A charming account of a walking holiday in the Cairngorms just before the Second World War has been brought to life.

Stephen Leather from Bingley transcribed his aunt Marjorie Leather’s 16,000 word diary of her small party from West Yorkshire’s 10 day walking holiday at Inverdruie just outside Aviemore in the summer of 1937.

“Why did I decide to transcribe Marjorie’s diary?” said Stephen.

“Marjorie did not have any children and when she died most of her property went to her long-time partner, Winnie.

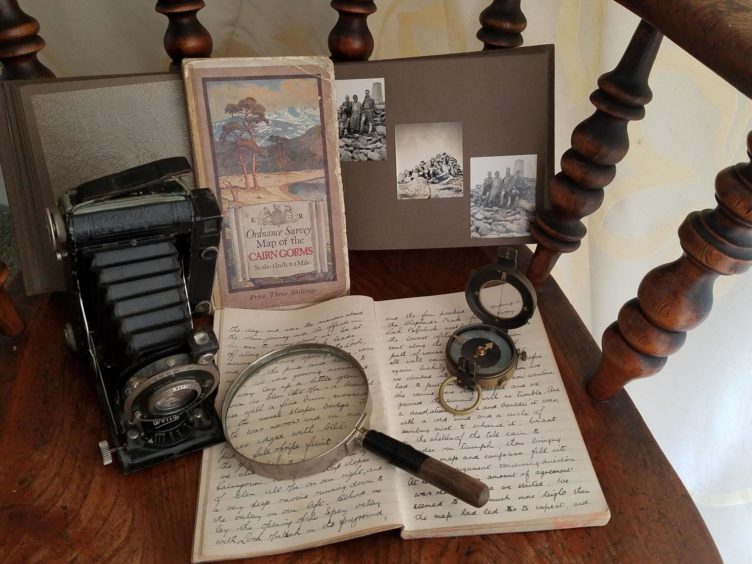

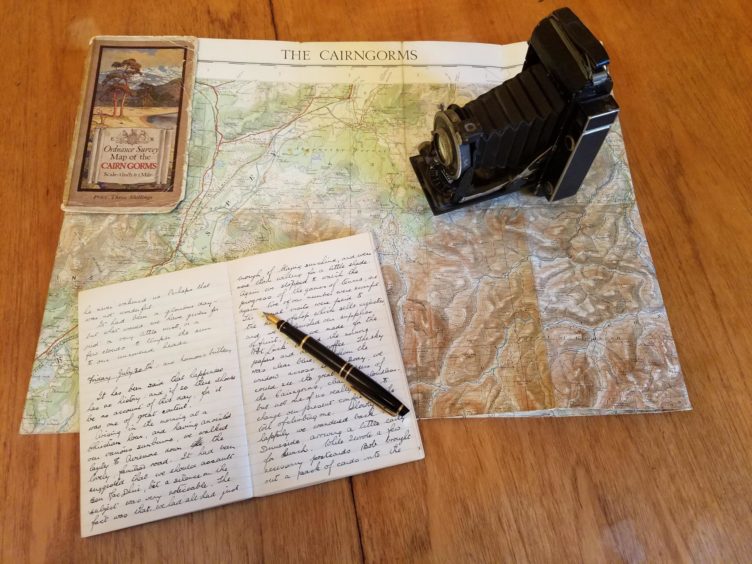

“Somehow I got her account of the holiday, and later my dad’s photos and camera.

“I enjoy writing and the Covid shutdown gave me the opportunity to share these with family members.

“When transcribing her writing I was able to trace their route on a modern Ordnance Survey map.

“My father, who was 21 at the time took some photos.

“I have their original map and my father’s camera.

“I’m so pleased that I have been able to bring this special holiday back to life.”

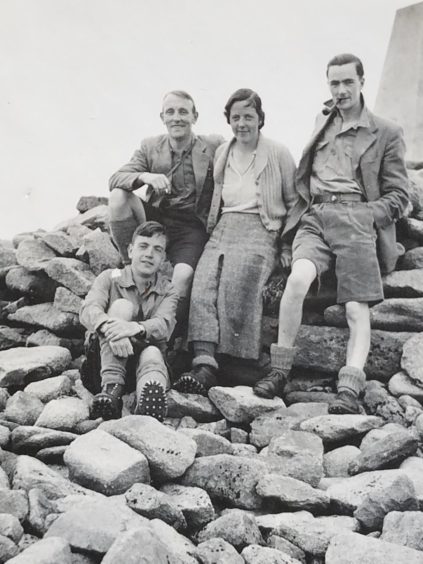

The party which met on the platform of Shipley Station in 1937 were Marjorie, her younger brother, Bernard – always known as Bob – her fellow teacher Norman Cockburn, his wife Muriel and his mother, Mrs Cockburn.

New guests

As their train for Leeds pulled into the station there was the final member of the group, Bob’s friend Harry, who was “grinning and waving from one of the front compartments”.

Harry had to return to Bradford a couple of days before the others, and their landlady, at Druieside, Miss Macintosh, juggled the accommodation to make room for two new guests, Ronald (Ronnie) Clark and his aunt.

Although previously unknown to Marjorie, Bob and Norman, Ronnie joined them on the climb of Ben Macdui on the last Sunday of the holiday.

He was about to embark on training to be a teacher at Moray House, Edinburgh, and seemed to fit in with the group very comfortably.

Marjorie’s final diary entry following the 10 day walking holiday expressed sadness that they were now going home and she described how they were all silent “with our rememberings” at the station platform “to store up those moments of living so that they would never fade, tho’ we knew that they must”.

She wrote: “Dressed for civilisation – we walked down to the post box and back again to the garden for a last linger on the garden seat preparatory for a last wander down to the burn.

“As we sat there Ronnie and his aunt turned into the garden carrying a large paper bag.

“When opened it was found to contain tubs of Wall’s ices for all – so we fraternised and ate.

“Afterwards we paid a hurried visit to the burn, where the cherry branch still clung around its boulder brilliant with ripened cherries.

“In the distance, still and misty, the Cairngorms spread their giant shoulders to the sun.”

Missed train

They hurried to the station and climbed into the wrong end of the train, to be hauled out again 10 minutes later in time to see the front carriages set out on their way to Boat of Garten without them.

“We left our luggage and went once more, most unexpectedly to the Pot Luck, as we had two hours to wait for the next train,” wrote Marjorie.

“This visit had a certain flatness about it: we had said goodbye – the climax was past, and here we were still dallying.

“It was like returning for one’s umbrella after taking a loving and eternal farewell.

“We returned to the station to find Ronnie and his Aunt already arrived to meet a relative who was to pass in the train before the one which we must catch.

“They cheered our waiting, and refused to leave us until we were safely aboard on the correct train in the correct section.

“Indeed the station master himself came to see us safely off the premises.

“We stood in the corridor looking at the mountains, their treacherous smooth flanks already so far away, the days among them already fading to memories, and their patches of snow even now like the vague markings made by a piece of chalk.

“No more for us would a great star hang above the pine branches, or an owl wail strangely in the forest: no more should we sit beside the sandy pools of a mountain burn, or count the many bells of the fox-glove, or keep an eye eagerly searching for a spray of white heather among the abundant purple, or watch the dull clouds trailing moodily along the slopes, or curse the tireless sun and the clear sky, or wave a frantic bracken against the hosts of flies: no more would we speak with fond adjectives of the beauty of soup, and the necessity of plentiful supplies of same: no more would we sit in the quiet garden, and lazily murmur, ‘fifteen-two, fifteen-four’.

“And alas, no longer should we argue together about routes and names and distances, while a map lay spread before us, and a compass pointed its steady finger!

“No more would the forest tracks lead us back to the hills.

“Look thy last on all thing lovely!”

Charming evocation of life

Stephen said the narration in the diary “would have little more than passing interest to any one outside the family and friends of the cast, but it is a charming evocation of life in the immediate pre-war days”.

He said the party’s train journey to Scotland, their arrival, and the detailed description of the accommodation paint a more general picture of the time.

He said: “My father, Bob was born in Farsley in 1916.

“He had an elder brother and a sister Marjorie.

“Marjorie was 31 at the time of this expedition and she was an English teacher at a secondary modern school in Shipley.

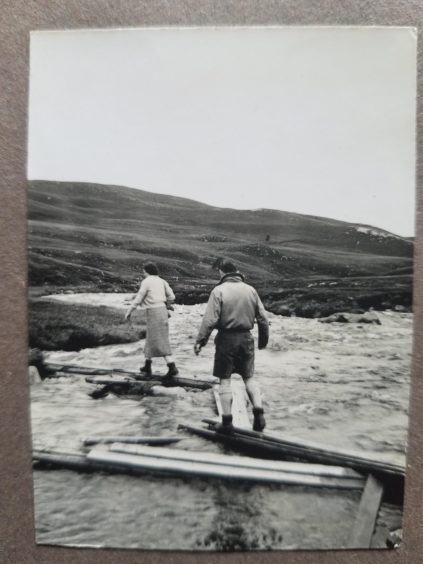

“The family were always keen walkers, having immediate access to the moors such as Ilkley Moor, and further afield by bus or train the Yorkshire Dales.

“Bob’s life-long friend Harry Smith was about Bob’s age and lived in Manningham, Bradford, at the time of this holiday.

“He joined the army at the beginning of the Second World War and was later involved in the liberation of Norway and received a scroll from the King of Norway acknowledging his contribution to Norway’s history.

“On a personal note he was the much loved ‘uncle’ Harry who joined us for many expeditions to the Yorkshire Dales during the 1950s and early 1960s.

“About Norman Cockburn I know very little although he was a teacher and married to Muriel.”

Adulthood lost

Stephen said his father’s tramping was curtailed by his law training, and the Second World War, when he served in the Navy.

He said: “Effectively he, as did so many, lost seven years of young adulthood, followed by years of hard work to re-establish his career and family life.

“But by 1960 we started holidaying in Scotland – Arran, Skye, and the Outer Isles were our destinations for many years.

“How lucky can you get?”