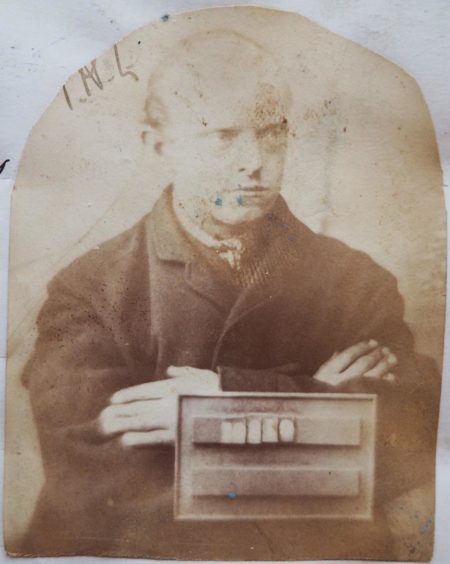

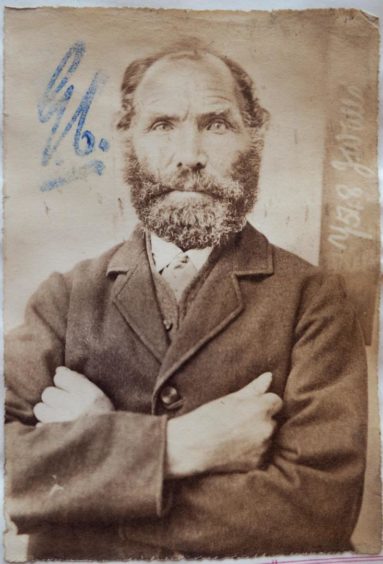

The gaze holds you… the piercing stare of a Victorian criminal reaching across more than 150 years from the instant in time their prison mugshot was taken.

But who was this man in the sepia photo? What was this woman’s crime? What was their life in Victorian Aberdeen like? Was their time in prison truly hellish?

These are all questions Phil Astley, Aberdeen City archivist, aims to answer in a key event as part of Granite Noir, the city’s crime-writing festival, taking place online next weekend.

He will be delving into the lives and crimes of five people, getting behind the fascinating mugshots held in the city’s records to create a compelling insight into who they truly were.

“People respond to the mugshots because of the direct stare these people give the camera,” said Phil, whose webinar Criminal Portraits: A Closer Look will be held on Sunday February 21.

“In some of the pictures the people are really fixing you with quite a steely stare. You can tell quite a lot about the character of the person from the images, or you think you can.

“The images make for fascinating glimpses of people’s lives and in the sense of Granite Noir they are absolutely ideal for a crime writing festival. They give you some of the story, but you can fill in the story through your imagination and additional research.”

Fluttered from one crime to the next

Phil has chosen five mugshots to explore, drawing on contemporary records, census returns and newspaper reports to bring them to life for a 21st century audience for his event, which builds on his popular online blog, Criminal Portraits.

“I want to put these people and their crimes in some kind of context, looking in a little more detail about the Aberdeen of the time and looking at their incarceration and what they would have gone through there.”

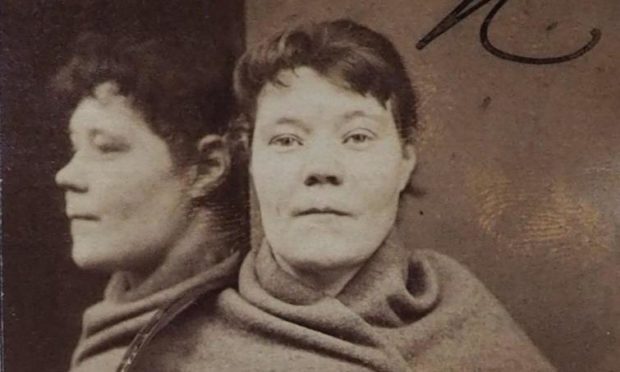

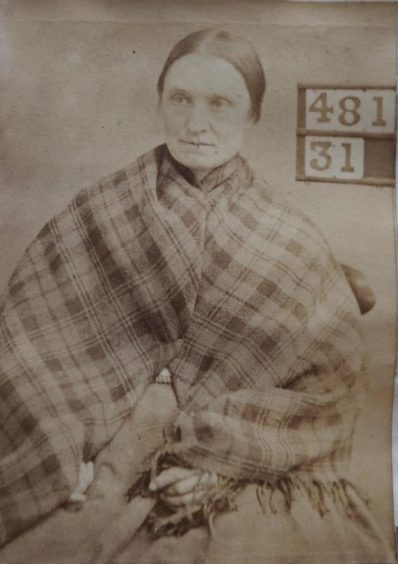

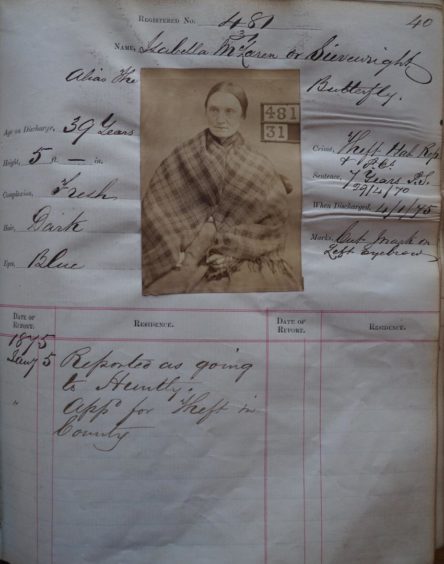

One of three women and two men Phil will put into the spotlight during his webinar on Sunday February 21 will be Isabella McLaren or Sievewright.

She was known as The Butterfly from Turriff, so-called because she fluttered from one crime to the next, mostly petty theft, but she was also a prostitute.

“She appears in the 1871 census for Perth Prison and is a notorious character and she created quite a scene in court and attacked one of the witnesses.”

She seized the unfortunate witness with both hands by the whiskers and tugged away fiercely”

The Aberdeen Free press reported the incident saying: “She seized the unfortunate witness with both hands by the whiskers and tugged away fiercely”. She also pulled handfuls of hair from his head “stamping with positive rage and fury” before police pulled her away.

Phil said: “She was well known to the police, but ironically her husband was listed as a carter for the police, so he was actually employed by the police in the early 1860s. But he was a bigamist. (Isabella) has this really colourful and sad life. She dies by drowning in Peterhead Harbour in the early 1890s.”

Another female convict under the spotlight will be Ann McGovern. She was an Irish immigrant who came to Glasgow after the potato famine, before working her way towards Aberdeen in the 1870s.

Phil said: “She was an interesting character, she was probably what we could call a Traveller. Her occupation in the census returns was a hawker, which implies a transient lifestyle, moving from one place to the next, selling anything she can get her hands on.

Her address was given as the Victoria Lodging House when she was released… that is Provost Skene’s House. “

“Her address was given as the Victoria Lodging House when she was initially released from prison. That is Provost Skene’s House. Quite a number of the prisoners give that address. It’s essentially a doss house.”

Ann’s photograph first appeared in records in 1871, then again in another album of mugshots 10 years later.

Sentences became gradually heavier

Phil said: “She was convicted of petty theft, but the reason she ended up in prison was because she was what was called a habit and repute thief. If they end up in court or are tried on a number of occasions, the sentences gradually become heavier.”

In Ann’s case, she was sentenced in 1865 to 30 days for stealing a pair of ladies’ boots, but in 1868 she was sent down for seven years for a theft in Aberdeen.

“The crime in itself probably wasn’t very much,” said Phil. “But it’s the accumulative effect of it.”

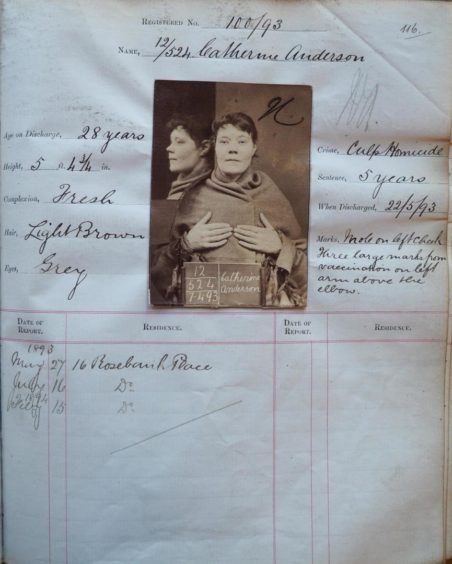

The final woman in the infamous five is Catherine Anderson, who was tried twice for infanticide in the 1880s. She also had two children who survived.

Men are also in the mix, with James Walls and David Todd.

It’s quite interesting to compare knife crime these days to what this guy went through”

Phil’s interest in Walls stems from the fact he possibly had scrofula, a form of TB, and prison reports shed light on how such ailments were treated behind bars in the late 1800s.

Todd, meanwhile, was tried for murder but was sentenced for culpable homicide. Phil said: “There was some element of doubt as to whether it was premeditated. He was carrying a weapon, but it’s quite interesting to compare knife crime these days to what this guy went through.”

Todd stabbed and killed James Watson on Castle Terrace in 1870, but pleaded he was acting in self-defence as Watson was the aggressor. He was sentenced to seven years – which is what some petty thieves of the day were being handed.

Phil’s extensive research stems from the Register of Returned Convicts for Aberdeen, a record started in 1869 of those who had spent time in jail – including around 61 mugshots. It was used so habitual offenders could be better tracked by the authorities as they made their way back into society.

The city archives and its crime records have been involved with Granite Noir since the festival began and its exhibitions have been hugely popular.

Public really responded to mugshots

“We’ve always drawn quite heavily on the Grampian Police records we have, which contain a number of different things,” said Phil. “We’ve had an exhibition of wanted posters, last year we did one on women in crime and the year before that it was completely devoted to mugshots. The year prior to that, we had an exhibition of crime scene photos.

“But every year we have included the mugshots it has been really obvious that the public have really responded to these.”

The newspapers of the time are a goldmine as the trials are reported in staggering detail”

It was for that reason Phil started his own blog, Criminal Portraits about a year ago with the aim of filling in the “scanty details” behind the images and records.

“I wanted to dig deeper, to try and find out more about these people. In pretty much every case, I have managed to flesh out their stories. The newspapers of the time are a goldmine as the trials are reported in staggering detail. Some of the comments made about the individuals are quite derogatory, but they add that kind of colour you don’t get in this day and age.”

The webinar on February 21 will build on that research and offer an insight not just into the villains Phil has chosen to feature, but also conditions in society and prison at the time

It promises to lift the curtain on conditions for inmates at a time when Perth was the general prison in Scotland, before Aberdeen’s own Craiginches was built in 1891. It was in Perth most of the early mugshots were taken, though some were from Ayr prison. There is also a record of one Aberdeen prisoner sent to Pentonville in England because of the pressure of space on Scottish jails.

I think it would have become incredibly

monotonous after the first week or two”

“It was fairly common for them to go to prisons in England,” said Phil. “Of course in this day and age, when proximity to family and visiting rights is very much something that is thought of, the mind boggles at how far away from Aberdeen and Scotland these people were in some cases.”

Life in prison was grim

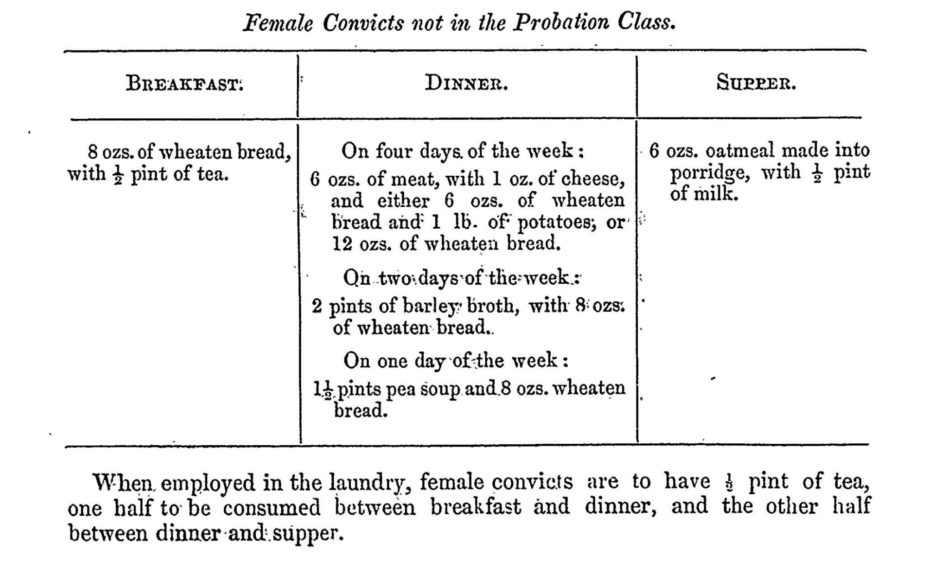

Clues as to life in prison can be found from contemporary reports from the governors of the prisons in the late 1870s.

“You can pick up information about the diet of the prisoners, which is pretty grim,” said Phil.

The litany of meals for female convicts ranged from 8oz of bread with a half-pint of tea for breakfast, to dinner mostly comprising of 6oz of meat and an ounce of cheese and 6oz of bread plus a pound of potatoes. Two days a week dinner was barley broth with bread. One day a week it was pea soup for dinner. Supper was always porridge. The diet didn’t vary.

“I think it would have become incredibly monotonous after the first week or two,” said Phil.

Prisoners were also put to work on tasks ranging from net-making to carpentry, book-binding to shoemaking and dressmaking, as well as washing.

“They did a minimum of 10 hours a day, but it was quite hard graft. The prison made money out of what they could sell,” said Phil, adding the workload was to keep prisoners busy but also help rehabilitate them after release.

The Victorians were quite heavy on rehabilitation, especially with the habit and repute thieves”

“The Victorians were quite heavy on rehabilitation, especially with the habit and repute thieves. In amongst the detail of the work they were doing, there is also comments made about scripture readers being employed. They were obviously looking at the spiritual wellbeing of prisoners. There was also teaching of reading, writing and cyphering, that would have been arithmetic.”

But for all that, Victorian prisons were still forbidding and grim places to end up – as anyone who has visited Peterhead Prison Museum can attest, said Phil.

He said: “I had the dubious privilege of visiting Craiginches Prison just after it closed. These Victorian prisons were hellish places. I can’t imagine being incarcerated in one of them. Apart from the time you were occupied doing the labour and the meagre food that was on offer, you would have had an awful lot of time just to think. That must have been incredibly hard.”

Shedding light on forgotten stories

Phil hopes his event will shed light on untold social history about a forgotten part of society and help people today realise how hard life was for them, especially women.

“The fascination with Victorian criminals and their photos may be the fact you know there’s a snippet of a story there, but there’s an awful lot of detail we don’t known. That was what I was trying to fill in with the blog.”

His webinar is just one of a whole series of Granite Noir events running from February 19 to 21, including talks from leading authors such as Ian Rankin, Val McDermid and Jo Nesbo.

There will also be workshops and online events, all free. For more information go to www.granitenoir.com