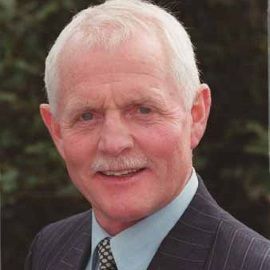

Gordon Bathgate can barely recall a time when he wasn’t in thrall to the radio and marvelling at all the different sounds which came out of a magic box in his living room when he was growing up in the north-east of Scotland.

A lot of snap, crackle and pop music has come and gone since these early days, but he is still Radio Ga Ga about an invention which has shaped all our lives and is celebrating its centenary in 2020.

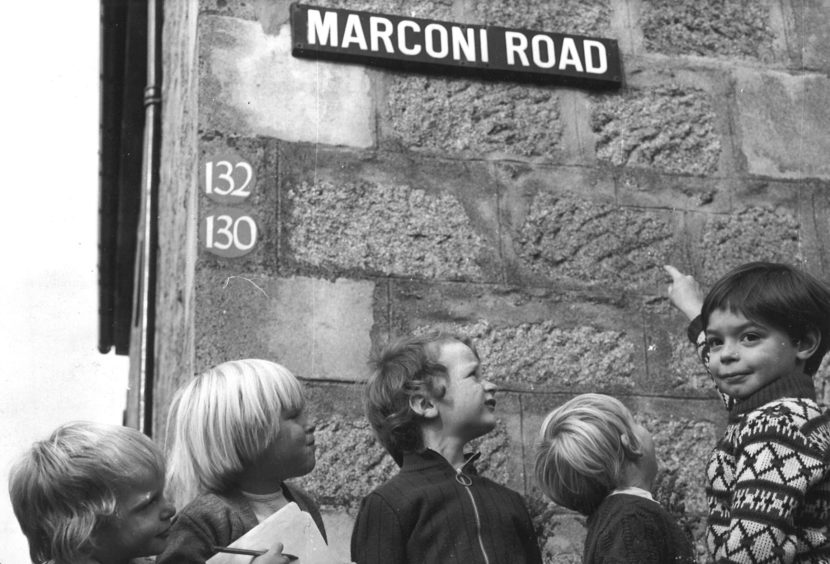

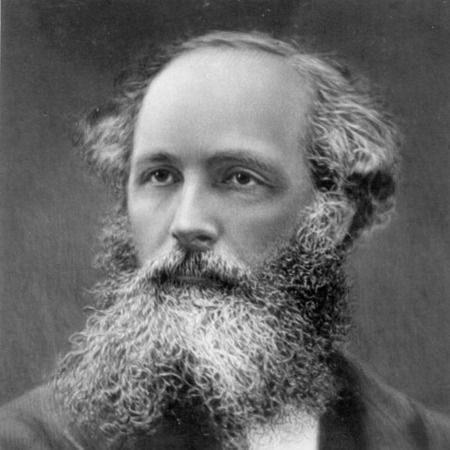

This follows the innovation and imagination of so many pioneering figures, including his compatriot James Clerk Maxwell, Heinrich Hertz and Guglielmo Marconi, whose name has become inextricably linked with the device.

In so many different ways, Mr Bathgate, who has written a new book, Radio Broadcasting: A History of the Airwaves, has devoted decades to boosting its profile in many guises.

He was a founding member of Grampian Hospital Radio at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary – a service which does invaluable work and particularly in the current Covid-induced social isolation.

He also presented shows for North East Community Radio at Kintore and presents music programmes as far afield as Peterhead, The Netherlands and the fabled Radio Caroline.

He has created a series of witty little films, imparting his love for the Doric language, including pastiches of Star Trek and Dallas.

But it’s his passion for radio which shines through the pages of his new production.

He said: “My fascination with it began at a very early age. I was hypnotised by the big, glowing box which sat in the corner of the lounge.

“I would twiddle the knobs feverishly to hear the strange cacophony of whooshing, cracking, whistling and popping noises which came from the wireless.

“Luckily for my parents, I soon got tired of the discordant racket and realised that, if I tuned the dial more slowly, I could hear a lot more, so I would tune around until I heard a voice or a piece of music.

“I have been interested in the medium ever since and I had to be involved in some way, which helps explain why I have done a bit of everything from hospital radio to rock.

“I’m also about to start presenting shows for Radio Caroline Flashback.

“The book came about because I wanted to know more about the people who were behind the development of this fabulous invention which has changed everybody’s lives.”

Mr Bathgate has explained, in meticulous detail, how a group of trailblazers from across the globe gradually pieced together the formula for bringing radio to fruition.

Clerk Maxwell, the Victorian physicist, who was subsequently described as a “genius” by no less a figure than Albert Einstein, was instrumental in the process, while Marconi capitalised on the commercial aspect of producing radio sets for mass consumption.

There is a wonderfully evocative description of the radical, albeit ramshackle methods which were employed by a small ragtag band of men who gathered on a chilly evening in 1922, with a grand ambition, just a couple of years after radio’s potential materialised.

As the author explained: “It was St Valentine’s Day, but any romantic thoughts had been pushed to the back of their minds. These men were preoccupied with something else – something far more important. As the hands of the timepiece on the wall inched towards 8pm, they scurried around tweaking and adjusting their equipment.

“This wasn’t a crack team of military personnel about to embark on a secret mission.

“They were a disparate bunch of engineers brought together by an enterprising Italian called Guglielmo Marconi and, under the auspices of his company, they were about to launch Britain’s first regular radio broadcasting service.

“At the appointed hour, the transmitter and the aerial crackled into life.“

It was like the arrival of the telephone and the television, marking the dawn of a new era.

But it was a wonderfully eccentric occasion, with something of Harry Enfield’s character Mr Cholmondley-Warner about it, as Mr Bathgate explained.

He said: “One of the early pioneers was Captain Peter Pendleton Eckersley who was the reluctant star of the UK’s first station 2MT at Writtle, near Chelmsford.

“He was an engineer and never intended to step in front of the microphone. However, one night, in March 1922, he decided to stay behind and get involved with that evening’s broadcast.

“He had a couple of drinks beforehand for Dutch courage and that relaxed him. He played around, improvised comedy sketches and operatic parodies and played records, often off kilter and at the wrong speed.

“The engineers at Writtle had perfected what Eckersley called the ‘ultimate volume control’. This basically consisted of the engineer moving the microphone closer or further away from the gramophone horn.

“Eckersley eventually became the first chief engineer of the BBC.“

These early days involved giant technological machines and laborious recording processes, but they were accompanied by rapid strides as international scientists and the worlds of commerce and entertainment combined to grasp the potential of radio.

Within the next two decades, there was the establishment of the BBC, the creation of talking pictures, increasingly sophisticated programmes and the arrival of the presenters, who gradually morphed into modern disc jockeys and talk show hosts.

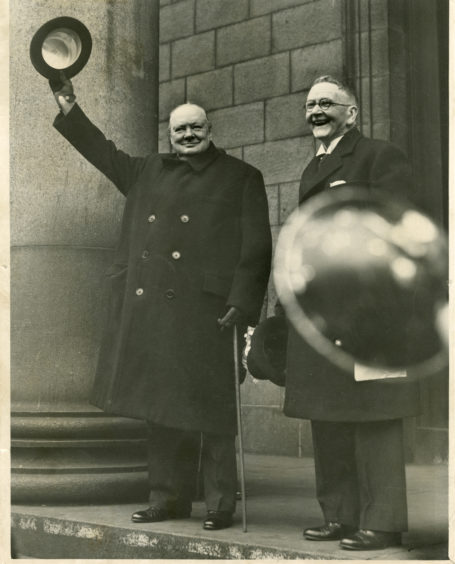

On the political stage, it proved a force for both good and evil, especially as a means of political leaders delivering messages to a global audience.

Yet, as Mr Bathgate has outlined, it was the intimate nature of the medium which offered an enduring appeal to so many listeners – the sense that somebody in the next room was having a conversation with you.

During the last century, the master practitioners of radio, from Alistair Cooke (Letters from America) to Terry Wogan and Roy Plomley (the original host of Desert Island Discs) have always adhered to that philosophy.

Mr Bathgate’s fascination with his specialist subject runs through the pages. And he has thrived on his own idiosyncratic forays into the radio game.

He added: “Most of my memorable experiences have happened at outside broadcasts. One of them happened at Inchmarlo Golf Course at Banchory a few years back.

“I was interviewing a dance teacher about the courses she ran and she invited me to join her onstage to help demonstrate a particular dance.

“She handed me a grass skirt and told me to wear it. I ended up doing a belly dance in front of a large crowd with various members of the Emmerdale cast.

“Another memorable moment also involved a couple of the cast of Emmerdale at the old Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre.

“I have interviewed Chris Chittell, who plays Eric Pollard in the soap, several times and on this occasion he was joined by his wife Lesley Dunlop, who plays Brenda Walker.

“I was placed between them and, while I was interviewing Lesley, I was aware that Chris was up to some mischief but wasn’t really sure what.

“When the interview was over, I got up to thank them and I promptly fell over.

“Chris had tied my shoelaces together.”

There’s a rich sense of that japery and cracker-barrel boffinry in Mr Bathgate himself – which makes his new book such a riveting roller-coaster ride.

- Radio Broadcasting: A History of the Airwaves, by Gordon Bathgate, is published this month by Pen and Sword.

The genius of James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell was one of the most famous figures in the history of science.

And his pioneering achievements laid the groundwork for everything from Einstein’s theory of relativity to the creation of modern electronics.

However, a new book about the Scot has revealed his hitherto secret past as a driving force in the construction of the famous Music Hall in Aberdeen’s Union Street during Maxwell’s time as a professor in the Granite City.

The young Victorian was a key member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science organisation and he was determined to persuade them to stage its annual meeting in the north east.

So he was thrilled when it was agreed that the 1859 convention would be held in Aberdeen. But there was a rather big glitch: the city (which only had a population of 35,000 in those days) had no venue which was suitable for the sort of large-scale lectures and discussions which were arranged at the event.

Nonetheless, this didn’t deter the protagonist of Brian Clegg’s book – Professor Maxwell’s Duplicitous Demon – and he set about making sure that Aberdeen created an auditorium which was worthy of hosting major occasions.

As the author said: “With Maxwell among its shareholders, the Music Hall Company set to work on the rapid construction of a spacious venue in Union Street.

“The imposing 50-foot-high internal space was capable of seating 2,400 people and is still a major feature of the cityscape today.

“The British Association of Science meeting, which was opened by Prince Albert, was a huge success.”

However, there was a curious backdrop to the story, with the Music Hall Company continuing to send dividends from its proceeds to Maxwell at the long-defunct Marischal College through to the early 1900s, long after his death.

Indeed, this led to the lawyers responsible for dealing with the payments eventually placing an advertisement in what is now the Press & Journal, asking for “Mr James Clerk Maxwell to come forward”.

Mr Clegg added: “They were entirely unaware of either his fame or his demise [from cancer] in 1879 at the age of just 48.”