A collective pardon for hundreds of Scottish miners questionably convicted and fined for breaches of the peace during the bitter strike in 1984 is well overdue.

I, for one, hope Justice Secretary Humza Yousaf’s consultation on the criteria for such a pardon is concluded swiftly and the stain and injustice is lifted from men who were fighting for their livelihoods and their communities.

For me, the miners’ strike of 1984 wasn’t some distant event. I was on the frontline of it as a young reporter, covering the picket line conflicts at Bilston Glen as it turned from an industrial dispute over proposed pit closures into an ugly ideological war between Arthur Scargill and Margaret Thatcher, each determined to break the other.

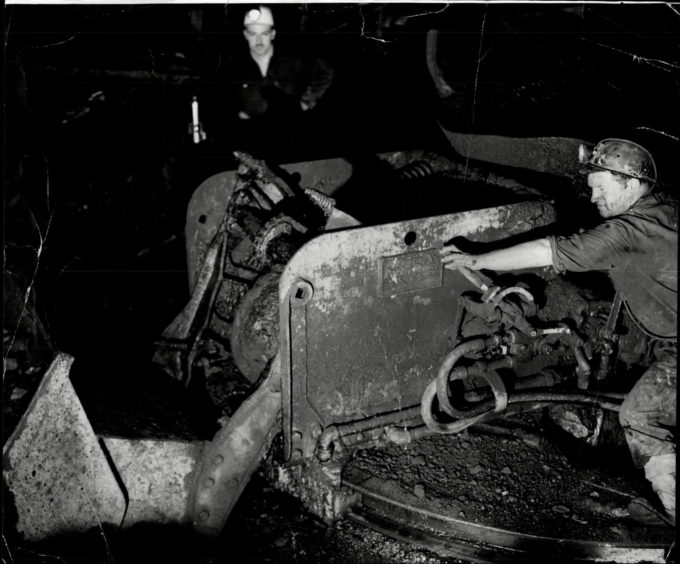

Miners were the pawns and pits were the battlefields, along with other industries like the steelworks at Ravenscraig, in this the age of secondary picketing and flying pickets.

As trouble flared at these flashpoints, I was assigned to cover morning and afternoon shift changes at Bilston Glen, one of Scotland’s biggest and most modern collieries, on the outskirts of Edinburgh.

Walk of shame through the gates

The most daunting aspect at first was the brutally early morning rise to get there on time.

Initially, though, it was an easy enough job. Turn up, chat to some of the pickets, get some quotes from local union leaders, then stand back and watch them shout and chant “scab” at miners who were breaking the strike by making a walk of shame through the gates, while the police kept pickets at a distance.

Phone the story in, then back to the office for a bacon roll and coffee. Repeat in the afternoon.

But then the mood changed and soured. Now, on the evening news, we were watching increasingly violent clashes between pickets and police at places like Ravenscraig. It was worse in Yorkshire, with Orgreave an all-out pitched battle played out in the modern era.

Attitudes hardened, with miners now firm in the belief they were fighting not just for their colleagues’ jobs, but their own, for their industry, for their way of life, for their communities.

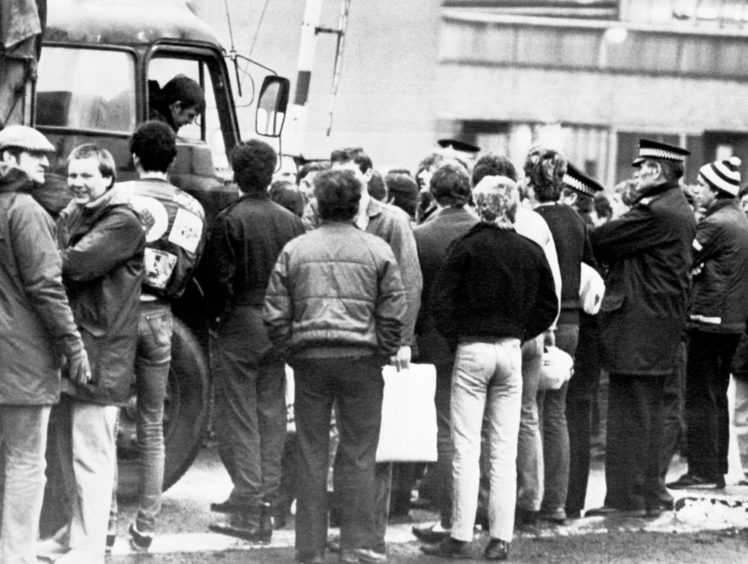

Those friendly chats near the gates of the colliery were gone now. Instead, a line of police stood across the road, keeping an angry line of pickets away from the buses now driving strike-breakers into the mine.

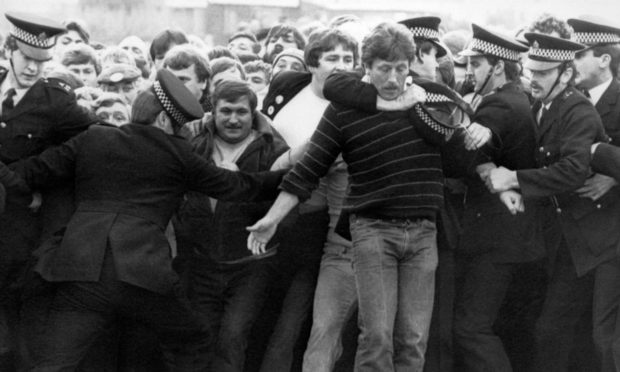

And then the swearing and shouting became a charge, the charge turned into tussling, as the numbers on both sides swelled and a full on fight broke out between the ranked miners and cops. Watching from behind the police lines – we were told not to go on the other side – it was hard at times to make out what was going on.

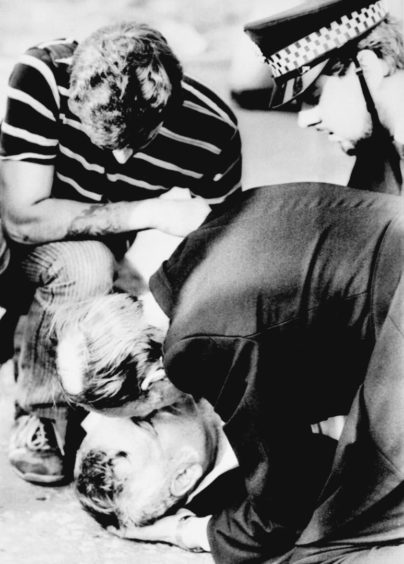

It was a press of shouting, swearing men, fists flying, boots going in, bodies ending up on the grounds, both police and pickets. Every so often, a picket, arm twisted up his back, would be frogmarched into a police van.

Every so often a cop, cut and bruised, would be let away from the front of the affray by concerned colleagues. Exactly the same was played out on the other side of that flailing mass of bodies. People were getting hurt.

It wasn’t this way every shift change. Many were just a case of shouting and yelling at the buses as they went in. Men cursing and swearing at people who before had been their colleagues, neighbours and friends. Turning away in disbelief when they saw someone they knew on the “scab bus”.

Not fists that were thrown but bricks

Often, the police merely had a token presence, as did the miners.

Other times there were almost too many bodies to have an accurate count. On occasions it wasn’t fists that were thrown but planks and bricks taken from nearby gardens and walls. It was ugly and hard to watch.

There were moments of levity, believe it or not. The strike lasted through the summer and the local lemonade factory handed out bottles of juice to police and pickets alike. Although the pickets got plastic ones.

One hot afternoon, the police had just a thin blue line across the street, hours before a shift change as their colleagues lounged on grass banks. Suddenly a mass of pickets came marching up the road, heading straight for them, silent but determined. Cops were pulling on tunics, piling in behind their colleagues to bolster their line when the miners stopped, a couple of feet away. Then they burst into a pointing chant of “spot, spot, spot the loonies, now” laughing and cheering and walked away into the sunshine.

My personal wry smile came on the day there were rumours police were to deploy riot gear at Bilston Glen for the first time in the dispute. These were the heavy helmets, shields, gauntlets and batons we had seen in other places already. Scary stuff.

I was heading for my spot behind the police lines when I noticed a double-decker bus, the lower deck racked with said shields and helmets.

Being a good news hound, I asked the senior police officer in command at what point, he would deploy the riot gear. He said, emphatically, there was no riot gear at Bilston Glen and was irked I would even suggest such a thing. Which was when the double-decker bus pulled up behind him.

“What’s that then,” I asked, pointing at it.

He turned round, glanced in and, without missing a beat, said: “Protective equipment.”

The strike ground on for more than a year. It was hard to watch the desperation growing among the miners and their families. It was gut-wrenching to watch these communities as much at war with each other – as more desperate men returned to work – as they were with authorities.

Cost of defeat would be heavy

Eventually, it became clear they couldn’t win. They had to go back. And they knew the cost of defeat would be heavy. They were right.

Bilston Glen is long gone. There are no deep mines left anywhere in Scotland. None in the whole of the UK.

The mines that fuelled the industrial revolution and built a nation’s prosperity had vanished. The communities which had worked those pits were gone, a way of life consigned to a footnote of history.

But there are still scars left, anger and hurt felt. Much of that stems from the way the strike was policed, court cases handled and sackings inflicted. Many of the men saddled with a criminal record and left without a job had never been in trouble in their lives before or since. Little wonder an independent review in Scotland last year suggested miners be pardoned for certain offences related to the strike, now being pushed forward by the justice secretary.

What happened was wrong 37 years ago and it is wrong now. Time to put it right.