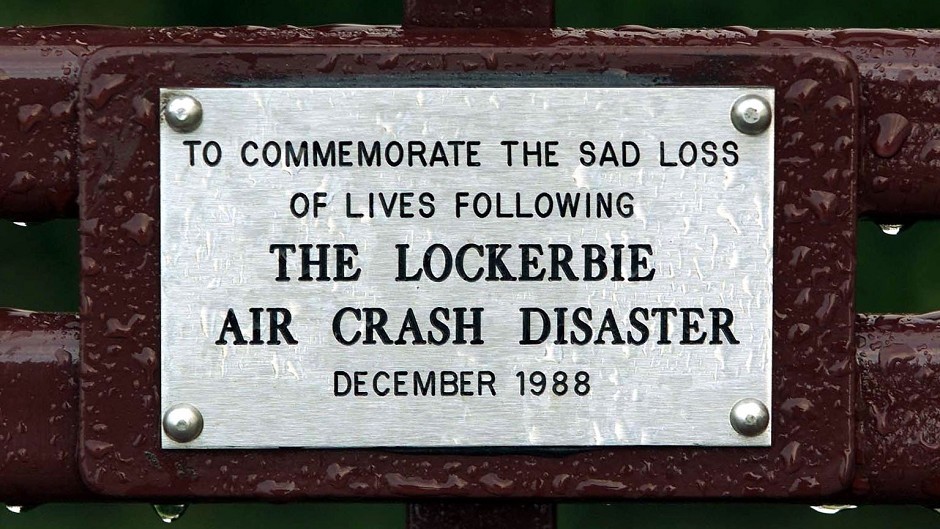

It was at just after 7pm on Wednesday, December 21 1988 when life changed irrevocably for the people of Lockerbie and the passengers and crew of Pan Am Flight 103 whose fates collided with devastating consequences.

Yet even now, more than 30 years later, the sights and sounds and the tear-stained, uncomprehending faces of those caught up in the worst act of terrorism on British soil remains painfully seared on my mind.

The following day, shock, horror, desolation and a desperate desire for answers as to what had happened were evident among the townspeople, 11 of whom were among the 270 who perished in the conflagration.

But the overriding impression for a journalist arriving at the scene was of a community numb with grief and loss.

One of the residents said simply after surveying the wreckage in Sherwood Crescent: “They were here one minute. Then they were gone.”

A decade later, I returned to Lockerbie and discovered that, although a veneer of normalcy had returned, allied to an impressive house rebuilding programme and the creation of new leisure facilities, the atrocity was still taking its toll.

This is one thing which those unfamiliar with disaster and tragedy may struggle to fathom, but the ripples extend way beyond the immediate impact.

New twist in United States offers hope of breakthrough

In the more than three decades since the atrocity occurred, just one man – Abdelbaset al-Megrahi – has been convicted in connection with the bombing.

He subsequently died from prostate cancer after controversially being allowed to return home on compassionate grounds to Libya, but many people, including the relatives of some of the families who lost loved ones, were never wholly convinced that Al-Megrahi was a major figure in the conspiracy which destroyed hundreds of lives.

However, it has emerged American prosecutors have released details of charges against a man they suspect of being a leading bomb-maker for the Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, and who allegedly assembled the device which blew up Pan Am 103.

The Justice Department is expected to unseal a criminal complaint against Abu Agila Mohammad Masud, who is currently being held by Libyan authorities, with a view to having him extradited to stand trial in the United States.

There have been so many twists and turns in the Lockerbie saga that the residents in the village will not easily be convinced all the perpetrators will ever be caught.

But they have never forgotten the terrible circumstances in which so many innocent people had their lives snatched away.

Flannigan family suffered irreparable loss

Just consider what happened to the Flannigan family and you will understand how Lockerbie was a waking nightmare for those concerned.

Kathleen Flannigan, 41, her husband, Thomas, 44, and their 10-year-old daughter, Joanne, were all killed instantly when an explosion ripped through their house at 16 Sherwood Crescent.

Their bodies were never found; they had quite literally been atomised in the blast.

In these circumstances, it is impossible to envisage the trauma which must have been experienced by their 14-year-old son, Steven, who witnessed a fireball engulfing his home from a neighbour’s garage, where he had been repairing his sister’s bicycle.

Their other son, David, 19, was in Blackpool at the time and was forced to return to a scene which was straight from a Dore painting.

He later turned to alcohol and drugs and died from heart failure in Thailand in 1993, aged just 24.

Steven, meanwhile, despite seeking a fresh start in England, couldn’t avoid being a prisoner of the past.

He died in August, 2000, struck by a train in Wiltshire.

A whole family devastated by what happened on that grievous December night.

Residents refuse to be defined by tragedy

It is hardly surprising that Lockerbie remains inextricably linked with something terrible, as does Dunblane, Hungerford, Aberfan…other little places which were thrust into the spotlight because of disaster and catastrophe.

But what impressed many of us who visited the town in the late 1990s was the determination of most members of the community not to be frozen in time, not to remain vengeful towards those who had perpetrated the attack.

Yes, conspiracy theories persist, but they are thin on the ground in Lockerbie.

As one resident told me: “We had to start again and find things to do to take our minds of it.

“But there were so many young people killed [including 35 students from Syracuse University] that we recognised others were a lot worse off than us.

“We knew their families would want to come here and try to make sense of what had happened. So we made up our minds to be there for them in whatever way we could.”

World will pay its respects as Christmas approaches

Next week, on the 32nd anniversary of the disaster, wreaths will be laid – albeit with social distancing – at a memorial garden in Lockerbie and a memorial ceremony will also be held at Syracuse University and Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, where a cairn made from Lockerbie stone stands in memory of those who died.

The residents, including the priest, Patrick Keegans, who was in the village when it happened, will never ever forget, but he wants to look forward as well as back.

As he said: “It doesn’t go away, it stays with people, especially those who have lost family. But it’s part of our life now. We live with it. We don’t live sad, miserable lives, but there’s a constant undercurrent. The memories stay with me, they are part and parcel of who I am now.”

At least, as he added, he was spared. So, too, was Kara Weipz from New Jersey, who lost her 20-year-old brother, Rick Monetti, one of the Syracuse students, whose dreams and ambitions were snatched away.

The mother-of-three, who is president of the Victims of Pan Am Flight 103 group, shares Mr Keegans’ feelings of tristesse, but she is also proud of the links which have been created and nurtured between the United States and Scotland.

Bonds forged between Scotland and the US

She said: “We can’t change things, we can’t bring them back, but we can look at the fact that we have always honoured them in the way we live our lives and the things we do.

“Yes, the sadness takes many forms, but myself and others are also looking at what we’ have done in the last 30 years and how we have come together, enacted change, created our own family, and been there for one another.”

There may or may not be something tangible to emerge from the latest developments by the Justice Department, but it will not change the links forged between those who lived and died and their relatives and descendants from America and Scotland.

If there is any positive aspect to Lockerbie’s suffering, it surely lies in that abiding connection between two countries and hundreds of families.