Maureen Kelly can recall the exact moment when she recognised the importance of joining forces with her colleagues in Braemar to create an account of how their community had been affected by conflict.

It stemmed from the sadness she felt while attending the Armistice commemoration last winter at the north east village’s war memorial, situated across from the Fife Arms Hotel.

She explained: “As the names of the dead were being read out, I realised that most of those standing around no longer knew anything about who the men were or when and where they died.”

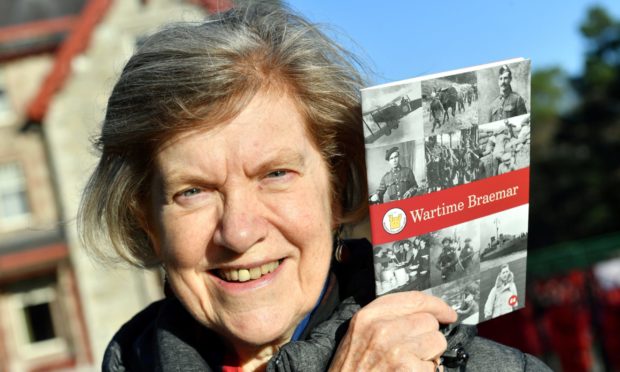

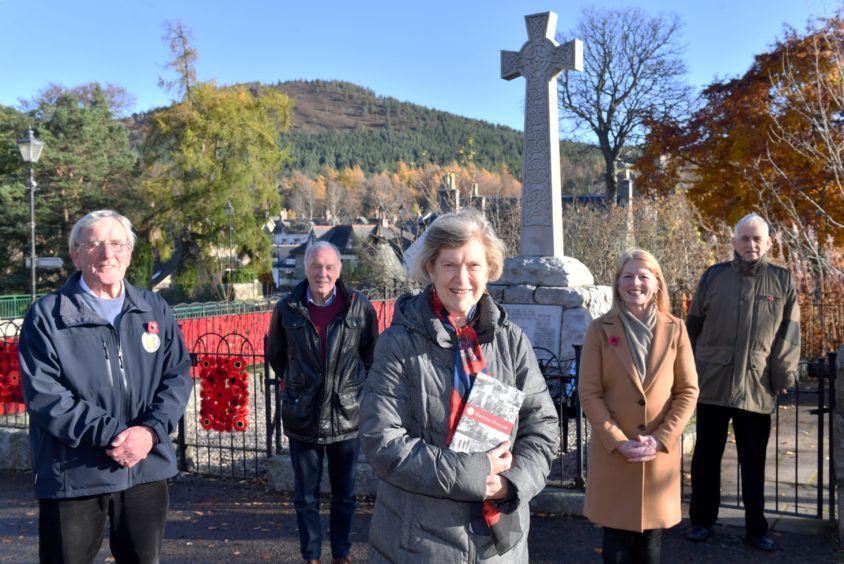

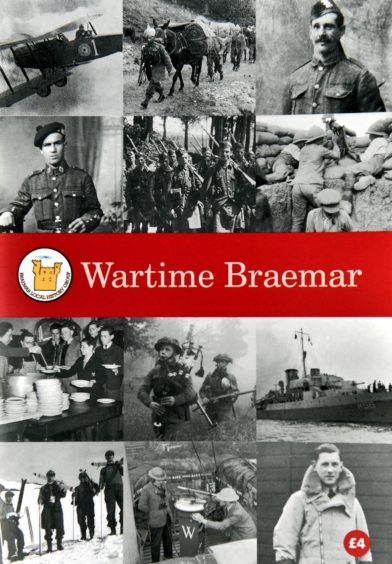

A year later, Mrs Kelly and her friend Fiona Hunter and husband Tom, along with representatives of the Braemar Local History Group, Doug Anderson and Brian Wood, have produced a fascinating work which chronicles the extent of the sacrifice which was made by residents during the First and Second World Wars.

Belgian refugees

Yet they have moved beyond their original remit and highlighted a string of remarkable stories involving such diverse themes as a rogue Zeppelin, Commandos training in the Cairngorms with famed mountaineer Sir John Hunt, Belgian refugees being looked after by locals and the Canadian lumber camp which was established on the Mar Estate.

The authors met with the Press and Journal in the build-up to Remembrance Day at the war memorial, which lists the fallen soldiers from both major conflicts in the 20th century.

Mrs Kelly also produced a poignant photograph of a group of young Gordon Highlanders marching off together as they headed for Europe.

Some are smiling, others look pensive, but they look proud of having joined the campaign, even though many of these north east troops would never return to their homeland.

As Mrs Kelly remarked: “It’s a picture with a lot of power and I find it heart-rending.”

Zeppelin led astray in Deeside

While these soldiers were in the trenches, some semblance of normality remained in the environs of Braemar.

But there was an exceptional day on May 2 1916 when a giant Zeppelin drifted over Deeside during an ill-fated mission to attack the Forth Bridge and the British fleet at Rosyth and Invergordon and cause civilian panic through terror bombing.

As the book notes: “Fortunately for Scotland, the weather that night was appalling and Zeppelin L20 got lost.

“Confusing the Rivers Forth and Tay and thinking that the Eastern Grampians were the Fife coalfields, the crew dropped a bomb there, causing little more damage than an injured horse and some broken windows.

“Blinded by the rain and mist, L20’s wayward journey continued up Deeside and Glen Lui. Realising he was completely lost, the Zeppelin commander dropped a water flare, hoping it would show him to be over the sea.

“Great was the surprise and fear of the McDonald family below in their remote Highland cottage, Luibeg, to hear the sound of airship engines.

“’It made an afa queer noise, a Zeppelin – zoom, zoom’, recalled Nell McDonald.”

Since it was running out of fuel, the L20 had no option but to attempt to return home. However, the craft eventually crash-landed in Norway, where the majority of the crew were interned for the rest of the war.

Yet, five years later, Nell’s father, Sandy, found an object buried in the heather and wondered whether it was an explosive device.

Prince of Wales

Edward, the Prince of Wales, with whom Sandy was stalking a few days later, was fascinated by the discovery, took it to the Air Ministry for identification, and was told it was the nose-cone of the Zeppelin.

The Prince returned the rare artefact to the family with a short note: “Sandy McDonald from Edward P. It’s quite safe now!”

The cone remained in their possession for many years, but can now be seen at the Grampian Transport Museum in Alford.

Crack commando troops were trained in Braemar

After a calamitous attempt by the Allies to resist the German invasion of Norway in 1940, the British realised they needed an elite fighting force which would be effective in extreme winter mountain conditions.

And so it was that, in December 1942, they established the Commando Snow and Mountain Warfare Training Camp (CSMWTC), which was based at the Fife Arms Hotel in Braemar.

The first Commanding Officer was Squadron Leader Frank Smythe, an accomplished mountaineer, and his second-in-command and chief instructor was Major John Hunt, who subsequently earned global fame after leading the successful ascent of Mount Everest in 1953.

Alpine conditions

As Wartime Braemar relates: “Commandos attending the courses lived, not in the luxury of the hotel, but in two-man tents in Glen Clunie and they were provided with clothing suited to alpine conditions

“Instead of greatcoats and knitted woollens, they wore loose string vests under angora shirts, long drawers with seamless legs, wind-proof smocks and trousers, peaked caps with ear flaps, cold weather boots, gloves and goggles.

“Frank Smythe told the Alpine Club in 1945 that the camp at the Fife Arms Hotel was ‘well stocked with Greenland sledges, ski and snow shoes’.

“There was even talk of recruiting a dog team from the local canine populace which ranged from Alsatians to Pomeranians: it would have provided a noble spectacle.

“There was one problem, however – very little snow that winter.”

But nonetheless, three full Commando units, 1, 4 and 12 were trained at Braemar from December 1942 until around the end of May 1943 when it was decided they should transfer to Wales for more specific instruction in rock climbing.

These courses were not for the faint-hearted. They lasted six weeks and participants were tested with a series of very strenuous tactical and physical exercises.

The trainees would have to carry a 70lb pack of food and equipment – including weapons and ammunition – on their back, and were often required to scale several high tops and spend days in Arctic conditions, sometimes living in dug-out snow holes and surviving on pemmican – a mixture of dried meat, fat and dried berries.

The initiative generated some of the finest fighters in British military history. One of their number was Bill Kelly, the father of the new book’s committee-author Tom.

Refugees and foreign troops flocked to Braemar

The new work relates how people from different countries and contrasting backgrounds arrived in Deeside during the different conflicts.

Early in the First World War, 250,000 refugees, around 95% of whom were Belgian, fled to the UK and the Daily Telegraph established a “Shilling Fund” to help them.

Princess Dolgorouki – a very wealthy Edwardian socialite, married to a Russian prince, who had rented Braemar Castle since 1897 – became involved in many of the town’s activities and took the lead in arranging for the collection of shillings.

Warm garments

The community responded generously and, by October 1914, had donated 889 and a half shillings and the Braemar YWCA also undertook “noble work, by preparing warm garments for little refugee boys and girls”, as did the Parish Church Guild.

In the Second World War, there was also an influx of Indian military personnel to assist with the mules, who were invaluable in ferrying equipment on long, gruelling marches.

Their arrival sparked plenty of interest among the Braemar residents, but everybody was pulling together in a common purpose. Friendships were formed, bonds established, and some of the Indians stayed in the region after the war.

Lest We Forget

The authors have unearthed an abundance of material during their research and there are quirky, humorous and offbeat tales of Dad’s Army, the creation of new hospitals and the generosity of so many residents in Braemar.

They have also recounted how around 200 Canadian woodsmen, belonging to No 25 company, were sent to the village in March 1942 and set up a lumber camp, while constructing roads, a light railway and a wooden bridge across the River Dee.

These men were popular with people of all ages. They played football games with the Belgian refugees and local children, gave them presents at Christmas, played in the local pipe band and, as it is noted discreetly: “Their presence at dances and entertainments in the village was also extremely popular…especially with the ladies.”

But while there is light and shade in Wartime Braemar, they haven’t glossed over the scale of the sacrifices made by so many different people throughout the long periods of conflict.

Dreadful crash

This includes the dreadful crash of a Vickers Wellington bomber in January 1942 during what was one of the worst-ever winters with regular heavy snowfalls and freezing temperatures.

The craft, with eight men on board, had departed RAF Lossiemouth on what was initially regarded as a routine training flight. After its disappearance, it was listed as missing, most likely over the North Sea, but the plane had actually struck a Cairngorm hillside and was lying undiscovered in deep snow flurries.

It was only several weeks later that the wreckage was spotted by a gamekeeper from the Invercauld Estate and a young lad from Braemar.

The grim remains were in a narrow corrie in Upper Glen Clunie, quite close to the main A93 road.

A search party cleared a path through the snow and, over the next two months – despite often appalling weather – the bodies of the crew were recovered and buried in Dyce Old Churchyard.

Some young people in Braemar fashioned a few rings from a section of the plane’s metal windscreen. And, as the authors said: “At least one of those youngsters remembers wearing her ring for many years in memory of the aircrew who had died.”

Remembrance is at the heart of this community initiative.

And Maureen Kelly and her colleagues worked unstintingly to do the subject justice.

She said: “Managing to identify all the names on the war memorial, including those who couldn’t be traced in 2018, was very satisfying. Researching their war experiences was very moving and we felt it was important to include some details of all their lives.

“There were many surprises in the fascinating and sometimes entertaining stories we received from family records and personal memories of those in the village or who are now living in other parts of the world.

“Other leads and background came from military archives here and even in Canada and also from the British Newspaper Archive, including the Press and Journal.”

Their labours have reaped a rich dividend.

Copies of Wartime Braemar are available from the Braemar Local History Group on maureen@tandemkelly.co.uk