Bonnie Dunbar was inspired to reach for the stars by her Scots grandparents and went on to become a five-time space hero.

Only a handful of other American astronauts have heard the countdown to lift-off from the inside of a spacecraft more often than she has.

Dr Dunbar, 72, worked for 27 years at NASA, successfully completing five Shuttle missions, logging 1,208 hours of space flight and nearly 800 orbits of the Earth.

She also forged links between the RRS Discovery and the Space Shuttle Discovery and was heavily involved in founding the Scottish Space School.

Dr Dunbar’s grandfather left Dundee in 1909

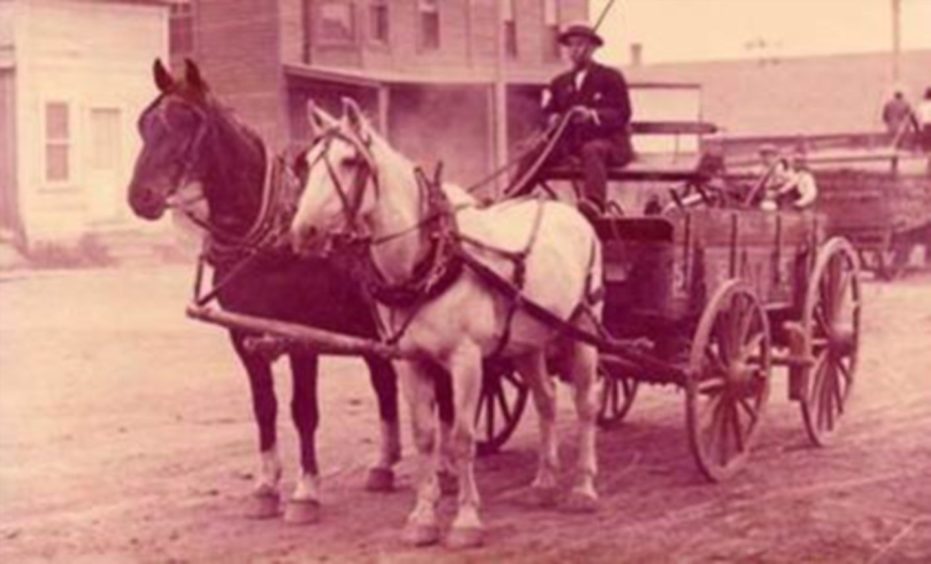

Dr Dunbar’s pioneering grandfather left Dundee for Ellis Island, New York, with little more than high hopes, a pioneering spirit and a bag of books.

He was 19 and had been working in jute factories in Dundee and came with enough money in his pocket to make a new life for himself.

Charles Cuthill Dunbar worked in upstate New York near Syracuse for a year breaking horses and earned enough money to come west.

He established a ranch in a Scottish community in the Condon area of Oregon and met his wife Mary West at a Portland baseball game.

She was originally from near Gardenstown in Banffshire.

“They were married and had three sons of which my father was the middle son,” said Dr Dunbar.

“When grandpa played the fiddle, grandma used to dance the Scottish Fling.

“Unfortunately, I never met her; she died before I was born.

“I learned from him that if you have a vision, and if you follow your dreams, and you’re willing to work for them, this is important.

“You can’t blame anyone else for your failures.

“My grandfather would never take charity.

“He was accountable for his own success or failure.”

Dr Dunbar was raised on a cattle ranch in the eastern Washington town of Outlook and searched for Sputnik in the night sky when she was eight.

“One of those early shows that I used to come home from school and watch was Flash Gordon, and Flash Gordon was exploring the universe,” she said.

“There was no special effects.

“If you look at these programmes today, I think you can even see the wires holding the little spaceships as they fly through space.

“But then actually when I was eight, Sputnik was launched, and I remember that my parents took me out and we looked for Sputnik.

“I’m pretty sure we saw it, because eastern Washington has clear night skies, especially in that time of year, October.

“The Milky Way, when I was growing up, was a band of white across the night sky.

“I mean, you knew that was the Milky Way.

“And I just became completely engrossed in space and stars and HG Wells and Jules Verne, and any book about space I found in our very small rural school, I read.

“So it was kind of natural for me.

“It was what sparked my interest.

“It was exciting, and the questions were unbounded.

“What was out there? What did these places look like?”

Bragging rights in the Cold War Space Race

She was 12 when Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to journey into outer space in his Vostok 1 capsule on April 12 1961.

It was the culmination of a battle between superpowers and gave the former Soviet Union bragging rights in the Cold War space race with the USA.

A world far from Outlook began to take hold.

She said: “When I told my parents I wanted to be an astronaut they were very supportive.

“They were homesteaders and there were people who told them that homesteading was a very rough way of life and tried to discourage them.

“You have to do what you believe in your heart.

“If people didn’t do that there would never be exploration.”

Dr Dunbar applied to NASA for the first time right out of high school.

She received a polite response explaining the necessary credentials.

High on the list was a college degree.

Not mentioned was the fact that NASA was strictly a boys’ club until the late 1970s.

Dr Dunbar enrolled in the University of Washington in 1967 and became the first from her family to go to college.

“My grandfather wished he could have had a higher education,” she said.

“I don’t think he had the chance.

“My parents did not have the opportunity either because they grew up in a very rural area and did not have the money to go to university.

“But they very much wanted me to have that opportunity and although I grew up on a cattle ranch, we worked very hard for it.”

Starting out on the journey to the stars

She gained bachelor of science and master of science degrees in ceramic engineering from the University of Washington in 1971 and 1975 respectively.

Following graduation in 1971, Dr Dunbar worked for Boeing Computer Services for two years as a systems analyst.

From 1973 to 1975, she conducted research for her masters thesis.

In 1975, she was invited to participate in research at Harwell Laboratories in Oxford as a visiting scientist.

She then accepted a position with Rockwell International Space Division in California, where she was Engineer of the Year in 1978.

Dr Dunbar applied when she heard that NASA had opened the astronaut programme to women.

She was one of the 60 chosen as finalists.

However, she was not one of the 35 who made the final cut.

The next time she applied, in 1980, her dream came true when she was accepted as an astronaut candidate.

“I actually applied to become an astronaut, got on to the final list, but wasn’t selected,” she said.

“Instead they offered me a job in mission control.

“So I worked there for two years.

“Then I was selected for astronaut training in 1980.”

Triumph and tragedy on Challenger and Columbia

Her first flight aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1985 broke new ground.

It was the first mission to carry eight crew members, the largest to fly in space.

It launched from the Kennedy Space Center for the West German Spacelab mission.

The mission lasted seven days, 44 minutes and 51 seconds, travelling 2.5 million miles in 111 orbits of the Earth.

Dr Dunbar’s grandfather died just a few years before her first mission.

She said: “I was selected by Nasa when I was 30, and flew in space when I was 35.

“He only missed that by a few years.

“I think he would have been very proud.

“My grandmother would have been thrilled, too.”

About two and a half months later, 73 seconds after the launch of what would have been its tenth mission, Challenger broke apart and disintegrated.

All seven astronauts on board died.

The shuttle fleet was grounded for three years while the accident was investigated.

Dr Dunbar was part of the review team.

She returned to space on a 10-day Challenger shuttle mission in 1990.

Using the shuttle’s robot arm, which she helped to design, she retrieved a satellite that helps to study the effects of space environment on materials.

In 1992 she was back aboard Columbia as payload commander for a 13-day mission which travelled 5.7 million miles in 221 orbits of the Earth.

She wrote her name into the history books again on Atlantis in 1995 as part of first space shuttle mission to dock with the Russian space station Mir and involve an exchange of crews.

The previous year she spent several months in Star City, Russia, training as back-up crew for Mir.

And on Endeavour in 1998 she and the shuttle crew transferred more than 9,000 pounds of scientific equipment, logistical hardware and water from the shuttle to Mir.

Next chapter in the life of Dr Bonnie Dunbar

She stayed on at NASA for another seven years, working in senior management in a number of different positions.

On February 1 2003, Columbia – the spacecraft she had helped build and had flown on twice – broke up during re-entry.

All seven crew members died, including Michael P Anderson, who was a friend and former crewmate of Dr Dunbar’s.

The two had flown together on her last mission.

Dr Dunbar has visited Dundee several times and the city forged close links with NASA when the city’s sea-bound Discovery was twinned with the Discovery Space Shuttle.

She was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Dundee in 2002.

Dr Dunbar retired from NASA in 2005 as associate director for technology, integration, and risk management.

She served as president and CEO of The Museum of Flight in Seattle until April 2010.

From 2013 to 2015, Dr Dunbar led the University of Houston’s STEM Center and was a faculty member in the Cullen College of Engineering.

She became a professor of aerospace engineering at Texas A&M University in 2016.