When the bells ushered in the New Year in 1901, Queen Victoria had been on the throne for so long that hardly anyone could remember a time when she wasn’t the ruling monarch of the far-flung British Empire.

Thus, when the news emerged of her death on the Isle of Wight on January 22, it’s perhaps hardly surprising it was greeted with a mixture of grief, consternation and near panic among the ruling class.

At first, some people refused to believe she had gone after 63 years in the role during which time she met 10 prime ministers and 18 US presidents, but those closest to the Queen had witnessed her gradual decline in previous months and sensed the worst.

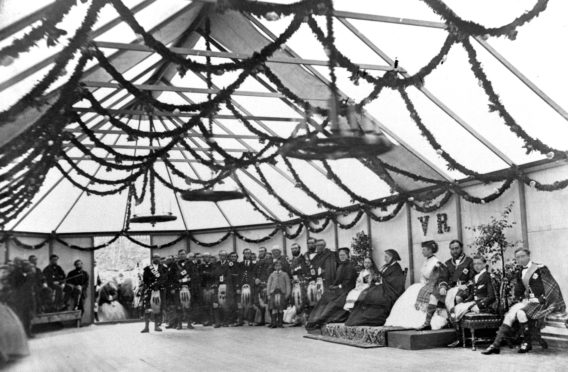

And nowhere was this more obvious than at Balmoral, one of Victoria’s most treasured places of sanctuary and solace in the whole world.

Indeed, her final visit to the north-east of Scotland in October 1900 was marked by the loss of a family member thousands of miles away which plunged her into a spiral of melancholy and led to her leaving the castle with tears in her eyes.

Even the presence of her devoted Ellon-born doctor, Sir James Reid, couldn’t provide a stimulus to his most important patient.

As the Aberdeen Journal reported the following January: “Not a few of the servants were afraid this would be the last time that they saw the Queen at Balmoral.

“It was a presentiment which has, sadly, been fulfilled.”

Another death reduced the Queen to melancholy

The monarch had already lost many of her most cherished family members, friends and loyal retainers by the start of the 20th century.

She was also suffering from such conditions as dyspepsia and aphasia, but derived comfort from her conversations with Reid, which varied from “whether dogs had souls and an after-life” to her “hatred” of the former Liberal premier William Gladstone.

However, shortly after they arrived at Balmoral, the Queen was plunged into profound grief upon learning about the death of her grandson Prince Christian Victor of Schleswig Holstein, who had succumbed to malaria and enteric fever in South Africa.

The Aberdeen Journal said: “Her Majesty was stricken by this news and, a day later, it was officially announced that her departure from Balmoral had been brought forward by three days.

“But, on November 1, she attended a memorial service in Crathie Church [Kirk] for the lamented Prince, where she was deeply moved by the solemn proceedings”.

Yet, on the very next day, even as the monarch was striving to rally from the impact of the tragedy, she suffered another ghastly blow.

A letter was delivered for her attention and she immediately recognised the handwriting. After it had been opened, she read the correspondence from none other than Prince Christian, who had sent off the missive before falling gravely ill.

The royal party had never left Balmoral in such sadness

He talked about how much he was looking forward to returning to Europe and visiting her in Britain – and, in many respects, it was the last straw for the 81-year-old.

The Journal explained: “Her Majesty’s grief on receipt of the letter was poignant and painful and the words left her feeling disconsolate.

“Sir James Reid, who had left a day previously to visit relatives in Buchan, was telegraphed for and hastened back to Balmoral and he travelled on a special train from Aberdeen to Ballater.

“On November 6, the Court left Balmoral and never before in all the past years had her departure taken place in such sad circumstances.

“She was unable to make her customary visits to her old servants and retainers and, even as she left, she was distressed and in tears.”

Her courtiers could discern the pain and weariness in her eyes. Many of them privately accepted they were unlikely to see her in Scotland again. And they were right.

The last few weeks were filled with pathos

Sir James Reid has started to accept there was little he could do beyond providing care to the Queen and indicating to her family that they might have to prepare for a future without her.

Sadly, none of them could contemplate the mortality of the old lady who had sat on the throne since 1837 and become inextricably linked with stability and assurance.

Her children were in denial about her condition, her government was unprepared for dramatic constitutional change, and most of the public – though not those working at Balmoral – knew nothing about her deteriorating health and morale.

Victoria’s own view of the future was bleak as she conveyed early in January: “Another year has begun, but I am feeling so weak and unwell that I enter upon it sadly.”

Just over three weeks later, shortly after 6.30pm on Tuesday January 22, Superintendent Fraser ordered the household police to surround the queen’s Isle of Wight residence at Osborne House.

The press reported: “All telephone and telegraph wires were to be suspended, and any servant or messenger was to be prevented from leaving.

“A short while later, he walked down the long gravel drive to the entrance gate where a large crowd was waiting, and pinned a small notice on to the bulletin board.

The message was stark: “Her Majesty the Queen breathed her last at 6.30pm, surrounded by her children and grand-children.”

Soldiers were sent to London from all over Britain

It was terse and to the point, but the news had been announced to the world.

It was met with chaos and confusion and grown men and women weeping in the streets from Liverpool to London and Aberdeen to Abergavenny.

The London Evening News had a black-bordered special edition out on the street within the hour. Theatre performances were interrupted as audiences poured out into the streets and the Great Tom bell of St Paul’s tolled across the city of London.

Across the nation, people gathered in small groups to sing God Save the Queen, even as the realisation sank in that the long Victorian era was over.

There was no one alive who could remember the meticulous process of organising such a grand occasion as a full military state funeral.

More than 30,000 soldiers were sent to London.

But, in the next few days, in accordance with the late monarch’s wishes that she wanted no black worn at the service and the ceremony should be appropriate to “a soldier’s daughter”, detailed plans were drawn up for what became one of the biggest commemorations in British history.

Sir James Reid, the queen’s personal physician for more than 20 years, had known the end was nigh, but had great difficulty convincing the royal family of the inevitable, even in the final days when they saw the queen was drifting between delirium and lucidity.

Yet, once her death had been confirmed, matters changed.

Soldiers from all over Britain, including those serving with the Gordon Highlanders in the north-east of Scotland, were sent to London and became involved in organising a vast logistical operation; one which involved representatives from across the world travelling to Britain for the funeral service at the beginning of February.

Newspapers covered the event with screeds of information

The British press covered their pages with information about the funeral, while reflecting on the late Queen’s legacy and looking back at her unprecedented reign; a period spanning seven decades which coincided with seismic shifts in society, allied to the creation of a whole set of “Victorian values”.

Her body was taken on to London, with Sir James Reid involved at every stage. He, after all, was one of the few individuals she regarded as a confidant and it was the Scot who oversaw such matters as dressing the body in white and allowing the staff to lay keepsakes and mementoes in her coffin, including those of her late husband, Prince Albert and John Brown, her trusted ghillie at Balmoral.

Some eyebrows might have been raised in the royal household at Brown being remembered in this fashion 18 years after his death, but the Queen was determined to demonstrate her exalted opinion of the Scot, who was born in Deeside in 1826.

As she said at the time of his death in 1883: “He had no thought but for me, my welfare, my comfort, my safety, my happiness.

“He was courageous, unselfish, totally disinterested, discreet to the highest degree, speaking the truth fearlessly and telling me what he thought and considered to be just and right without flattery.

“The comfort of my daily life is gone. The void is terrible, the loss is irreparable!”

The funeral saw thousands of people thronging to London

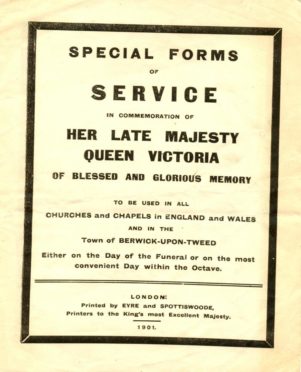

The state funeral of Queen Victoria took place on February 2 1901; it had been 64 years since the last burial of a monarch, so it was very different from previous services.

Victoria left strict instructions regarding the arrangements and associated ceremonies and instituted a number of changes, several of which set a precedent for state (and indeed ceremonial) funerals which have taken place since.

First, she disliked the preponderance of funereal black and requested a white pall for her coffin. Secondly, she expressed a desire to be buried as “a soldier’s daughter”.

She had also requested there should be no public lying in state and no burial in Westminster Abbey – where so many other kings and queens had been interred – so her body was conveyed by boat and train to Waterloo Station, then by gun carriage to Paddington Station and by train to Windsor for the funeral service itself.

Everything testified to the nation’s sorrow

The rare sight of a state funeral cortege travelling by ship provided a striking spectacle for the crowds: the late Queen’s body was carried on board HMY Alberta from Cowes to Gosport with a fleet of yachts following it, one of which was carrying the new king, Edward VII, and other mourners.

Minute guns were fired by the assembled vessels as the yacht passed them by. Victoria’s body remained on board the ship overnight, prior to being conveyed by gun carriage to the railway station the following day for the train journey to London.

Her children had married into the great royal families of Europe and a number of foreign monarchs were in attendance, including Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany and the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

As The Times reported on February 4: “The signs of mourning were universal. The houses were shrouded in purple hangings and the people clad in the profoundest black.

“The demeanour of the crowds was markedly subdued and respectful. And everything betokened the heartfelt sorrow which is felt by all classes of society.”

The funeral did not pass without a hitch, most notably at Windsor where the horses who were pulling the gun carriage became agitated and flustered and almost sparked a stampede, as the prelude to being replaced by sailors.

But, in every other respect, this was a dignified, poignant ceremony of remembrance for a remarkable woman.

The Gordon Highlanders ‘looked exceedingly well’

A number of 3rd Battalion Gordon Highlanders formed up as representatives of the Militia, along with 3rd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, 4th Royal Irish Regiment and 4th Battalion Norfolk Regiment.

According to the Aberdeen People’s Journal on February 9 1901: “There were four companies belonging to the different militia regiments, and of these by far the most effective were the men from the 3rd Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders.

“With their dark green kilts and their white spats and their fine bearing, they looked exceedingly well.

3rd Battalion Gordon Highlanders were previously known as the Royal Aberdeenshire Highlanders and was a Militia regiment raised in 1798.

Aides-de-Camp were also part of the mourners and among the assemblage of men was a Gordon Highlander, Colonel Henry H Mathias.

This distinguished soldier served as aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria and then to King Edward from 1898 to 1907. He entered the 75th (Stirlingshire) Regiment in 1869 and rose through the ranks, rising to the rank of lieutenant-colonel.