They are the men from RAF Montrose who died in the service of their country and lie buried far from home.

Graham MacIntosh and Lynn Johnson from Montrose Air Station Heritage Centre have been working on a new project in Sleepyhillock Cemetery to discover and clean gravestones that bear the names of these men.

The condition of many of the old memorials in Sleepyhillock make it difficult to read the inscriptions but so far they have discovered over 90 such gravestones.

Ghost of Montrose

The project started after Graham and Lynn worked to restore the grave of a young pilot whose ghost is said to haunt the former air base.

Lieutenant Desmond Arthur from the Royal Flying Corps perished on the morning of May 27 1913 at the age of 29 after a routine training flight from Upper Dysart to Lunan Bay went tragically wrong.

Dr Dan Paton, historian of Montrose Air Station and Heritage Museum, said Lt Arthur’s lonely grave stands far away from the rows of Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones that mark the graves of other men who were killed in flying training at RFC/RAF Montrose.

In fact, it is the first of these many casualties but because the accident happened before the First World War and before the CWGC was formed it is not within the remit of the CWGC staff who look after the 150 military graves in Montrose.

Working in the old cemetery, Graham and Lynn came to know the area around Lt Arthur’s grave and discovered that some gravestones, in addition to the names of family members who were buried there, also bore the names of brothers and sons who had been killed in Belgium and France during the First World War.

These men are not buried there but their families put their names on the family memorial stone so they can be remembered in Montrose.

Several have, fixed to the stone, the bronze memorial plaque presented to the families of all those killed in the war, commonly known as “Dead Men’s Pennies”.

One of them was Captain Angus Mearns, 22, from Montrose who had transferred to the Royal Flying Corps.

Red Baron

He was flying as observer to Captain Norman George McNaughton, 27, from London, in a DH4 two-seat light bomber A7473 of 57 Squadron, on an operation between Keibergmolen in Beselare, Belgium, and Lichtensteinlager, on 24 June 1917, when they were attacked by Manfred von Richthofen, in his all red Albatross DV.

No name struck more fear into the hearts of Allied airmen than the Red Baron.

At the outbreak of war, Mearns was a student of medicine at St Andrews University.

He had joined the university Officer Training Corps in 1913 and as soon as his examinations allowed he volunteered for active service.

He was commissioned into the 11th Battalion of The Black Watch and then posted to the 9th (Service) Battalion in March 1916, where he remained until he was transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in March 1917.

Dr Paton said Captain Mearns and his pilot became the Red Baron’s 55th victim.

His sister Miss Blanche Mearns, English teacher at Montrose Academy, made great efforts to commemorate her brother.

The gold dome, which is such a prominent feature of the 1815 school building, was gilded at her expense in memory of his sacrifice.

Not alone

“The project to restore Lt Arthur’s grave suddenly became much bigger and Graham and Lynn are going to be working in Sleepyhillock for some time,” said Dr Paton.

“Desmond Arthur lies in splendid isolation but he is not alone in Sleepyhillock.

“There are 150 war graves in Montrose cemeteries and not far away are the graves of aviators like himself, casualties of flying accidents at Montrose from both world wars.

“At this time of year we are sure to see images of the vast cemeteries in France where, laid out with military precision, lie the dead of two world wars, each grave marked by an identical headstone, in plots where privates lie next to generals.

“This was the policy adopted by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, formed 21st May 1917, and given the huge task of organising the burial of British and Commonwealth dead.

“Today their work is universally admired for its order and dignity but at the time it was difficult and controversial.

“After the First World War, over half a million corpses had to be dug up and reinterred in the new cemeteries, often against the wishes of families who wanted the bodies of their loved ones brought home for burial or to have their choice of headstone.

“Christians wanted crosses on the graves.

“Traditionalists were unhappy about officers lying next to other ranks.”

Grave markers

Dr Paton said the work of the Commission is there to be seen in many Angus cemeteries where the plots with the familiar simple Portland stone grave markers are well maintained by teams from the CWGC.

He said: “Many of the dead buried here were aviators like Desmond Arthur but not all local casualties are buried here.

“Unlike the families of men who died overseas, the families of men killed in Britain had a choice.

“Their loved one could be buried with full military honours in a cemetery close to where he died or they could opt for the body, under escort, to be brought home for burial in the family plot with the headstone of their choice.

“Not surprisingly, many families chose this option so men and coffins, escorted by men in their best blue, were a frequent sight at Montrose railway station.

“Many men, killed in Angus, are to be found in cemeteries throughout Britain.

“That is also why such a large proportion of the men buried in Angus are from Commonwealth countries or Polish or even German.

“The German airmen buried at Montrose and Arbroath in 1940 and 1941 were given the same ceremony as our own, with flags over the coffin and shots over the grave.

“In 1959 they were re-interred in the Luftwaffe cemetery on Cannock Chase along with 5,000 Germen airmen.

“The CWGC is nor responsible for maintaining the grave of Lt Arthur even though he was a pilot with No 2 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps, nor is it concerned with family graves that carry the names of war dead like Captain Angus Mearns.

“That is why Graham and Lynn are carrying out valuable work in helping to preserve the memory of men from Montrose who died in the service of their country and lie buried far from home.

“Our cemeteries have interesting stories to tell and they are important in the history of our communities.

“Perhaps, now that so many places of recreation are closed to us, the old Victorian custom of visiting cemeteries on Sunday afternoons will experience a revival and if you go to Sleepyhillock, you may well see Graham and Lynn at work.”

Dr Dan Paton discovers more about the life and times of Lieutenant Desmond Arthur

Who was Desmond Arthur?

The inscription on his gravestone tells us nothing other than that he was killed at Montrose.

He was an Irishman who came from a well-to-do family and who joined the British Army in 1908.

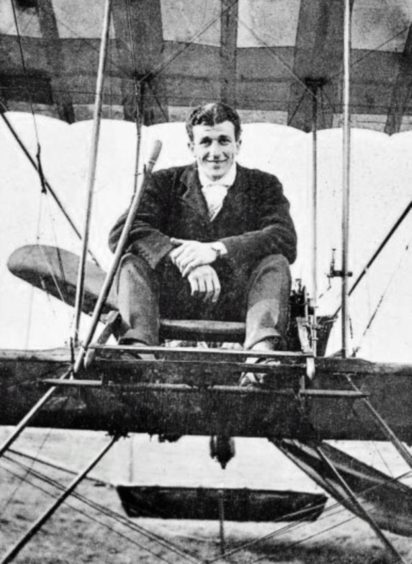

He became fascinated by the new technology of manned flight and became one of the first men in Britain to learn to fly and get his pilot’s licence.

In 1912 the British armed services belatedly recognised that manned aircraft might have military applications and the Army formed the first squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps.

Experienced pilot

The first squadron to be equipped with aircraft were sent to Montrose in February 1913 and Arthur, already an experienced aviator by the standards of the time, joined No 2 Squadron in April.

The Commanding officer, Major Charles Burke, must have been pleased to welcome such an experienced pilot, especially since he was another Irishman.

Desmond Arthur is, perhaps, best known as the Montrose Ghost.

The enquiry into the accident, as so often, blamed the pilot.

His unquiet spirit, protesting against the verdict of the enquiry and how it reflected badly on his skills as aviator, is said to have haunted the officers mess until a new enquiry in 1916 found that the crash was caused by a faulty repair to the wing of his BE2 aircraft.

The ghost, his honour vindicated, was seen to throw some papers on the fire and departed to rest in peace.

He was missed, not least by Winsome Ropner, a young woman whose correspondence with friends showed that she was in love with Desmond Arthur and that they intended to marry.

When his aircraft broke up over Lunan he fell 2,000 feet to his death.

On his broken body was a broach with her portrait, cracked by the impact.