It was a battle which went one way, then the other, and summed up the slightly bonkers world of boxing in the 1970s.

The contest featured the little Scot Ken Buchanan, who had become a sporting sensation in his homeland, pitted against the dangerous Ruben Navarro, the “Maravilla Kid”, who gained the support of almost the whole crowd when the event was staged in his native Los Angeles.

Fifty years ago, there were still fractious arguments and rancorous spats between the different governing bodies, the WBA and the WBC, but there was also a shady underside to the whole fistic business which ensured bouts were often organised on a wing and a prayer, a nod and a wink, with organised crime syndicates lurking beneath the surface and pulling the strings.

Yet few had the surreal aspects of this world lightweight tussle between the duo who had been scheduled to fight entirely different rivals until a few days before they met.

In Buchanan’s case, his original opponent, Mando Ramos, pulled out with a groin injury just 72 hours before their meeting on February 12 1971.

Navarro, for his part, had been billed to lock horns with Jimmy Robertson on February 25, but suddenly he was offered a crack at the world’s No 1.

And he grabbed it.

A frantic preparation for the challenger

Navarro was forced to embark on a rigorous training regime to prepare for this challenge. But he responded with an effervescent have-gloves-will-travel attitude.

He spent hours in the gym, jumped in and out of constant hot and cold baths, and worked out for five rounds the day before he tackled the reigning champ. By the end, if he had been asked to run through a brick wall, he would cheerfully have accepted.

There were some pundits who questioned whether the fight should proceed at all, but this was the 70s, the promoters held sway, the respective managers sorted out the purses and it was agreed that Buchanan would receive $60,000 and Navarro $15,000.

The latter realised he was the underdog, but he promised his army of fans that he would have a surprise or two for his opponent.

And, when the action commenced, he quickly showed he was true to his word.

The Scot was caught by surprise at the start

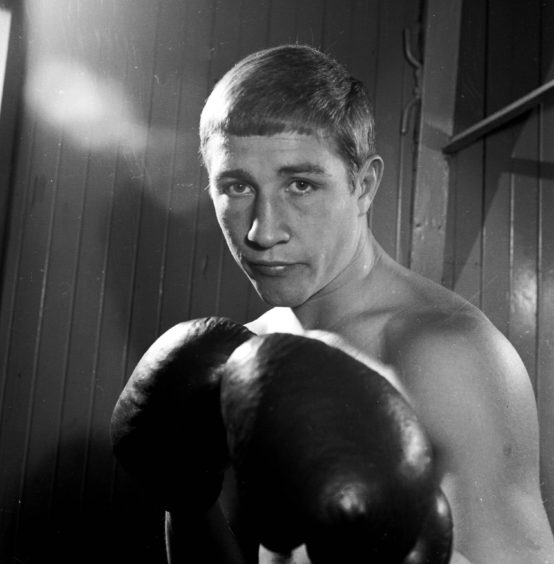

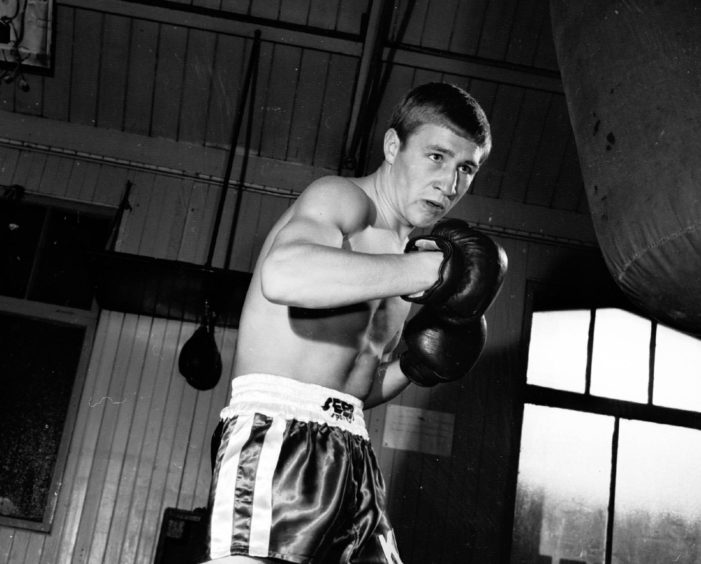

Buchanan had amply demonstrated his skill, stamina and superb technique in becoming king of the world just a few months earlier when he defeated Ismael Laguna.

It was a bruising, lung-bursting tussle, staged in sweltering temperatures which might have impacted on other, lesser characters.

But this redoubtable fellow had a huge heart and, fresh from trading banter and boxing stories with Muhammad Ali, he rose to the occasion and imprinted himself on the sport throughout the globe.

Navarro must have known he couldn’t triumph without knocking out his rival early in the proceedings. So the rush job of arranging the contest was replicated in the ring.

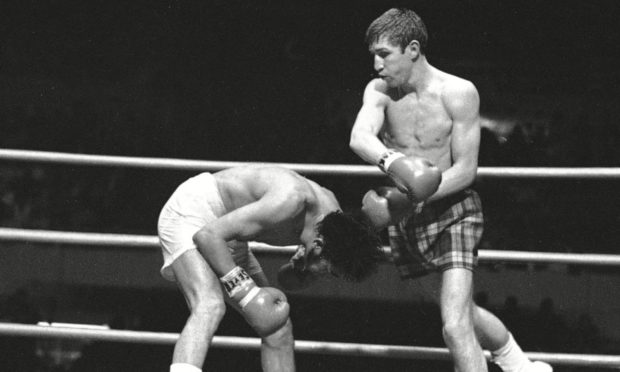

And, even as more than 10,000 spectators cheered on the swashbuckling American, he launched an opening attack that virtually rushed Buchanan off his feet – and lo and behold, he was on the canvas in the very first round.

However, the referee Arthur Mercante ruled it was no knockdown, even as the crowd vented their displeasure.

Yet these early charges from Navarro definitely made an impression on his opponent. For the first three rounds, it was a tumultuous display.

The fight went the distance with only one winner

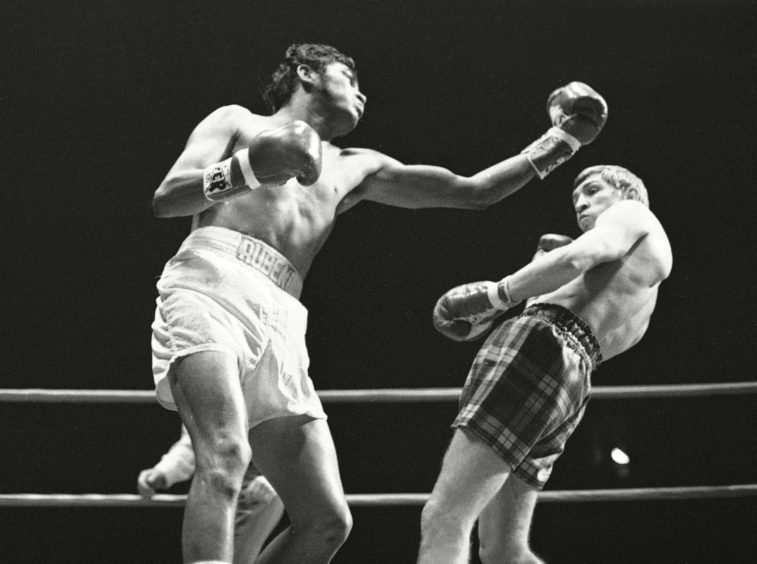

The question was whether Navarro could maintain this electric level for any length of time or whether Buchanan would turn the tide in his favour.

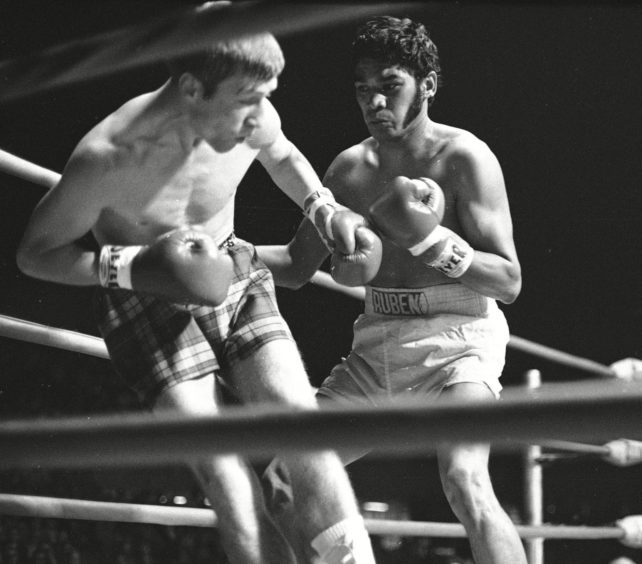

Gradually, inexorably, he wrestled back control, began dominating all the close-quarter exchanges and nagged away at his rival’s resolve like the toothache.

There was nothing wrong with Navarro’s resilience in the face of such a sustained assault. He clung on and refused to be put to bed, even though his performance increasingly turned into a damage limitation exercise.

However, the momentum was flowing in just one direction and, as the Pasadena Star-News reported the following day: “He had been courageous, but midway through the action, Navarro started to tire as if his earlier efforts had all caught up with him and it was then that the dancing and the jabbing Buchanan began to pour it on.”

The referee ruled it 9-4 in the Scot’s favour at the end as did judge Lee Grossman.

Harry Gibbs, the other official, scored it 9-2 to Buchanan. He had achieved his goal and served notice of his quality, oblivious to the faltering scenes in the opening stages.

There were different views on the American’s tactics

Buchanan acknowledged that he had been in a real scrap after cementing his victory, but argued that the tactics employed by his opponent were borderline cheating.

He said: “I was slow and cold at the beginning and I turned my back on his rushes because I wasn’t used to them and they wouldn’t have been allowed in Britain.

“But I soon got warmed up, I got into my rhythm, and I think the people in the crowd appreciated good boxing.

“Fair play to him, though. He came out with a plan, he was going at 100mph, he succeeded for a wee while and he never gave up.”

Navarro, meanwhile, countered: “I thought that I should have had a knockdown in the first round because it was a good punch to the chin.

“He never really hurt me as the rounds went by, but as I told him in the dressing room: ‘You’re a fine fighter, a very good champion and I know of only one man who can beat you – me, when I have had more time to train.”

It was a rematch which never materialised as Buchanan prepared for stiffer tests. Which included trying to master dancing with a member of the Royal Family.

Strictly dumb dancing from Scotland’s world champion

Ken Buchanan was one of the most famous Scots on the planet in the early 1970s. He rubbed shoulders with celebrities, enjoyed talking to people from other pastimes and pursuits and even met the likes of Sean Connery on his travels.

However, while he might have been an agile, sprightly twinkle-toes in the ring, he was no threat to Gene Kelly or Fred Astaire on the dance floor – as he discovered in forthright fashion from a member of the Royal Family.

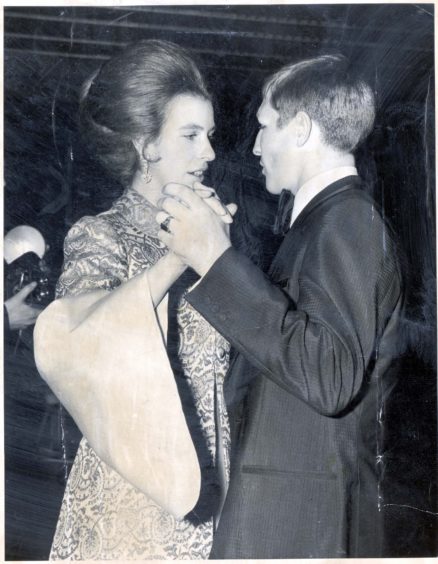

He recalled: “There was also one night in 1971 when I was named the British Sportsman of the Year – Princess Anne collected the women’s award – and the pair of us had to dance together at the dinner.

“Anyhow, I had gone to lessons for three months – my dad was a terrific dancer – and I thought I would be a natural, but I wasn’t.

“In fact, I was more nervous than I had ever been before walking on to the floor. But, like a fool, I told the princess: ‘Don’t worry, hen, dancing is in my blood.’

“Well, after a couple of minutes of shuffling around with not a shred of co-ordination, she spoke to me through clenched teeth: ‘You must have a circulation problem then because it hasn’t reached your feet.’

“That was me stymied – after all, what could I say to royalty?”

Duran eventually took the wind out of Ken’s sails

Buchanan was still only 27 when he travelled to the United States to tackle the formidable Roberto Duran in 1972 – and the ensuing events made it one of the most controversial scraps in boxing history.

It all went down at Madison Square Garden, where Buchanan, pitted against the Panamanian Roberto Duran, nicknamed ‘The Hands Of Stone’, competed so perseveringly and courageously that the South American eventually rammed his knee into the groin of his adversary, leaving him unable to continue amid bedlam.

To many of the throng, it was a blatant transgression, but Buchanan has grown accustomed to dealing with life’s slings and arrows and occasional low blows.

He said later: “It still rankles with me, of course it does. Duran robbed me. He attacked me after the bell, and should have been disqualified.

“I could have gone on, even though the pain was indescribable, but the referee was having none of it. It is something that still lives with me.”