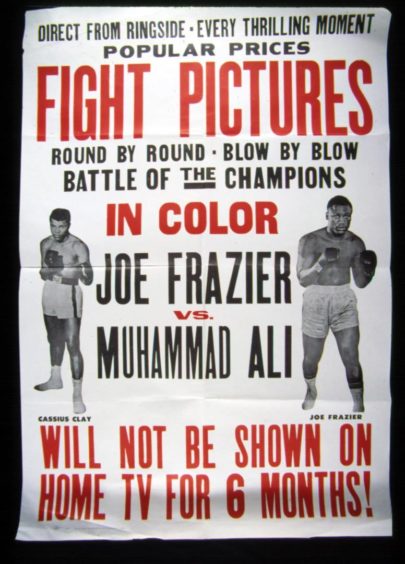

It was one of the most brutal, belligerent battle of wills in the whole history of sport.

And although Muhammad Ali was laughing and joking at the start of the “Fight of the Century” at Madison Square Garden 50 years ago, his opponent, Joe Frazier, famously silenced the man who proclaimed he could float like a butterfly and sting like a bee.

This was in the days when boxing bouts were about far more than jabs and upper cuts.

Ali, the darling of the younger generation and the voice of those against the war in Vietnam, was in his pomp and had started to believe his own hype.

He mocked his rival relentlessly, called him “ugly” and ridiculed his boxing style in the build-up to their meeting in New York on March 8 1971, yet both men had legitimate claims to the title of world heavyweight champion.

An undefeated Ali had won that honour from Sonny Liston in 1964 and successfully defended his belt until he had it stripped by the authorities for refusing to serve with the US Army three years later.

Smokin’ Joe was the real deal in the ring

But Smokin’ Joe had picked up the torch in his absence and collected two championship belts through knockouts of Buster Mathis and Jimmy Ellis.

Although lacking the oratory and charisma of The Greatest, he was a genuinely gifted pugilist with a formidable work ethic and an inner rage at how he had been trashed by his adversary in the weeks prior to their collision.

It turned into one of the most remarkable nights in both of their lives. In addition to the millions of fans who watched the pulsating events on broadcast screens throughout the globe, the Garden was packed with a sell-out crowd of 20,455 who paid $150 (around £1,000 in today’s currency) for the most expensive ringside seats.

Hollywood came calling with a galaxy of stars in the audience, including Norman Mailer, Woody Allen and Burt Lancaster.

When Frank Sinatra discovered that he couldn’t get his hands on any tickets, he did it his way and took photographs for Life magazine.

Even Nelson Mandela, who was incarcerated thousands of miles away in South Africa, spoke about how excited everybody was for the fight.

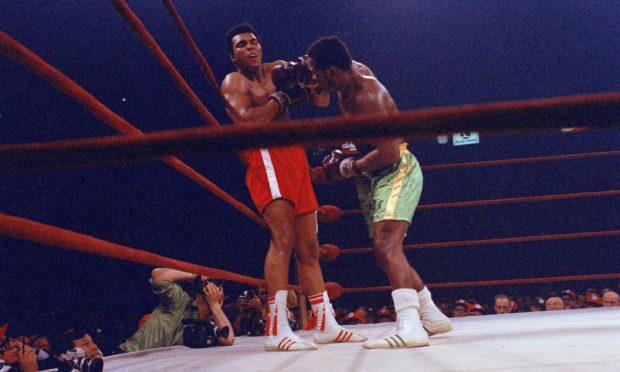

Sometimes, this level of expectations produces an anti-climactic damp squib. But there was none of that as the combatants knocked seven bells out of each other during a ferocious, utterly strength-sapping clash whose ugly beauty captivated the audience.

At the end of the second round, Ali waved a dismissive gesture at Frazier as if to say: “Forget it, punk, I’ve got this under control.” Then, at the climax of the third, he even walked back to his seat with a roguish wink to the press gallery he had courted for the previous decade and longer. It was hubris and, as usual, he seemed in his element.

But, beneath the surface, he was growing increasingly concerned and being tested severely by Frazier who, despite his disadvantage in height and reach, was nagging away at his foe’s resolve with a blitzkrieg of bruising punches to his stomach and gradually, inexorably, inflicting a massive pounding.

Cooke sent a Letter from America about the fight

One of the journalists who watched this epic confrontation was Alistair Cooke, the man whose weekly Letter from America became a radio institution on both sides of the Atlantic for more than 50 years.

Cooke later recalled how Frazier had performed “with the impatience of a squirrel burying nuts” and was in the ascendancy by the sixth and seventh rounds. Could he keep it up? Oh yes, he very much could.

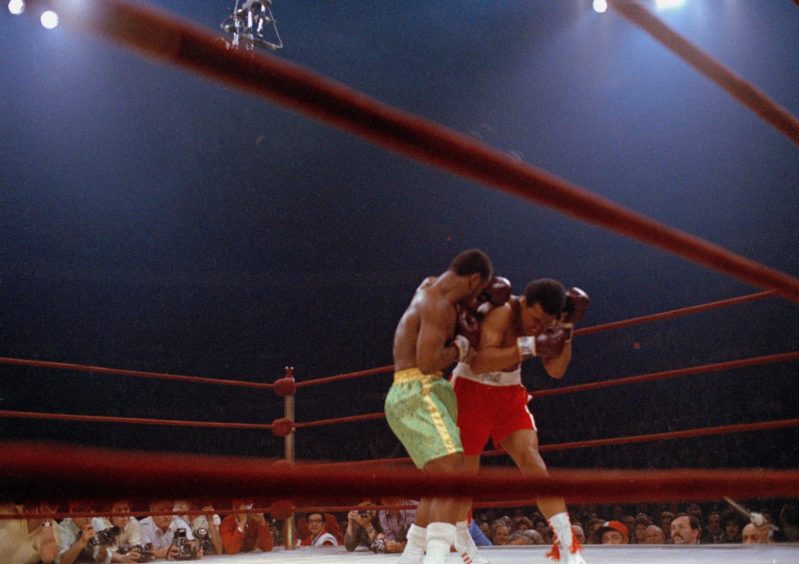

As the veteran broadcaster said: “In the eighth round, all the bogeymen predictions began to come true. Frazier was bunched over Ali’s stomach, his head rammed against the big boy’s chest, and rattling away like a piston in heat.

“By this stage, the crowd roared ‘Joe, Joe, Joe’, but it was in tribute, not a scream of defiance. From then on, all the stuffing, the visceral and the egotistical, had gone out of Ali.

“All he could do was look back constantly into the ropes and writhe at the agony that was seizing his middle. Frazier was slowing down, but he was so much in control that, in one instance, he lifted Ali irritably from the ropes and planted him solidly in the middle of the ring.

‘He staggered around like a hopeless drunk’

“The 11th round was a nightmare which nobody who saw it will ever forget. Ali must be the most unyielding metal since the discovery of iron, but he was pounded in the middle and on the shoulders and his head began to flop like a pendulum. He staggered around like a hopeless drunk – and another 30 seconds would have finished him.”

However, neither of these warriors was prepared to hit the canvas.

In the closing stages, Frazier noticeably tired and was suddenly engulfed by a flurry of long lefts and short jabs from his opponent.

It might have proved his undoing, but he dipped into his reserves and unearthed another vial of vigour.

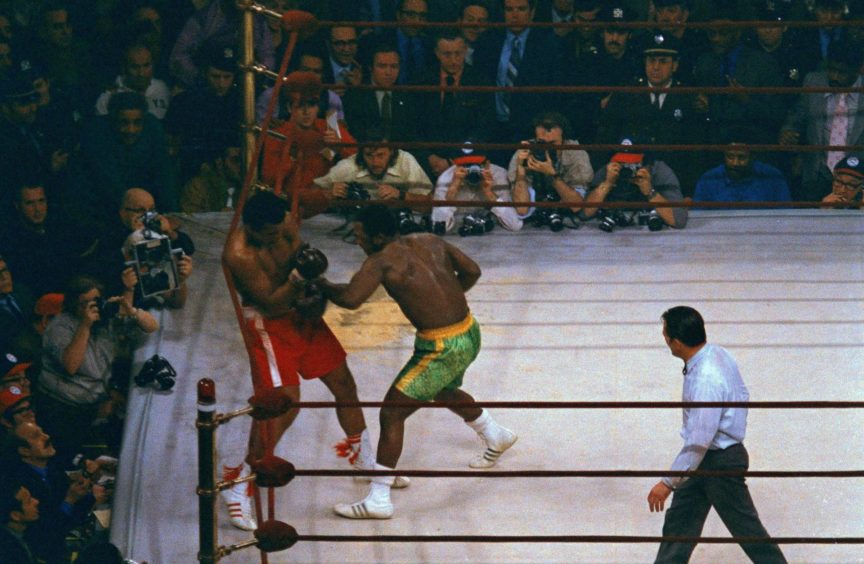

At the end, there was nearly a knockout when Ali was pummelled with a walloping left hook.

His legs buckled and he was down and kneeling, but then almost miraculously rallied anew.

No matter what punishment he had already sustained, he was sending out his affirmation that he was not going to succumb and surrender his record without staying the distance and waiting for the officials to arrive at their verdict.

A unanimous decision and the changing of the guard

There was no doubt about the outcome, however. The judges, to a man, awarded the victory to the underdog Frazier by 9-6, 11-4 and 8-6 with one round tied.

Ali refused to publicly accept the defeat and barely had the dust settled before there was the inevitable talk of a rematch with promoters queuing to broker deals.

But, like most film sequels, they couldn’t live up to the original as Ali triumphed in the Super Fight 11 in 1974 and the Thrilla in Manila the following year.

In the end, his personality changed after his loss and there was an anger and resentment in his demeanour which was evident when he subsequently travelled to Britain to appear on chat shows.

Ali lit the torch at the 1996 Olympics

In the final analysis, his lustre was undimmed for the rest of his life, despite suffering the cruel effects of Parkinson’s Syndrome and there wasn’t a dry eye in the house when he lit the Olympic torch in Atlanta in 1996.

But he had shown that he was as mortal as any other competitor in the ring and Alistair Cooke summed up the consequences perfectly in The Guardian on March 10.

As he wrote: “On the way down to the Garden, I asked my cab driver how he figured the fight. ‘I really don’t know’, he said, ‘but I’d like to see Frazier cool him down a little’.

“That he assuredly did. You could sum the whole thing up in nine short words by Frazier, who said afterwards: ‘Those body punches. One, two, three. They add up.”