He was the Black Watch hero who died just moments after saving a comrade’s life on the battlefield.

Lance Corporal John Morrison was killed in 1915 at the age of 29 during hours of bitter fighting in France.

He was gallant to the end following the fierce German attack.

Morrison was struck by a bullet in the leg but managed to crawl to the assistance of his officer, who was also wounded.

He helped him to remove his back pack when he was fatally shot.

Morrison’s remains were missing for 100 years until a farmer made the chance discovery of a bone while ploughing his field.

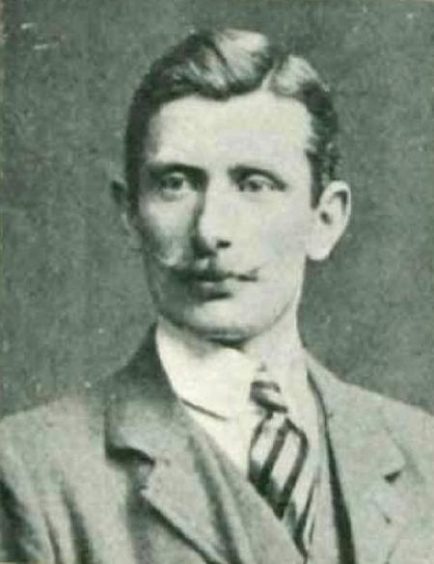

John Morrison

Morrison was born 135 years ago on November 14 1885 at Tomintoul, Moray.

He grew up at the Brodie Castle Estate, Forres, where his father John worked as gamekeeper.

He followed in his father’s footsteps and also became a gamekeeper on the Ardtornish Estate at Morvern, Argyllshire.

Morrison travelled to Perth to enlist with The Black Watch on September 7 1914 just one month after Britain declared war on Germany.

By December he had finished training and was sent as part of a draft of 150 recruits to strengthen the 1st Battalion in France as a fighting unit after the huge losses suffered during the First Battle of Ypres that had subsided only 10 days or so before.

In early 1915 the battalion took up positions around Cuinchy, the southernmost part of the British lines, marked by army intelligence as under threat from a German attack.

About 7am on January 25 a German deserter came in and reported an attack imminent.

When the attack came it was ferocious.

Four enemy mines were detonated in the notorious Brickstacks sector of the front and the line held by the Coldstream and Scots Guards was overwhelmed by a concerted attack.

Amongst the confusion of the battle and the British line at risk of breaking, Morrison found himself fighting bitterly against a determined enemy.

It was during this fighting that the newly appointed Lance Corporal Morrison fell, one of 59 from the 1st Battalion to die on January 25 1915.

Letter

Following his death, his brother received a letter from Second Lieutenant Lewis Willett, which elaborated on the circumstances of his death.

“Some gallant fellow crawled up to me shortly after I was hit, and attempted to assist me off with my pack, but owing to the nature of my wound, I was unable to turn my neck sufficiently around to see who it was,” he said.

“I heard he was hit, and asked him if it was so.

“He replied: ‘Yes Sir’; and when I inquired later, I received no reply, but could just touch his hand by reaching back, and found he was dead.

“From the sound of his voice I thought it was your brother, who was in my platoon, and I hoped it wasn’t so, and that I had made a mistake, for he was one of my most valued men.

“His end was a gallant one, and his was a peaceful conclusion to a career, which, had he been spared to prolong it, he could have looked back on with the justifiable pride of one who has done his work well.”

He was commemorated on the Le Touret Memorial along with the names of 53 of his other comrades who were also killed in action on the same day but had no known graves.

Morrison’s body was found almost 100 years after his death in December 2014.

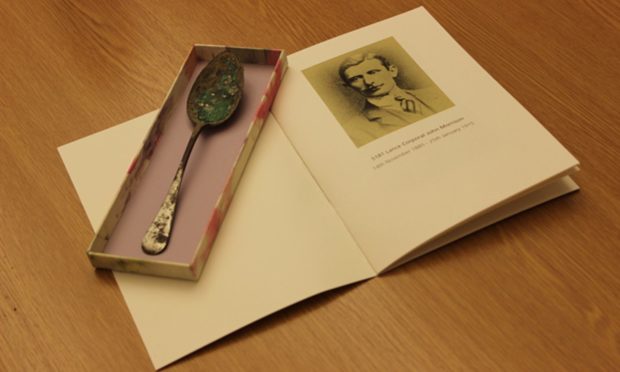

The remains were discovered when farmer Claude Lemaire in Cuinchy, near Arras, found a spoon engraved with his service number 5181.

“While ploughing our field, behind the centre of Violaines, we saw a bone,” he said.

“Out of curiosity, we scratched and found ammunition.

“And then the famous spoon bearing the registration number 5181.

“We called the Commonwealth.”

Investigation

The Ministry of Defence’s Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC), who deal with British Army Casualties, took over the investigation in order to identify the remains.

The archive was able to prove that a Black Watch soldier with the army number 5181 had died in Cuinchy at the time the artefacts suggested.

The JCCC contacted Morrison’s nephew, Ian Morrison, who provided a DNA sample.

Having proven Morrison’s identity, his name was removed from the list of the missing.

He was laid to rest in July 2016 with full military honours, at Woburn Abbey Cemetery, Cuinchy, near the battlefield where he bravely fell.

A new headstone bearing his name was provided by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) who now care for his final resting place.

The death was not the only tragedy to touch the family.

His brother, George, the youngest of the family, died of wounds in April 1918 whilst serving as a Captain with the 1/6th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders.

George’s own son, John, born a little more than seven weeks before his father’s death was also killed in action as a Navigator Flight Lieutenant over Normandy just a month after D Day in World War Two.

Kipling described the Great War battle where Morrison lost his life

The German attack of January 25 was described by Rudyard Kipling in The Irish Guards in the Great War, Volume 1.

He wrote: “Owing to the mud, the (Cuinchy) salient was lightly manned by half a battalion of the Scots Guards and half a battalion of the Coldstream.

“Their trenches were wiped out by the artillery attack and their line fell back, perhaps half a mile, to a partially prepared position among the brick-fields and railway lines between the Aire–La Bassée Canal and the La Bassée–Béthune road.

“Here fighting continued with reinforcements and counter-attacks knee deep in mud till the enemy were checked and a none too stable defence made good between a mess of German communication trenches and a keep or redoubt held by the British among the huge brick-stacks by the railway.”

It was all too easy to be reported unknown or missing in the First World War

The Black Watch raised 25 battalions during the course of World War One and mainly fought in France and Flanders.

By the time of the Armistice in November 1918, 8,000 members of the regiment had lost their lives.

No one could have predicted the scale of casualties.

Battle after battle resulted in hundreds of thousands of soldiers being buried on the battlefields in individual or communal graves.

Due to the highly destructive capabilities of the weapons used and the conditions of the battlefields – the sheer number of casualties meant all too often men were left unaccounted for.

It was all too easy to be reported unknown or missing.

Even if a body was found, identified and buried during the war it did not guarantee that this would remain a final resting place.

Continuous attacks, armies being pushed backwards or pressing forwards meant that many cemeteries, especially on the Front Line, were destroyed. This meant that soldiers whose bodies were once identified were lost again in the chaos.

There are many ways we commemorate the missing and unknown.

Memorial walls, cemeteries and monuments listing the names of those lost among the battlefields and recognise the sheer number of unknown soldiers.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission continues to find and identify the missing dead.