It was a year when many festivals and ceremonial events had to be cancelled because of Covid-19.

Large-scale commemorations of such milestones as the 75th anniversary of VE and VJ Day in June and August were scrapped with smaller-scale events staged remotely and the same restrictions applied to Remembrance Day in November.

It has also been difficult for families to arrange funerals for their loved ones, while many well-known north and north-east figures from different worlds, whether in the secretive domain of Bletchley Park, the tumult of the D-Day landings and the Battle of El Alamein, or the mountain wilderness of the Himalayas, have left us during 2020.

Here, as we move towards the New Year, is a celebration of some of the extraordinary and idiosyncratic people who died during the last 12 months.

Jimmy Sinclair (1912-2020)

He was the last of the Desert Rats who fought with tremendous courage in North Africa during the Second World war.

But, just a few weeks after his bravery was celebrated on the 75th anniversary of VE Day, Monifieth-based Jimmy Sinclair died in May at the grand old age of 107.

Almost to the end, the Fifer never lost his ‘joie de vivre’ or determination to find the positives in any situation and still enjoyed a dram of whisky and a bowl of porridge.

Mr Sinclair entered the world in 1912: the same year that the Titanic made its ill-fated maiden voyage and when Herbert Asquith was in Downing Street.

He was a widowed father of two and grandfather of three, who received regular letters and photographs from Camilla, Duchess of Rothesay, and he talked vividly about the sacrifice on both sides during the battle for Tobruk, which lasted for 241 days.

Life amid the chocolate-stealing rats in the sand

He explained later why he and his comrades became known as the Desert Rats.

He said: “One day, we were in the NAAFI and were living in a sandbank dug-out and I put a piece of chocolate in the palm of my hand and showed it to my mate.

“I said: ‘Come and see this’.

“And then, a rat came out between the sand bags and took the chocolate and went back in. There was a real desert rat on the palm of my hand.

“Then, on another occasion, I woke up to find a rat chewing my ear!”

Two years later, after he had been re-deployed at Monte Cassino, he was badly burned and spent eight weeks in an Italian hospital, where he found himself becoming the driver for Hugo Baring of Baring Bank fame.

A larger-than-life character, who became friends with former enemies, and enjoyed a “wee whisky” well into his 11th decade, Jimmy was loved by all who knew him.

HELENE ALDWINCKLE (1920-2020)

She was just 21 when she was recruited from Aberdeen University to join the crucial work which was being done at Bletchley Park during the Second World War.

And former codebreaker Helene Aldwinkle was presented with the insignia of Knight of the Legion d’Honneur – France’s highest civilian and military honour – just a year before her death in April this year aged 99.

Back in 1942, the young Helene Taylor left Scotland for only the third time in her life, travelled to a place she did not know and lived with complete strangers, to do work which she could not even be told about until after she had arrived.

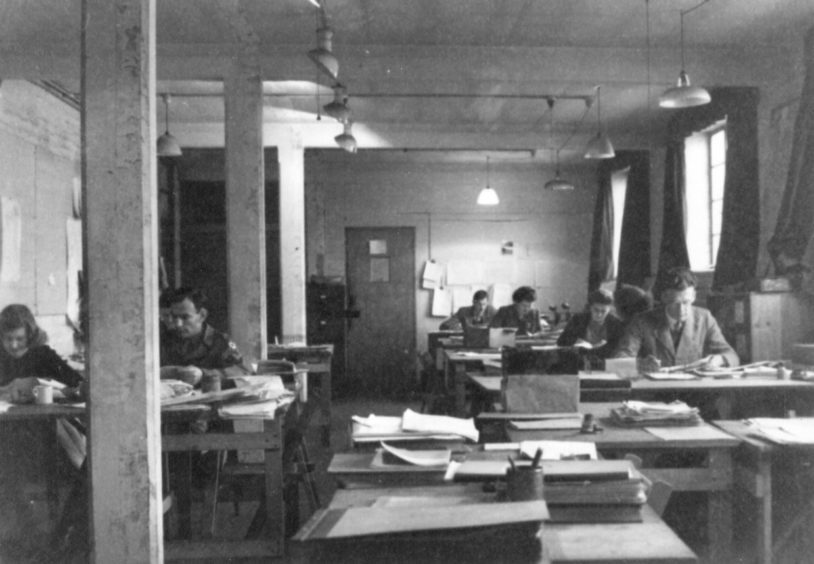

She was chosen by a senior codebreaker, Stuart Milner-Barry, to work in Bletchley Park’s Hut 6, the department tasked with deciphering Enigma messages sent by the German army and air force.

In doing so, she played an important part in cementing the British-American intelligence sharing agreement which endures to this day.

From 1944 until the end of the war, this resilient individual worked in a section of Hut 6 called the Quiet Room, where she identified the various Enigma radio networks, and analysed radio signals’ preambles and sign-offs.

Hut 6 played a crucial role in the lead-up to the Normandy invasion and, more than 70 years later, the French Republic honoured Mrs Aldwinkle for her contribution towards D-Day and the liberation of France.

ERIC JOHNSTON (1923-2020)

There was a time in 1942 when the outcome of the Second World War hung in the balance.

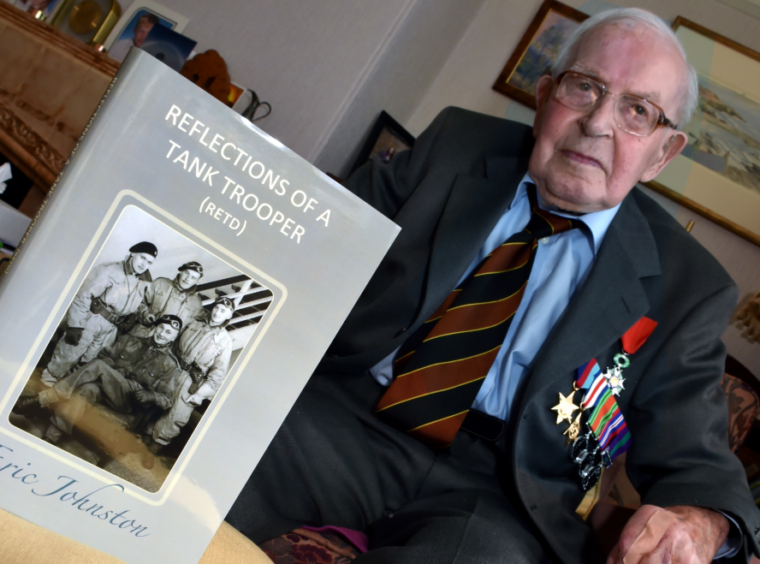

But Aberdeen’s Eric Johnston was one of the people who made a difference in the conflict and moved from being a bank employee to winning the Legion D’honneur and being a pivotal figure during the D-Day landings in Normandy in 1944.

Mr Johnston left his parents, George and Isabella, disconsolate when he decided to become a tank driver and a reconnaissance trooper with the Royal Dragoon Guards.

He became one of the heroic figures in the preparation and implementation of D-Day, although Mr Johnston, who died in January, aged 96, was very critical of the manner in which hundreds of American troops died on their way to Normandy.

A fiercely single-minded character, he decided to record his memoirs in a book – which he wrote in his 90s – called Reflections of a Tank Trooper (Retd).

‘You won’t be around forever, you know’

The last word was typical of his approach to dealing with any setbacks. As he told me during one of our meetings at his Aberdeen home: “I was at a reunion and I mentioned some of my war memories to a friend.

“He said: ‘You better put them down on paper. You won’t be around forever, you know’.

“So I went home and started writing the book the very next day.”

Mr Johnston – a keen mountaineer who also loved rugby – was the subject of one of 12 portraits, commissioned by Prince Charles, to honour D-Day veterans in 2015.

He attended the unveiling of the paintings of veterans at Buckingham Palace with his daughters, Helen and Sheila, and met the Duchess of Cornwall.

HAMISH MacINNES (1930-2020)

Hamish MacInnes, one of the world’s most famous mountaineers, died at his Highland home in November, aged 90.

The remarkable Scot, with the nickname The Fox of Glencoe, who was climbing on the Matterhorn as a teenager and was involved in Sir Chris Bonington’s successful Mount Everest Southwest Face expedition in 1975, was a pioneering figure widely regarded as the father of modern mountain rescue.

His inventive mind was the catalyst for a number of initiatives such as the Search and Rescue Dog Association and the Avalanche Information Service.

He made an attempt to climb Everest in 1953 and invented the first all-metal ice-axe and a lightweight stretcher, widely used in mountain and helicopter rescue.

During his far-travelled and eventful life, he worked with some of Hollywood’s biggest names, including Clint Eastwood, Sir Sean Connery and Robert De Niro on such films as The Eiger Sanction, Five Days One Summer and the Mission.

Hamish rallied from problems in old age

A pioneering free spirit, he built his own motor car when he was just 17. There were few problems which confronted him, on or off the peaks, whch he could not negotiate. Or, at least, not until the latter stages of his life.

In 2014, Mr MacInnes suffered a urinary tract infection which left him suffering from delirium and he was ‘sectioned’ into a psychiatric hospital in the Scottish Highlands.

Eventually, after recovering from the illness, he was left with no memory of his former life but rallied from adversity and made a poignant return to the spotlight.

As some colleagues said, the mountains will seem emptier without him.

JACK WEBSTER (1931-2020)

He was the prolific north-east journalist who ghosted a newspaper column for the legendary Muhammad Ali, secured a world exclusive interview with Charlie Chaplin in Banchory and was friends with Bing Crosby.

Jack Webster, who died in March aged 88, was told early in his life after being diagnosed with a leaking heart valve that he should settle for a job as a bank clerk.

But the Maud-born farmer’s son proved the doctors wrong and spent the next 60 years defying obstacles – from overcoming a stammer to be crowned UK Speaker of the Year in 1996, to trumping his rivals by gaining access to all manner of international figures, including Elizabeth Taylor, Sophia Loren, Ginger Rodgers, Pele and George Best.

He also landed a genuine scoop with comic great Chaplin at the Tivoli in Aberdeen.

Jousting with giants without losing his north-east passion

Mr Webster’s journalistic career, honed on a passion for Sunset Song author, Lewis Grassic Gibbon, started at the Turriff Advertiser before 10 years at the Press and Journal. He then moved to Glasgow and joined the Daily Express.

While there, he became the Scottish equivalent of Michael Parkinson, securing interviews with many of the biggest stars of stage and screen.

One of his sons, Geoff recalled: “Dad was given a roving role and he managed to set up some remarkable meetings with the likes of Chaplin and Ali.

“He learned that the former – who had refused to speak to journalists after being hounded out of America – was staying in Banchory. So he checked into the same hotel, got talking to the great man and asked if he would like to revisit the Tivoli, where Chaplin has performed early in his career. He said yes.”

BUFF HARDIE (1931-2020)

There were no airs and graces about Buff Hardie, even as he was creating the mystical world of Auchterturra and enjoying success with Scotland the What?

He and his colleagues, Steve Robertson and George Donald, may have become showbusiness luminaries and been showered with accolades including the rarely-bestowed Freedom of Aberdeen in 2008, but Mr Hardie, who died earlier this month aged 89, never forgot his roots or growing up at 90 Hilton Road in his home city.

In his “real” job, Mr Hardie, who advanced from a north-east childhood to graduating from Cambridge University, expressed his desire to help others and for many years, he was the secretary of the former Grampian Health Board which, among other things, helped design the current Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

However, his life was transformed when the Scotland the What? show earned glowing reviews from the critics, was lapped by by an international audience, and they subsequently became successful performers whenever they unveiled their latest work at their spiritual home, His Majesty’s Theatre, in Aberdeen.

Neville Garden was ready to laugh at anything

He told the Press and Journal, just a few weeks before his death: “We performed at the Fringe in a small church hall with an hour-long show and our pitch was: ‘Three men, two chairs, one piano – and the promise that you won’t leave without laughing. One of the first people who saw us was Neville Garden, who had just sat through four hours of Wagner at the Usher Hall and was ready to laugh at anything – which he did.

“The next day, his crit in the paper declared he had just seen ‘the funniest show in the festival’ and the whole thing took off. We never looked back.”

Thereafter, the group devised new sketches and musical numbers every two years, which they unveiled to packed audiences at HMT, before taking their routines on tour around Scotland and to other parts of the world.

And although their last hurrah was in November 1995, they received the Freedom of Aberdeen from the city council for “their services to the fine arts, the Doric language and North East of Scotland culture; and, above all, for makin’ a’body laugh.”