If the answer is 42, what was the question?

Well done you at the back shouting: “What’s the meaning of life, the universe and everything?”

That, though, is not the answer – although 2021 does mark 42 years since Douglas Adam’s genius novelisation of the radio show, The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, was published.

But it is also 42 years since I walked into a newsroom in the first week of January 1979 and became a working journalist.

By which I mean, I stumbled down the steps of the editorial hall of the Evening News in Edinburgh, a clumsy, naïve 17-year-old with my head filled with idealistic notions of becoming the next Bob Woodward or Carl Bernstein (my modern studies class had included a cinema trip to see All The President’s Men).

Now I was presented with the reality of a working newspaper… a fog of smoke hung over every desk, typewriters were clattering, people were shouting “copy”, phones were ringing loudly, there were booming conversations and telephone interviews going on everywhere. It was as far removed from the quiet of a modern studies classroom as you could imagine. I loved it.

It confirmed my decision that university wasn’t for me. I wanted to be a journalist – I liked writing, I was nosey and I wanted to interview Sean Connery – and the best way to do that was go and be one.

That first day was merely an induction as a trainee reporter, the start of my three-year apprenticeship into the craft of journalism – I signed indentured papers and everything.

My inaugural whistle-stop tour of the rabbit warrant that was The Scotsman building took in the case room, where a jigsaw puzzle of pages were put together before being sent to the press.

I was given a stern lecture by my deputy editor and a guide to put my hands behind my back and touch nothing while I was in there.

We are talking of the days of union demarcation where if I were to so much as pick up a ruler out of curiosity as to ask what a line gauge was, I could spark a walkout.

There were the Linotype machines, where grizzled veterans, fags in the corner of their mouth, seemed to work magic on a giant typewriter turning molten lead into golden prose, ready to be plated for the massive presses.

I was introduced to the concept of a stone sub. This was a journalist who had to make last minute tweaks to pages to sort out copy that didn’t fit or fix anything he found wrong, all while the lead slugs were being loaded into a galley by a skilled compositor. Said journo had to stay on his side of the composing stone and touch nothing (see demarcation above) while being able to read back to front and upside down. I was in awe.

Oh and the press itself. A thing of wonder then and today, an intricate web of paper and ink that seemed to roar all around a cavernous hall, the floor vibrating, before spewing out papers at the far end, ready to be bundled into vans and off to newsagents across the Lothians.

This was the tail-end of the long-gone era of hot metal newspapers… and a bit of an eye-opener for a boy thinking he was entering a slick, hi-tech world. I remember sitting at a desk and looking quizzically at the typewriter in front of me before asking why it had glass panels in the sides. “Well, son, you see… there was a shortage of metal during the war.”

My first day ended as it did for most hacks in the 70s… in the Halfway House pub just across from the back door. That I was only 17 didn’t matter a jot. And within minutes I had earned my hack nickname. Half-pint Begbie. I blame the tricky Fleshmarket Close steps.

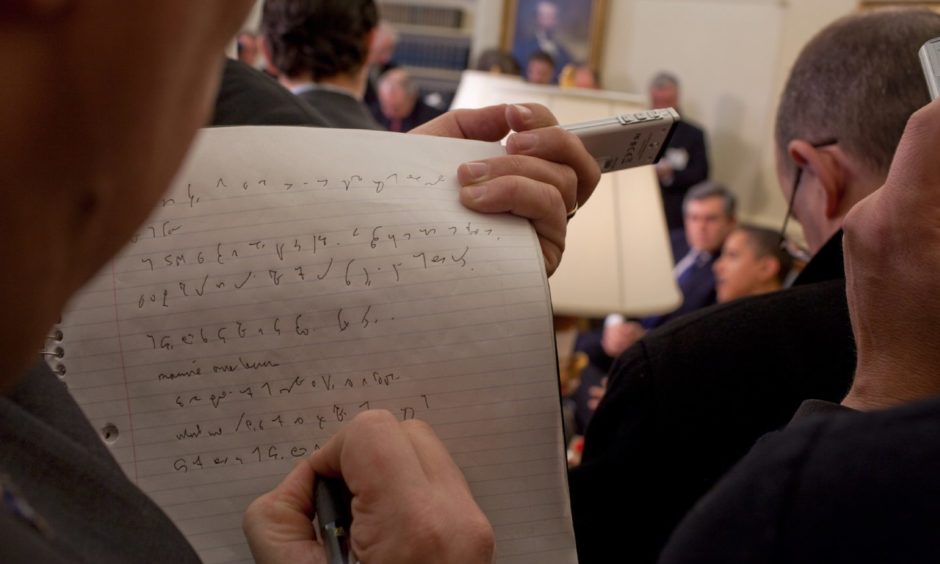

I wasn’t to see the inside of the Evening News for six months after that. I was despatched to a training centre in Newcastle to learn the basic skills to turn me into a newshound – how to write news stories, how to structure features, law for journalists, how to report on councils, and shorthand. The latter was my bête noire.

I have always had atrocious handwriting. Trying to keep things legible is a laborious task for me, although if I give in and just scrawl, I can’t even read what I’ve written myself. Learning shorthand didn’t help. Thank goodness for keyboards and touch-typing, that’s all I can say.

I did manage to get the shorthand speeds I needed, with a combination of Teeline and developing an excellent memory for dialogue, that allowed me to fill in the blanks when I transcribed my notes as soon as I had finished interviewing someone.

But I learned so much in those six months in Newcastle, becoming a bit more worldly-wise on the way. Let’s just say I was so unaware of the way that things worked I was astonished I was going to have to pay for digs in Whitley Bay as opposed to someone just putting me up out the kindness of their heart.

I also discovered what the phrase “cavalier” meant, when my end-of-term report referred to my approach to spelling – a foible since, largely, fixed.

1979 was a heady time to be entering the world of newspapers. Just take a look at what happened in the six months I was in Newcastle from January to June.

In January Prime Minister James Callaghan uttered the immortal phrase: “Crisis, what crisis?” at the height of the Winter of Discontent, a series of national strikes that saw rubbish left on the streets and burials postponed.

In February, Sid Vicious was found dead in New Yok.

In March, the devolution referendum saw a majority vote in favour of a Scottish Assembly, only to be scuppered by the pernicious clause that 40% of the electorate had to support the idea. The same month, Callaghan’s government lost a motion of confidence forcing a general election.

In April, the Yorkshire Ripper claimed another victim, 19-year-old bank worker Josephine Whittaker.

In May, Margaret Thatcher won the general election to become the United Kingdom’s first female Prime Minister and all that followed.

So when I went back to the Evening News to become a trainee reporter proper, it was into a time of massive change in politics, society and, eventually, journalism.

The three years until I qualified was rough and tumble stuff. The edges were knocked off you quickly and, at times, brutally by senior editors.

If you made a mistake, you knew about it, with no niceties involved. I was once told to go away and consider my future for three days, essentially suspended, for misusing an apostrophe for the second time in two days. I know now how apostrophes work.

If your copy wasn’t up to par, you were told in no uncertain terms – usually Anglo-Saxon.

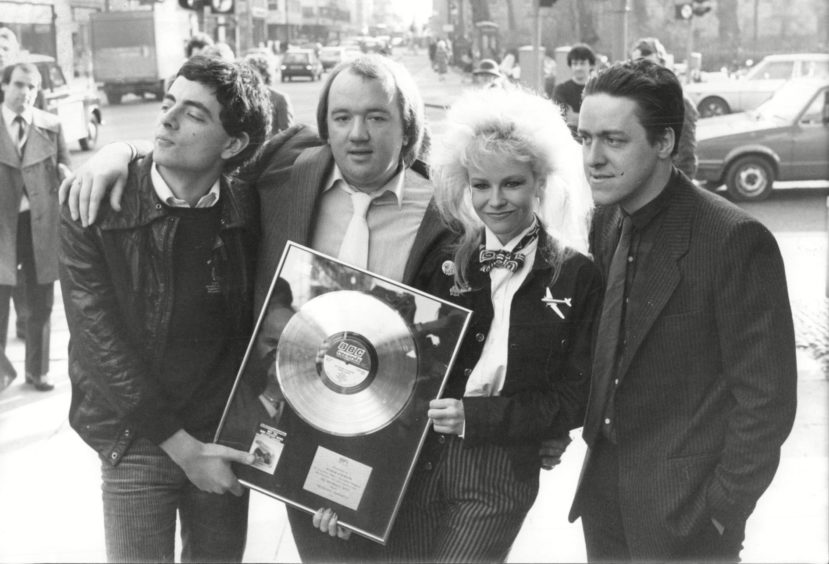

As an unworldly teenager, it was also an awakening to the realities of life in 1970s and early 1980s Edinburgh, from its dark underbelly as drugs took a grip on schemes, to the glittering world of showbusiness and the arts courtesy of the Fringe. One day you were reporting on a drugs raid in Pilton, the next you were interviewing Griff Rhys Jones, at the height of his Not The Nine O’Clock News fame, about his one-man show in the festival and reviewing Rowan Atkinson’s gig the same night.

It was a macho world full of big, uncompromising, unapologetic characters, where you had to develop a thick skin, learn fast and play hard.

It was the best training I could have had. It instilled in me three things. The basics of my craft, a love for it undiminished to this day and a gratitude for all the things it has shown me and allowed me to do and to be.

Which is why I am vaguely astonished that more than four decades on it still feels like yesterday since I started this malarkey. But they do say time flies by when you are enjoying yourself.