle of Lewis, escaped hanging and was transported to New South Wales for life in 1839 for murdering his wife Henrietta, one declaration stating that initially they “lived very happily, had three sons, but within the last three years they did not live so happily, which arose in consequence of a certain coolness on her part, she not appearing to be so attached to him as formerly”. The Inverness Circuit Court of Judiciary judge certainly thought insanity rather than plain nastiness accounted for the fact that “McLeod did wickedly and feloniously seize her by the face and did violently compress her mouth and nostrils so as to prevent her from breathing and did throw her down and…” the typically gruesome trial testimony details went on.

Shetland-born James Mathewson, 48, was transported to Tasmania in 1850 after being convicted for “the theft of six gallons of oil from the docks at Freefield, a cow hide and a cask or punchion of whale oil”. He was gaoled initially in Lerwick’s Fort Charlotte before sailing for the sun.

Sometimes descendants go looking for the truth about their convict ancestors, such as a relative of William Spence, banished for 10 years in 1866 by the Edinburgh High Court of Justiciary. “He was born in the parish of Holm in 1818. His parents, William Spence and Mary Ann Gurthrie, farmed there at Biggins and Craebreck. The journal of James Robertson, Sheriff-Substitute of Orkney, identified that William Spence set up business as a merchant with his partner Robert Tulloch in Kirkwall in 1850.

“In the 1861 census, William Spence is living at 11 Broad Street with his wife, his seven children, an apprentice and two servants. He appears to be a successful draper and general merchant. However, in the 1871 census his family are living in a slum in Edinburgh.” The relative gets confused but finds an 1864 article in The Caledonian Mercury quoting The Orkney Herald: “EXTENSIVE FORGERIES BY A KIRKWALL MERCHANT” and asks, “Could this be my great-great-grandfather?

“Much excitement was caused in the community at the beginning of last week by the rumour that Mr Wm. Spence, a well-known merchant in Kirkwall, had been imprisoned for extensive forgeries. This rumour, which many were unwilling to believe, turned out, unfortunately, to be only too true; and as the intelligence spread through the town it awakened mingled consternation and astonishment, since Mr Spence, from his position as an elder in the United Presbyterian Church, and from the apparent interest he took in religious matters, had previously enjoyed the reputation of being an honest and consistent man.”

The anonymous descendant dug further, finding out that his future family convict “had been obtaining his shop stock on credit from Anderson and Co., Glasgow, and they had refused him any further credit… then forged the signatures of James Williamson, grain merchant, Kirkwall, and Andrew Muir, farmer, Craebreck, for £300 credit… and started to forge signatures on a series of promissory notes,” all up £2,580 (£330,000 today).” He was aboard the Belgravia, arriving in Western Australia in July 1866, only to die of dysentery the following March in the year transportation was abolished.

Military guard Adam Carmichael, 23, was sentenced to 14 years at the Aberdeen Court of Justiciary for stealing from an Aberdeen shop “20 cheeses, gin, tea, candles, oranges, tobacco, spirits and two pairs of worsted stockings after 20 witnesses gave evidence against him”, Marjorie Tipping wrote in Convicts Unbound: The Story of the (HMS) Calcutta Convicts and Their Settlement in Australia.

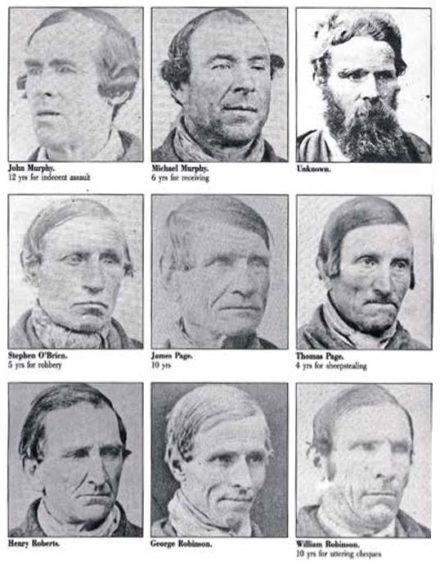

Re-offenders and serious criminals in Tasmania were sent to the Port Arthur Penitentiary on the island’s south-eastern peninsula that was separated by a narrow neck of land guarded by vicious dogs. “Crimes” here varied from trivial to ridiculous, Hilton and Hood citing John Glanville committing 55 offences, including “having turnips improperly”, other miscellaneous offences being “having lollipops in his possession; setting fire to his bedding; threatening to split the overseer’s skull with his spade; wilfully breaking his wooden leg; apprehending Godfrey Moore and biting his nose off; groaning at the lieutenant-governor”, and one woman for “concealing a man under her bed”.

Best of all was “Billy” Hunt, his crime – absconding. Nothing unusual about that, except Billy was “dressed as a kangaroo at the time and was attempting to hop to freedom”.

This is just a glimpse into the weird and wonderful world of the justice system in the 18th and 19th Centuries. No matter how flawed our current system may be, it is clear to see it has improved quite a lot since the days of shipping convicts to the other side of the world.