With a nickname like the Granite City, much of Aberdeen’s history can be seen in its architecture, but many of its buildings are at risk.

From opulent underground toilets to much-loved and long-gone shops, 54 of the city’s buildings have seen better days.

Scotland’s Buildings at Risk register seeks to identify buildings across the country which have historic or architectural merit, and are damaged, derelict or facing destruction.

Often sites that meet the criteria are listed or in a conservation area, empty, neglected or have been targeted by vandals.

As well as renowned buildings like the Bon Accord Baths and Broadford Works, the Granite City has many forgotten architectural gems, and we take a closer look at six of them.

Union Terrace Gardens Public Toilets: then and now

Risk: Low

Condition: Fair

When the toilets under the arches at Union Terrace Gardens were first unveiled in the 1890s, the majestic facilities were far better than most Aberdonians enjoyed in their own homes.

But after falling into disrepair and being locked up nearly two decades ago, work has recently begun to restore the once lavish loos to their former glory.

The gardens formally opened on August 11 1879 with a large crowd “including a considerable proportion of children” excitedly waiting for the gates to be unlocked.

But it was 1892 before the Art Nouveau toilets were unveiled in the corner of the gardens underneath the busy Union Terrace above.

Featuring tens of thousands of elegant tiles in varying shades of sage green and cream, stepping down into the B-listed lavatories is a step back in time.

From elegant ceramic ceiling cornicing and mahogany fittings down to the monochrome Greek keystone mosaic flooring – there was no expense spared.

At a cost of £1400 – £182,000 in today’s money – the “admirable” interior enamel work was carried out by Doulton of Lambeth in London.

Aberdonians were charged the princely sum of a penny for “a wash and brush up” or for use of a closet.

The highly-decorative toilets feature an unusual curved wall of 23 urinals set in marble-effect stalls, as well as cubicles with glass-fronted cisterns and coin-operated brass locks.

Men using the grandiose gentleman’s loos from 1914 onwards did so directly underneath the statue of King Edward VII which was installed on the street above.

While the unveiling of additional female toilets in 1916 detailed that “it was done up with claret and tea rose-coloured tiles”.

Flushed with success, the Aberdeen Town Council cleansing committee gave the new loos a quick inspection before enjoying tea at the nearby Grand Hotel to celebrate.

Many Aberdonians will have fond memories of the toilets’ splendour, but their subterranean setting in the shadows attracted vandalism and crime.

For many years, the loos were threatened with closure and they were added to Scotland’s Buildings at Risk register.

In 1996, the late councillor Jill Wisely passionately campaigned to have the toilets refurbished for the convenience of future generations.

She said: “These toilets are amazing, quite unlike any other. I think it would be a terrible miss for Aberdeen if this building is allowed to deteriorate any further.”

But the loos continued to languish until they were closed in 2003, perfectly preserving Aberdeen’s Victorian architecture behind lock and key.

In 2012, a fresh bid to renovate the toilets was panned as the council would have had to spend a lot more than a penny renovating them – receiving a potential quote of £2.5 million for work.

But now, the toilets are being upgraded and restored as a key part of ambitious £25.7m plans to develop Union Terrace Gardens.

A small amount of demolition has recently taken place to bring the toilets back into use to improve access.

The desire to save the loos was highlighted in a city council planning document from 2018.

It stated “the restoration and reuse of the derelict Victorian toilets will remove an important B-listed building from the Buildings at Risk Register”.

Weaver’s Shed, Skene Lane: then and now

Risk: Low

Condition: Poor

Little more than a ruinous bothy, it is easy to dismiss the unassuming rubble building behind Skene Street as a crumbling old garage.

But behind the derelict walls of the Weaver’s Shed on Mackie Place would once have been a hive of activity in the heart of Aberdeen’s historic Denburn Valley.

Thought to date from around 1800, the small stone shed provided a unique glimpse into life and the textile industry in 19th century Aberdeen.

Now silent, the workshop would once have rattled and clattered with the sound of looms for handweaving textiles before the advent of power looms in the Industrial Revolution.

Handweavers were highly-respected master craftsmen who turned yarn into fine cloth for merchants to sell on.

The men and their families often lived and worked in cramped conditions like the Weaver’s Shed, but skilled workers earned a decent wage.

Now an empty monument to a long-gone industry, there have been calls over the years to have the building turned into a folk museum dedicated to a bygone age.

In 1987, the building was re-roofed and made watertight for the sum of £6,000, but plans to turn the Weaver’s Shed into a tourist spot unraveled.

The old workshop has continued to deteriorate and now has bricked up windows, damaged stone work, missing roof tiles and vegetation growing in masonry.

The interior is no longer watertight and is littered with fragments of roof tiles, while the masonry looks damp.

Palmerston Road Smoke Houses: then and now

Risk: Moderate

Condition: Poor

Aberdeen’s fish produce was once so famous that it was a top attraction for “an army of holidaymakers” seeking to take home some edible fare.

A report in July 1929 added that “the fame of Aberdeen ‘smokies’ and kippers has spread throughout the country, to the benefit of local fishmongers”.

Aberdeen lead the way in the white fish trade, and during the Victoria era the skyline was dotted with brick kilns.

But now, only a cluster of traditional smoke houses remain on Palmerston Road, eclipsed by the modern expanse of Union Square Shopping Centre.

The Poynernook Road area, by the Albert Basin harbour, has long been associated with fish landings and processing, and traditional smoking continued on the site into the 1990s.

Fresh from the North Sea, catches would be expertly prepared and strung up wet inside the protruding roof ridges of the brick towers, designed for ventilation during the smoking process.

To cold smoke haddock, a small wood fire would then be lit below, and using sawdust to smother the flames, workers smoked the racks of fish overnight.

The vents on top of the buildings would be manually opened to aid the smoking method, with some of the old trapdoors still visible on the kiln on Russell Road.

But by the Millenium, kiln smoking was all but gone and the old buildings have since fallen into disrepair.

The three category C-listed smoke houses were added to the Buildings at Risk register in 2019 and are deemed to be in a poor condition.

The ventilation doors which would once have billowed with smoke are boarded up and rotting, while blocked-up doorways are covered in graffiti.

But just across the river in Torry, the tradition of fish smoking is still being kept alive in by master curers John Ross Jnr.

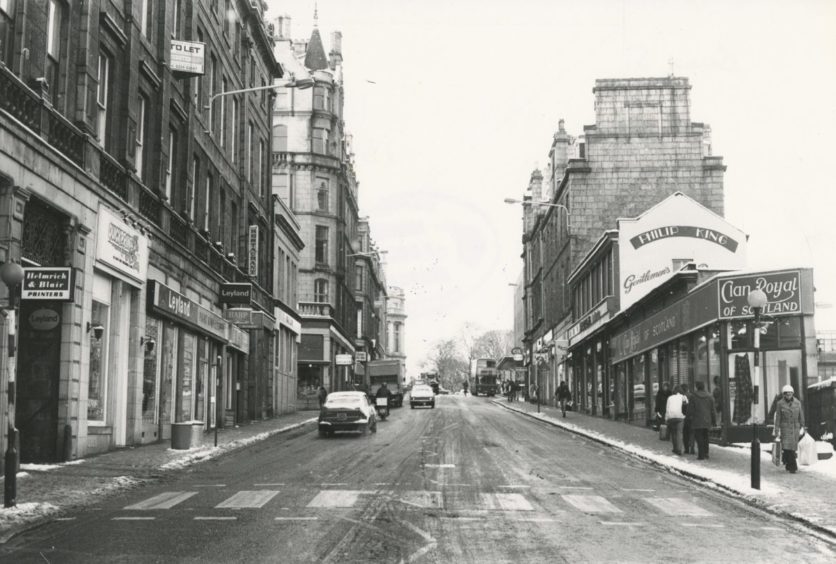

Victoria Buildings, 32-52 Bridge Street: then and now

Risk: Low

Condition: Fair

When the Victoria Buildings were unveiled in 1881, just a stone’s throw from Aberdeen Railway Station, the magnificent structure was designed to dazzle.

With its epic proportions and intricate decorative details, the building would have been one of the first Victorian travellers laid eyes upon when strolling up Guild Street from the station.

Designed to be admired from afar, these days hundreds of people pass by daily without so much as a glance up at its classical carvings.

Where the ground floor was once filled with bustling businesses, it’s now largely empty making it easy to overlook in passing.

The huge granite structure – one of Aberdeen’s biggest pre-1960 builds – was designed by Aberdeen architects Alexander Ellis and Robert G. Wilson.

Remarkably it was built into a slope to fill the whole void between Crown Terrace above and Bridge Street below, to the right of the granite steps linking the two levels.

According to the Buildings at Risk register, it was an unusual build: “Its scale and style is more reminiscent of a city chambers or other municipal building.”

Built as commercial premises, the facade features a curious mix of Classical style and Egyptian motifs, reflecting the Victorians’ fascination with Ancient Egypt.

Stretching to 15 window bays wide and five storeys high at its tallest point, the imposing structure was a show of Aberdeen’s wealth.

And with decorative pillars topped with carved papyrus palm detailing and rooftop balustrades, the building wouldn’t be out of place on a grand estate.

The architects who built it moved into an office at 34 Victoria Buildings in 1882, while tailor John Mitchell set up a shop at 42, and Thomson & Thain, purveyors of gloves and cashmere, opened a store at number 52.

Picture framer John Alderson took over number 42 in 1893, while the Belgrave at number 32 was the place to go for tea and “first-class” confectionary.

And one proprieter, Mr Mackay of the Sportsman’s Depot at number 50, even claimed to have a magic midge deterrent in an advert from 1901.

Nowadays the canopies of bygone businesses are nothing but a memory, some of the shops units sit boarded up and empty, while others are occupied by adult shops and takeaways.

The Crown Terrace floors which had been used by Prime Cuts steak restaurant have lain empty since it closed during the first oil downturn.

But despite the smashed windows of upper storeys and vegetation sprouting from stonework, the building retains its charms.

363 Union Street (Bruce Millers): then and now

Risk: Moderate

Condition: Poor

Most Aberdonians will better remember 363 Union Street as Bruce Millers, the much-loved music emporium with its famous drum clock outside.

Although Bruce Millers was probably its most well-known occupant – having moved from George Street in 1984 – the shop’s history stretches back to the Georgian era.

Built as a house around 1820, the granite two-storey structure was home to Hampton’s Picture Gallery, owned by Thomas W Hampton, a carver and gilder.

In Victorian times, craftsman Mr Hampton specialised in cleaning, reviving and re-lining oil paintings, as well as re-gilding old frames.

Hamptons made the headlines for exhibiting the largest painting of Dunottar Castle ever seen in Aberdeen.

In the early 1900s, Galloway and Sykes furnishers – selling furniture, carpets and linoleums – bought the premises and converted it into a shop.

The family firm remained at the site until February 1984 and John H Galloway, grandson of the founder, spoke fondly of the company’s time on Union Street.

He said: “That was when it was a village street. We bought a house there and that was one of the first to be converted into a shop.”

The business moved to Justice Mill Lane premises where new showrooms were built.

Later that year, Bruce Millers moved to the bigger Union Street store with room for more instruments, hi-fi equipment and a restaurant upstairs.

Generations of Aberdonians will have memories of happy hours spent perusing the latest chart-topping albums, picking up sheet music for lessons and trying out instruments in the basement.

The shop also hosted a number of bands and artists over the years where fans could meet their musical heroes.

The sadness was palpable when the Union Street stalwart shut up for the final time in 2011 after 111 years of trading.

The building was added to the ‘at risk’ register in 2019 although demolition work had already been carried out with a view to future development.

An external inspection found it vacant apart from a restaurant in the basement, and said “the front elevation is in fair condition, however, the rear wall has been demolished and is now boarded up”.

Plans in 2018 indicated a desire to restore a more traditional shopfront with a guarantee the iconic drum clock would be saved, but any transformation of the Union Street frontage is yet to happen.

The void behind, however, became a temporary extension of nearby Soul Bar last year called the Draft Project.

Provost Young’s House, 28-32 Marischal Street: then and now

Risk: Low

Condition: Poor

Once home to a lord provost of Aberdeen, 28-32 Marischal Street is a townhouse of great historical importance to the Granite City’s built heritage.

Dating back to the 1790s, the three-storey house was built by architect William Dauney and is a prime example of the city’s early Classic architecture.

Mr Dauney, whose nephew was famous city architect Archibald Simpson, built many of the handsome properties on Marischal Street, Aberdeen’s only complete Georgian Street.

The B-listed property was established on the site of Earl Marischal’s lodging, which was knocked down in 1789 to build Marischal Street.

The new thoroughfare, the first in the city to be paved with granite setts, was built on a steep incline and gave direct access to the harbour from the Castlegate.

Provost Young’s House is highlighted as significant of Classical Aberdeen, with circular fanlights above doors and interiors of fine panelling and plasterwork.

The dwelling took on more commercial uses as the decades wore on.

In the late 1890s, it was a tailor and clothiers, and a century later it was occupied by The Aberdeen Photographic Service.

In recent years, the ground-floor units have been in use as Serendipity Hypnotherapy, but concerns for empty upper floors saw the building added to the at risk register in 2019.

Its faded glory is still apparent despite broken windows, fledging pigeons and rotten timberwork.

Have we missed any more hidden gems of Aberdeen’s architecture? Email us at: nostalgia@dctmedia.co.uk