It was the biggest disaster in the history of the global oil industry. And, even today, 35 years later, people with no other knowledge of the history of the North Sea are familiar with the words Piper Alpha.

After the installation was engulfed by flames on July 6 1988, 167 men were killed in the ensuing devastation on a night when everything that could go wrong did go wrong.

Hospitals in Aberdeen were placed on standby for a mass evacuation of casualties. But, as the hours passed, it became horribly clear that precious few were coming back.

Bravery amid the horror

Yet, in the midst of the spiralling horror and appalling casualty list, there were so many remarkable acts of bravery that 20 men were subsequently decorated for their part in the rescue efforts — some of whom sacrificed their own lives to save others.

Charles Haffey, a Fife man with the smack of brine in his veins, was among those who was honoured with a George Medal from the Queen in December 1990.

But the award meant less to him than the recognition he had been able to help some poor souls escape from a scene which was straight out of Dante’s Inferno.

The Scot was among the UK military personnel who travelled to the South Atlantic in the early 1980s as part of the British fleet which fought in the Falklands conflict.

After that experience, he recalled sitting in a bar with his confreres in Methil and chewing the fat over what they would all do in the future.

Mr Haffey told the gathering he had decided to join the Merchant Navy and relocate to Aberdeen to start a new career, working in the expanding oil and gas industry.

One or two in the crowd expressed reservations.

Nobody imagined anything like this

But, as he told his friends: “What’s the worst that can happen?”

Sadly on that grim July night and morning, as one of the crew members on the stand-by vessel Silver Pit, he discovered the answer when he was part of the rescue team which responded to an unprecedented catastrophe.

He and his colleagues on board the converted fishing trawler were the first to arrive at the scene and none of them could grasp the scale of what was unfolding.

And yet, even as they strove to pull casualties from the water and deal with a situation which was beyond anybody’s comprehension, Mr Haffey maintained a combination of sangfroid and camaraderie with his colleagues.

Not that there was any real alternative in the circumstances.

He said: “I don’t know whose idea it was to use old trawlers to deal with emergencies in the North Sea. Because the Silver Pit was a really old boat, dating back to the 1940s.

“Let’s just say I wouldn’t be buying them a beer.

The heat was incredible

“But, on that night when the platform blew up, we couldn’t afford to worry about anything else than doing our best to help the poor lads who had been on the rig.

“It was a vision of hell. Quite frankly, you could not have imagined anything like that would ever happen. As we were approaching Piper Alpha, there was this incredible heat and flame and noise around us.

“If you have ever been in the Navy, you will know that seamen tend to have a gallows humour. Bad things sometimes happen and you have to be prepared to deal with them.

“Yet, from the moment we heard the explosion and the alarm, it was pandemonium. I wasn’t aware of time passing – it was just a blur.”

They were heroes in a hopeless situation

He and his fellow crew members James McNeill, Andy Kiloh and James Clark jumped aboard their fast rescue craft and went to the platform several times to pick up survivors. On their final trip, they found men clinging desperately to life rafts and debris, many of them grievously burned.

For those who returned and were offered an opportunity to rebuild their lives, the memories were indelibly etched on their minds. Many suffered from PTSD, their marriages and relationships often fell apart and they found it difficult to move on when so many friends and colleagues had been ripped away from them.

Mr Haffey has refused to let the tragedy define him, but it’s obvious that the sights and sounds from that awful July night have left a permanent mark.

As he stated: “The noise will be the last thing I will hear. I couldn’t believe that flames could be so loud. You are talking ear splitting. We could not hear people who were right next to us and shouting at us. We were reduced to using hand signals.”

“We managed to make a bit of a difference and worked as hard as we possibly could, but the scale of the tragedy was overwhelming. I was only 26, but my military background meant I had already seen casualties in war. Yet this was different altogether.”

George Medal

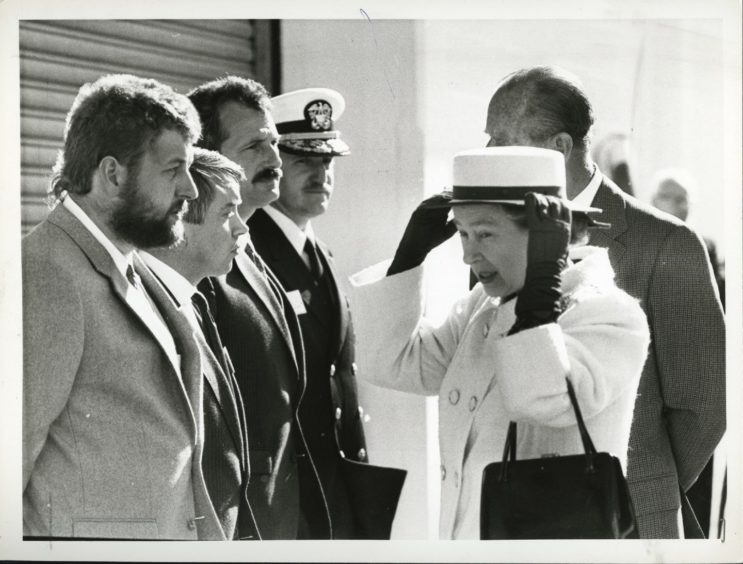

In the winter of 1990, following the publication of the extensive Cullen Report into the disaster, Mr Haffey was one of seven men awarded George Medals for their bravery.

He added: “I was staying with my brother and he told me that this letter had arrived at the house with a royal seal on the back.

“Well, I didn’t know much about what getting a George Medal meant. But when I mentioned it later on to my dad – who was a fireman – he shook my hand and said ‘congratulations’.

“Then the five of us who had survived – sadly, two of the others didn’t make it – travelled to Buckingham Palace in December 1990 and it quickly became a big deal with the press asking for our response and our pictures and the TV people wanting to talk to us while we were down in London.

“But you know, I always thought it was more of an award for all the men who joined the rescue mission that night.

“Nobody was any more or less brave than the others. We all went into Dante’s Inferno. Some of us came back; others didn’t.”

Mr Haffey is a genial character with a desire to help others, who scarcely gives the impression of being one of life’s raging bulls. Yet he admitted it took him around a decade to stop feeling angry about what happened before, during and after the Piper Alpha conflagration.

Anger after the disaster on the North Sea

Eventually, he concluded: “You just have to reason with yourself: no matter how angry you might get about this, the fact is you are not going to bring those guys back.

“If that means talking about it, and reminding youngsters of just how bad it was, it’s very important to get the message across. Nothing was worse than this. Nothing.”

Despite turning his back on a career at sea after Piper Alpha to become a civil servant, Mr Haffey still has a hankering for the Big Blue and loves the coastline around Fife.

Fife coastline

He said: “I was invited on to HMS Kent a few years ago and it was the first time in ages I had been on a ship. Well, I looked around me and I shed a wee tear.

“I still have moments where I remember living in Aberdeen and I head up there and go to the harbour and down to the beach and these places bring back so many memories.

“Piper Alpha didn’t destroy my love for the sea. I loved being in the north-east and the people were fantastic after the tragedy and showed so much compassion and much concern.

“Yet, of course, life was never quite the same for anybody again. It was one of those awful situations which sparked a chain reaction, and there was a terrible price to pay.

“But the banter, the humour and the camaraderie and the feeling of being out in the ocean and on the waves…I still miss it even after all these years.”

Full list of heroes honoured

George Medal

Brian Philip Batchelor (posthumous), Hull

James Herbert Clark, Dundee

Charles Alexander Haffey, Methil

Andrew James Kiloh, Aberdeen

Iain Letham, Gourdon

James Paul McNeill, Oban

Malcolm John Storey (posthumous), Alness

Queen’s Gallantry Medal

John Barr, Turnberry

Donald Brown, Glenrothes

Edward Cross, Aberdeen

Christopher Michael Dunwoody, Great Malvern

William John Flaws, Buckie

Ian Fraser Mackay, Kilwinning

Stanley Roderick Mackenzie Macleod, Southampton

Peter Thomas, Plymouth

Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct

Barry Charles Barber (posthumous), Stranraer

Robert Carroll (posthumous), Culter

William Francis Clayton, Newcastle

Gareth Paul Parry Davies, Colchester

Robert Argo Vernon, Falkirk