Scottish spiritualist medium Helen Duncan, aka Hellish Nell, was the last person to be imprisoned under the Witchcraft Act of 1735. Her supporters continue to campaign to have the Callander-born fraudster – who was rumbled for mocking up fake ectoplasm and “spirits” – posthumously pardoned of the 1944 conviction.

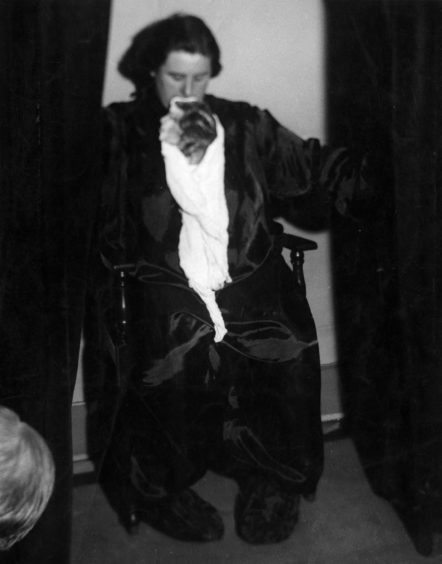

Dressed in black, Helen Duncan sat at the front of the room, lit only by a dim red light, as she conducted a séance.

A deathly silence gripped the audience as the plump woman’s eyes rolled back in her head, her body went limp and she entered a trance.

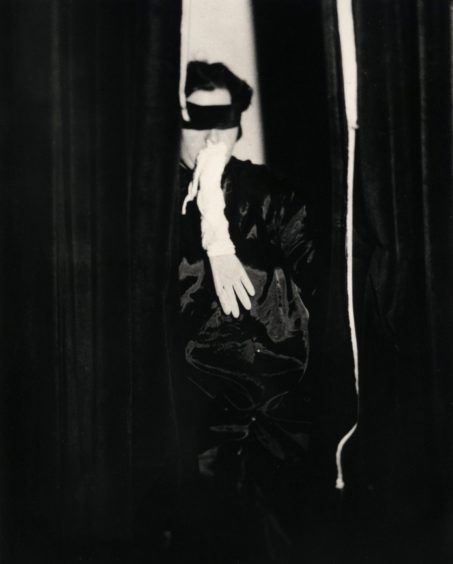

Silence turned to gasps of incredulity when, from behind a curtain, a ghostly white figure appeared and began to speak.

Pulses raced when Duncan, slumped in her chair, started to produce “ectoplasm” from her mouth and nose which took on a human shape.

Duncan, who became known as Hellish Nell, is known as being Britain’s last witch but she was nothing of the sort.

She was a spiritualist medium, hailed by many as one of the greatest that ever lived, and by others as a shameless fraudster.

In 1944, Duncan was the last woman to be tried and found guilty of witchcraft in the UK. She was jailed for nine months for having breached the Witchcraft Act of 1735.

Even prime minister Winston Churchill, who was one of the medium’s clients, deemed the conviction “obsolete tomfoolery” and demanded to know “why the Witchcraft Act, of 1735, was used in a modern Court of Justice?”

By some accounts, Churchill also visited her in jail.

Hellish Nell

Helen Duncan was born Victoria Helen MacFarlane in Callander, Perthshire, on November 25 1897.

She was said to have displayed psychic abilities from a young age, having visions, seemingly communicating with spirits and getting visits from ghosts.

She would also predict doom and destruction for all sorts of people.

Her parents were wary of her unusual “gift” and warned her against using it.

When Duncan reported to have seen a dead soldier, her mother scolded her and warned: “They’ll put you in jail as a witch”.

Known for acting like a tomboy, her rowdiness, bad-temper and outbursts of hysteria gave rise to her being nicknamed Hellish Nell.

After leaving school, she worked at Dundee Royal Infirmary, and in 1916 she married Henry Duncan, a cabinet maker and wounded war veteran, who was supportive of her supposed paranormal talents.

They’ll put you in jail as a witch.”

Duncan worked part-time in a bleach factory and the couple went on to have six children.

By the 1930s, Duncan had become one of Britain’s most celebrated mediums, travelling across the country to conduct séances.

These were always oversubscribed – there were hundreds of applications to take part – and they were surrounded in furious debate.

Ectoplasm

Duncan claimed to be able to permit the spirits of recently deceased people to materialise.

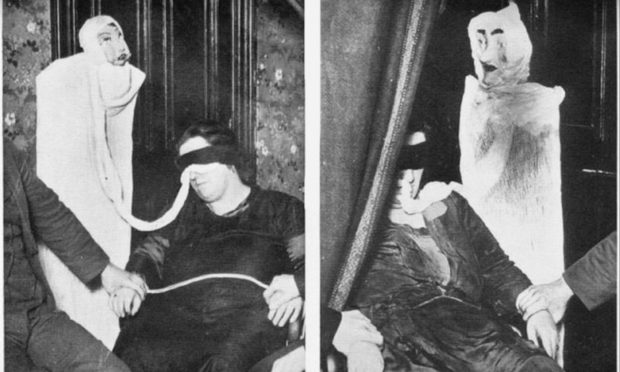

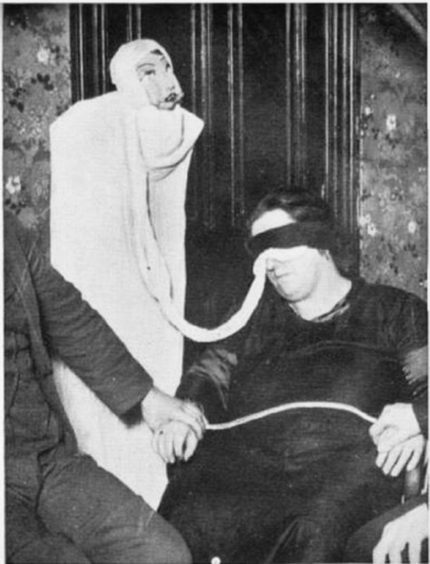

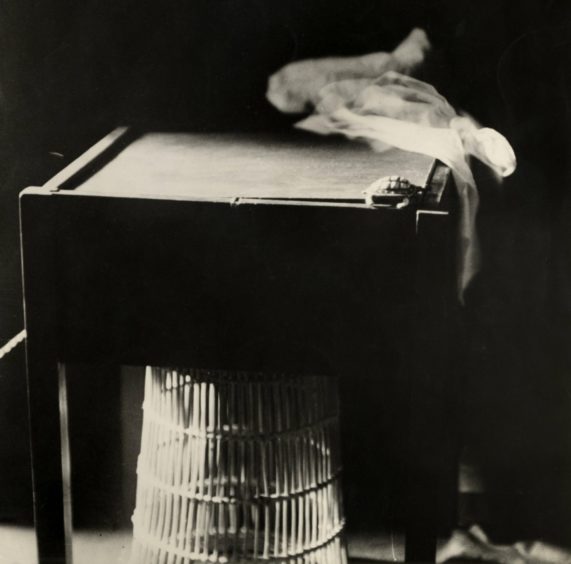

Her séances frequently included strings of otherworldly white ectoplasm produced from various orifices, as well as ghostly images of the faces and bodies of departed “spirit guides.”

Such activity attracted a great deal of scepticism and in 1928, photographer Harvey Metcalfe took various flash photographs of Duncan and her alleged “materialisation” spirits during a séance.

The photographs revealed the spirits to be fraudulently produced, such as a doll made from a painted papier-mâché mask draped in an old sheet.

A 1931 investigation by famed psychic researcher Harry Price concluded that the ectoplasm was actually cheesecloth covered in egg whites, iron salts, and other chemicals, which Duncan stored in her stomach and then regurgitated.

The “spirits” were pictures of heads cut from magazines, while a “spiritual hand” glimpsed in one séance was revealed to be a rubber glove.

Later in 1931, Duncan was paid £50 by Price to perform a number of test séances.

She reacted violently at attempts to X-ray her or allow infra-red photography which was then in its infancy.

Fraudulent

Price described Duncan as a “fat female crook”.

He said: “She refused to be X-rayed. Her husband went up to her and told her it was painless. She jumped up and gave him a smashing blow on the face which sent him reeling.

“Then she went for Dr William Brown who was present. He dodged the blow.

“Mrs Duncan dashed out into the street, had an attack of hysteria and began to tear her séance garment to pieces. A 17-stone woman, clad in black sateen tights, locked to the railings, screaming at the top of her voice.

“A crowd collected and the police arrived. The medical men with us explained the position and prevented them from fetching the ambulance.

“Could anything be more infantile than a group of grown-up men wasting time, money, and energy on the antics of a fat female crook?”

Psychologist William McDougall, who attended two of the séances, pronounced her “whole performance fraudulent”.

Following the report written by Price, Duncan’s former maid Mary McGinlay confessed to having aided Duncan in her mediumship tricks, and Duncan’s husband was suspected of acting as her accomplice by hiding her fake ectoplasm.

Mrs Duncan dashed out into the street, had an attack of hysteria and began to tear her séance garment to pieces. A 17-stone woman, clad in black sateen tights, locked to the railings, screaming at the top of her voice.”

However, the investigations failed to dim enthusiasm for Duncan’s séances.

Neither did being rumbled as a fraud during a séance in Edinburgh in January 1933 when the “spirit” of a little girl called Peggy materialised.

The lights were turned on and the “spirit” was revealed to be made from a cloth vest.

This was used as evidence that led to Duncan’s conviction on the Scottish offence of fraud at Edinburgh Sheriff Court in May 1933.

Otherworldly disclosures

It wasn’t until the Second World War that her séances began to attract the concern of the establishment.

In 1941, she is said to have informed her sitters of the sinking of a warship before the government had publicly released the information.

In 1943, a sailor wearing a hat with HMS Barham emblazoned on it supposedly appeared at one of her séances.

The Barham was not declared officially lost until a few months later.

The War Office became increasingly anxious about Duncan’s otherworldly disclosures – might she even be a spy? – and were concerned she might somehow uncover top-secret plans.

Two lieutenants were among her audience at a séance on January 14 1944.

One of these, Lieutenant Worth, was not impressed as a white cloth figure appeared behind the curtains claiming to be his aunt – he had no deceased aunt.

In the same sitting another figure appeared claiming to be his sister but Worth replied his sister was alive and well. Worth was disgusted and reported it to the police.

Undercover policemen interrupted one of her sittings on January 19 1944 during which a white-shrouded figure appeared which turned out to be Duncan herself.

She was arrested and charged with vagrancy, conspiracy, larceny and contravening the Witchcraft Act of 1735.

The case, which included 75 defence witnesses, was a media sensation, with newspapers taking the opportunity to print cartoons of broomstick-riding witches.

She was not, however, on trial accused of being a witch.

She was accused and found guilty of “pretending to exercise or use human conjuration” and was sentenced to nine months in Holloway Prison in London.

Duncan became the last person in Britain to be jailed under the act.

Death

On her release in 1945, Duncan promised to stop conducting séances.

In 1951, Churchill finally repealed the 200-year-old Witchcraft Act, but Duncan’s conviction stood.

She died five years later, in 1956, at her home in Edinburgh, shortly after yet another police raid.

Officers burst in and arrested her while she was in a trance during a séance.

Spiritualists said the experience left her gravely ill, with second-degree burns across her stomach.

However, her medical records showed she had a long history of ill-health and as early as 1944 she was described as an “obese woman who could only move slowly as she suffered from heart trouble”.

Pardoned

Descendants and supporters of Duncan continue to campaign to have her posthumously pardoned of witchcraft charges.

The official Helen Duncan website describes her as “the world’s greatest materialisation medium who suffered at the hands of ignorance”.

Her Edinburgh-based granddaughter, Mary Martin, is determined to remove the stigma attached to her late grandmother’s name.

In an interview in 2008, she said she believed the 1944 conviction was “silly, ridiculous really”.

“What were they doing, in the middle of war, trying an old lady for witchcraft?” she said.

Last year, Callander Community Council suggested naming a street in a new development in the Perthshire town, “Duncan Drive”, in her honour.

The spiritual medium’s family got on board with the proposal.

What were they doing, in the middle of war, trying an old lady for witchcraft?”

Granddaughter Margaret Mahn, who was born in Dunfermline but lives in Tennessee, said: “I would be honoured to have a street named after my grandma. Many people have asked me if there are any memorials set up in Callander and I’ve had to say ‘no’.

“Many individuals visit Callander every year just because that is where Helen Duncan is born.

“My dream is to have a memorial in Callander dedicated to my grandmother so that people can visit there.”