Its rugged scenery, remote locations and resplendent beauty are renowned throughout the world, so it’s hardly surprising many film directors have cried ‘Action’ the length and breadth of Scotland.

Indeed, there is hardly a part of the north and north-east of the country which hasn’t, at some stage, been visited by location directors, as the prelude to a galaxy of stars arriving to appear in segments of some of the most famous movies in history.

Whether we are talking about blockbuster franchises, from the James Bond canon to the Harry Potter series, or Oscar-winning creators of celluloid magic such as Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Bill Forsyth, Sam Mendes and Christopher Nolan, a plethora of classic cinema works have benefited from the Scottish landscape.

The latest Bond movie, No Time to Die, which has been delayed because of the Covid-19 pandemic, includes scenes in the Highlands, including Aviemore, Loch Laggan and Cairngorms National Park, while the BAFTA-winning director of Stan & Ollie, Jon S Baird, will venture to Aberdeen next month to continue work on his latest project.

Yet, almost from the start of the film industry, pioneering figures have journeyed to some of the wildest places in Scotland and been inspired in the process.

And nobody showed greater fortitude or flair than Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

Travelling to the edge of the world on Foula

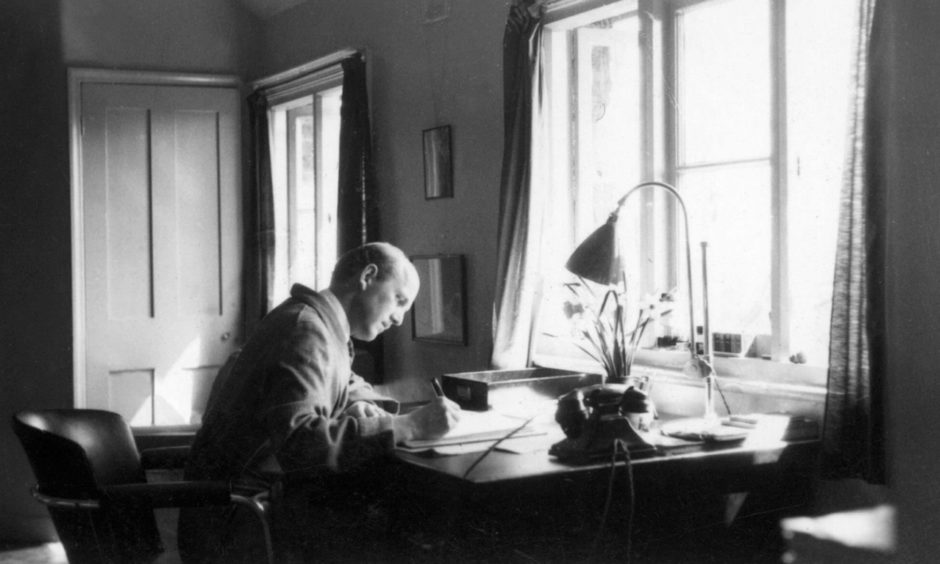

Even today, with dramatic advances in technology available to any wannabe Spielberg, few directors would be comfortable with the challenge of working in one of Scotland’s least forgiving environments, but that didn’t deter Powell as he embarked on an ambitious venture, The Edge of the World, in 1937.

The young director was determined to tell the story of the depopulation of islands such as St Kilda after reading a newspaper article about its evacuation seven years earlier. And although he was not allowed to shoot on the deserted archipelago, he didn’t let that stop him making the film on Foula in the Shetland Islands.

This was no assignment for pampered superstars with inflated egos. As Powell later related, he required a cast and crew who were willing to take part in an expedition to what, before the air service that now exists, was one of Britain’s most isolated locations.

A place where John Laurie wasn’t doomed

They all had to stay for months as the production came together in Spartan conditions: the actors, who included Finlay Currie – a later star of Brigadoon – and John Laurie – who played Private Frazer in Dad’s Army – helped built their own accommodation, had no access to anything but sporadic radio communication, and were at the mercy of the weather even when they weren’t filming in often harsh weather.

Yet Powell, who wrote a book about the venture called 200,000 Feet on Foula, recognised that he and his colleagues had been involved in something special and the film still has a compelling natural beauty more than 80 years later.

He returned to the north of Scotland at the end of the Second World War, this time in the company of Pressburger, and the duo subsequently collaborated on a film which Hollywood legend Martin Scorsese has described as “a masterpiece which made me think anew about the whole art of making films”.

Powell and Pressburger knew where they were going

He was referring to the acclaimed I Know Where I’m Going, which managed to become a magical slice of romance even in the midst of post-war austerity in Britain.

The story, originally titled The Misty Isle, faced myriad challenges and, in some respects, it’s a minor miracle it ever came to fruition. The original stars, James Mason and Deborah Kerr, withdrew, with the latter unable to escape from her contract.

Mason, who didn’t want to go on location – and especially to an island such as Mull in 1945 – was replaced by Roger Livesey, but there was an issue with him as well: he was appearing in a West End play in London, so he couldn’t commit to joining the crew.

However, as the late film critic Barry Norman told me during a visit to Aberdeen in 2013: “Powell and Pressburger could create the most wonderful films from the unlikeliest of source materials. Nothing worried them.

“In these days, almost all movies were shot exclusively in studios and only basic exterior shots and stock footage were used. But these two inventive men tore up the rule book. And I know they loved Scotland as well.”

No problems in making a whirlpool without CGI

The directors devised a complex scene at the heart of their love story, showing a small boat battling for survival amid the Corryvreckan whirlpool.

This involved a combination of footage shot at the actual site between the Hebridean islands of Scarba and Jura and Bealach a’Choin Glais (Sound of the Grey Dogs) between Scarba and Lunga.

A mixture of model work and technical trickery enhanced the sequence and Livesey’s scenes on Mull were depicted by a double. In lesser hands, it could have been a recipe for disaster, but the reception, both at the box office and from critics, was unanimous.

American author Raymond Chandler said: “I’ve never seen a picture which smelled of the wind and rain in quite this way, nor one which so beautifully exploited the kind of scenery people actually live with, rather than the kind which is commercialised.”

And Scorsese, the director of Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and numerous other classics, was even more laudatory. He said: “I reached the point of thinking there were no more masterpieces to discover until I saw I Know Where I’m Going.”

Wilder wasn’t wild about filming in Loch Ness

Not every Hollywood big-hitter drew inspiration from travelling to the north of Scotland. Billy Wilder, the director of such timeless classics as Some Like It Hot, Sunset Boulevard, Double Indemnity and The Apartment, was one of the greatest figures in the industry, with a stack of Oscars and other awards to his name.

Yet, when he and his colleagues decided to film parts of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in and around Loch Ness, they could hardly have imagined they would end up leaving a giant fake monster in the murky depths for more than 40 years, even as the underwhelming movie had scissors taken it to by studio executives.

When Wilder and his production team pitched up in the Highlands, they brought with them a giant 30-foot model of Nessie, designed by special effects artist, Wally Veevers, whose other work included 2001: A Space Odyssey, Superman and Local Hero.

Rogue prop caused numerous problems

But, despite strenuous efforts to make it convincing, and even allowing for the plot which stressed it was only being used to cover up the development of a new pre-First World War submarine by the Royal Navy, Veevers’ creation posed one problem after another – until finally, it disappeared under the waves.

Alec Mills was a camera operator on the second unit of the film and his son, Simon, told the Press and Journal about the travails faced by the film-makers with this rogue prop.

He said: “My dad was not long back from Portugal, where he had been filming (the James Bond movie) On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and, although I was only nine years old, I recall him telling me a few things about the ‘monster’ before it sank.

“Billy Wilder didn’t like its two humps and asked Wally Veevers to remove them, but unfortunately, these also contained hidden buoyancy aids and when it was towed out to the loch – by a Vickers submarine – it quickly rolled over and was gone.

“Alec’s involvement was more on the camera side than in the field of special effects, but I remember him saying they had filmed the ‘monster’ a few times prior to it sinking and that, through the camera viewfinder, it looked pretty unconvincing.”

It was a microcosm of the whole project, which sank without trace, and although there was global attention when the lost Nessie model was discovered in 2016, neither the film nor its soggy story were capable of redemption by that stage.

Shaken, not stirred in the Highlands

However, Wilder wasn’t the only man to encounter difficulties after bringing a major film initiative to the Highlands.

The James Bond films are probably the most famous franchise in showbusiness history, and there has been a close affinity between the producers and Scotland since they first emerged in the early 1960s.

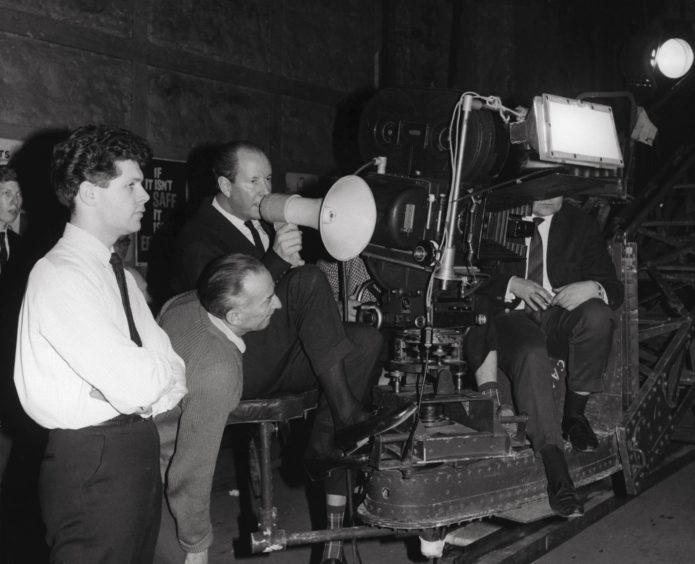

Yet, while Dr No screamed Yes Yes to the public and was a box office sensation, with the late Sean Connery starring as Ian Fleming’s muscular hero, a plethora of problems occurred behind the scenes during the filming of From Russia with Love.

These sparked havoc, both in Turkey, when the climactic and acclaimed boat chase sequence turned into a nerve-shredding drama of its own, and in Scotland, where several key members of the team were fortunate to avoid death.

While shooting on location at Kilmichall and off the coast of Crinan in Argyll, a series of potentially lethal accidents befell the crew. During one of the boat pursuits, the fireball from the exploding gas canisters almost turned into a full-scale conflagration and that is very real apprehension you can spot on the faces of the pursuing actors in the final edit.

A close shave with disaster

From Russia with Love director Terence Young nearly came to a sticky end in a helicopter as the whole venture threatened to go massively over budget.

In July 1963, while he was scouting locations in Argyll, Young’s craft crashed into the water and he was briefly trapped along with art director Michael White and a cameraman aboard the chopper.

It rapidly sank 40ft down into the water and Young was immersed in an air bubble as the situation worsened, despite his efforts to escape.

On another day, their desperate plight might have spelled tragedy and created grim real-life headlines, but the men held their nerve, wriggled free from their predicament and they all escaped with minor injuries.

Even more remarkably, despite these travails, Young was behind the camera for a full day’s work the following morning. He made light of what had happened earlier and later remarked: “You just had to get on with it.”

It was a sentiment with which Bond himself would surely have agreed.

Even Bette Davis couldn’t save Madame Sin

Many of the world’s biggest A-listers flourished as they cast their spell on movies created in the north of Scotland.

There’s Burt Lancaster in Local Hero, Liam Neeson in Rob Roy, Judi Dench in Mrs Brown, Mel Gibson in Braveheart – and also in Franco Zeffirelli’s Hamlet which was partially filmed at Dunnottar Castle. The list goes on and on.

But sadly, not even Bette Davis – the star of Now Voyager, All About Eve, Dark Victory, Jezebel and myriad other blockbusters – could rescue the thriller Madame Sin, when she travelled to Scotland and turned heads on Mull for several weeks in 1972.

The actress played the lead in the television film which was intended as a pilot for an upcoming ABC series with Robert Wagner, Denholm Elliott and Gordon Jackson.

But there are occasions when even Scotland at its most picturesque can’t save the day.

The movie bombed and Ms Davis – and her eyes, as immortalised in the Kim Carnes smash hit – was swiftly on a return flight to America.

Conversation