It was a pitched battle which was done and dusted in less time than half a football match.

By the climax, thousands of men lay dead or wounded, while others were scattered to the wind, pursued by vengeful forces who hunted down their enemies and either slaughtered them or transported them to the West Indies.

Even now, 275 years later, Culloden is a word which provokes strong emotions among the descendants of those who perished on a brooding, boggy moor, east of Inverness in the Scottish Highlands.

Charles Edward Stuart, whose forces were vanquished, is still painted as a romantic figure in some quarters, whose pursuit of the Jacobite cause brought him into direct conflict with the British government.

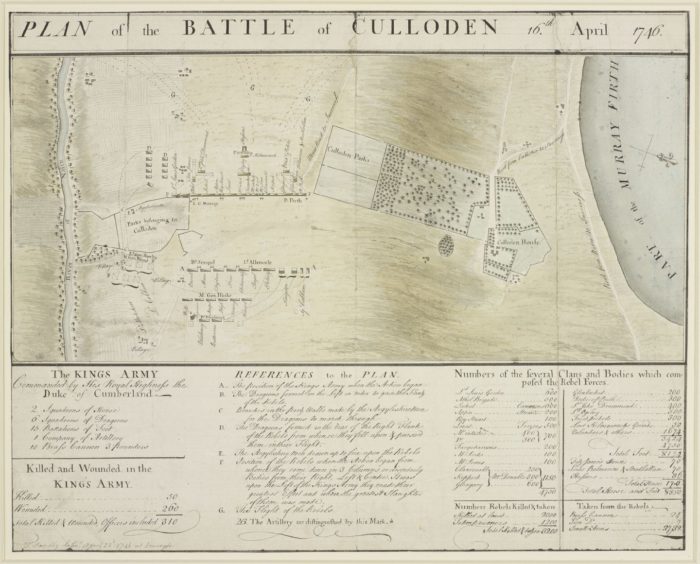

Whereas, his chief opponent, Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, is now almost universally associated with the word “Butcher”, following his soldiers’ scorched earth policy and merciless treatment of anybody who stood against him, during and after the bloody events on April 16 1746.

It was the last battle fought on British soil – yet many of the reverberations and divisions which sparked the hostilities remain relevant today.

Early wins were overtaken by a rout

The Jacobite risings had proved a constant thorn in the flesh of the UK establishment throughout the first half of the 18th century.

But despite the revolts being quashed in 1715, 1719 and 1745, there were still plenty of supporters of the deposed King James II and VII, which ensured that his grandson – most commonly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie – became a popular figure in Scotland when he sailed from France in an attempt to reclaim the throne for the Stuarts, who had been cast into exile.

At first, the young man seemed to possess the swashbuckling qualities and charisma to inspire his troops to famous victories at the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745 and the Battle of Falkirk Bridge the following January.

But these exploits were the prelude to a decisive confrontation between those who supported the Jacobites and those who regarded them as rebels, rogues and renegades. It sparked 40 minutes of carnage and internecine bloodshed.

And the prince fled the scene and spent the next year in hiding before returning to France in September 1747 – even as the recriminations and reprisals continued to inflict a heavy toll on those he left behind.

Reports bear testimony to the cull at Culloden

Bonnie Prince Charlie had assembled an impressive fighting force since arriving in Scotland and had access to many men of immense experience.

However, history has not been kind to his preparations for the clash at Culloden, where he was tactically outmanoeuvred and out-flanked by the Government forces, who held the advantage in every department from numerical supremacy to superior quality of weaponry.

One of the Jacobite survivors, Donald Mackay, summed up the horror of the situation in which he and his comrades found themselves when he later wrote: “The battle began and the pellets came at us like hailstones.

“The big guns were thundering and causing frightful break up among us, but we ran forward and – oh dear! oh dear! – what cutting and slicing there was….

“The English were numerous and we were few and a large number of our friends fell all around us. The dead lay on all sides and the cries of pain of the wounded rang in our ears.”

The numbers didn’t stack up for the Jacobites

Charles, the Young Pretender, who had been born and brought up in the lap of luxury in Italy, possessed virtually no military experience before his involvement in the Jacobite campaign.

However, his army’s early successes convinced him that the so-called ‘Highland charge’, with broadsword in hand, was an irresistible strategy.

He quickly found himself at loggerheads with the best of his commanders, Lord George Murray, who argued against a reliance on this tactic, especially in a setting such as a moor, but whose warnings were signally ignored.

The Jacobites mustered only 5,000 men at Culloden; as many as 2,000 were on operations elsewhere and this was from a total clan fighting force estimated at around 30,000 men. Nor did it help that most of the troops were exhausted by April 1746. They had danced to the Prince’s tune all the way to Derby. But their exertions had gradually, inexorably taken their toll.

In comparison, the Duke of Cumberland was an enthusiastic soldier from a young age and had earned the moniker of ‘martial boy’ as a teenager.

A strict disciplinarian, he restored the confidence of the army defeated at Falkirk, introducing a new bayonet drill to combat Jacobite use of sword and targe (a small shield). His 9,000-strong force constituted a well-balanced force of horse and foot, which was amply supported by cannon and mortars.

Given these disparities, it was scarcely surprising that Culloden swiftly developed into a catastrophe for the Jacobite ranks.

A historian’s hard look at the Culloden debacle

Professor James Hunter, of the University of the Highlands and Islands, has investigated the build-up to the battle and highlighted the increasing divisions and difficulties which bedevilled the Jacobites.

Their earlier optimism and positivity had dissipated after they returned to the north-east of Scotland in the midst of a dreadful winter.

Mr Hunter said: “The ‘cold, stormy weather’ which features constantly in such correspondence as survives from February 1746 impeded Jacobite as well as Hanoverian mobility.

“Writing of that month’s march to Inverness, John Daniel, one of the few recruits Prince Charles had gained in England, observed: ‘When we marched out of Aberdeen, it blew, snowed, hailed and froze to such a degree that few pictures ever represented winter better than many of us did that day. The men were covered with icicles hanging at their eyebrows and beards; and an entire coldness seized all their limbs. It may be wondered how so many could bear up against the storm, with a severe contrary wind, driving snow and hail bitterly cutting down upon our faces, in such a manner that it was impossible to see ten yards before us.

“‘And very easy it now was to lose our companions; the road being bad and the paths being immediately filled up with drifted snow’.”

Culloden’s failings as a choice of battle site

Prof Hunter has little doubt that the seeds of defeat were sown from the very moment the prince decided that Culloden was the right place to fight.

He said: “Expecting the duke’s advance to be resumed next day and determined to retain possession of the town that had long been, and remains, the Highland capital, Charles Edward, on the morning of April 15, got his army into battle-order on Culloden Moor, a flat and featureless expanse of bog and heather on the summit of the ridge separating Inverness and the Moray Firth coastline from the shallow valley of the River Nairn.

“Culloden Moor, 500 feet above sea level and with falling ground on three of its four sides, commands impressive views of Ben Wyvis and other mountains to the north and the hills beyond Strathnairn to the south.

“However, as a piece of terrain on which to do battle, Culloden has little to commend it. Lord George Murray, who would ideally have preferred to draw Cumberland deeper into the Highlands where his formations could be harried at will, was strongly of the opinion that if King George’s son had to be confronted at all, he should definitely not be confronted on Culloden Moor.

“‘I did not like the ground,’ Lord George commented of Culloden. ‘It was certainly not proper for Highlanders’. But Murray’s views were disregarded by Prince Charles Edward, who was now looking elsewhere for advice.”

It didn’t help him or his weary troops. On the contrary, after rebuffing Lord George’s last-minute pleas to move the Jacobite army across the River Nairn, where there was at least some prospect of it being able to launch one of the downhill charges that had long been a favoured Highland battle tactic, Prince Charles determinedly lined up his regiments on Culloden Moor and waited for the Duke of Cumberland to come to him.

The outcome was the destruction of a whole way of life.

The slaughter was fast, furious and sustained

The Scots Magazine’s April edition in 1746 emphasised the sheer scale of the losses which the Jacobites suffered.

It reported: “The battle was very bloody, no quarter having been given on either side while it lasted, which was about half an hour [closer to 40 minutes]. 1,000 of the rebels were left dead in the field; and about 200 were killed or wounded on the King’s side.”

It has now emerged that between 1,500 and 2,000 Jacobites were slain and those who ran towards the hills were hunted down and slaughtered.

The Duke had made his message clear: he wanted this to be the last time the Jacobites posed a threat to the British state. And, as the barbarism continued, he duly achieved his aim, but not without his name going down in infamy.

Even as his troops were left in disarray under heavy fire, Charles fled the field and escaped while his loyal soldiers struggled to protect his flight.

Despite the Jacobites being pursued and persecuted on the Duke of Cumberland’s orders in the aftermath of the calamitous loss, the Prince enjoyed significant help and support in his efforts to evade the UK authorities.

Flora MacDonald was famously visiting Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides when he and a small group of aides took refuge there in June 1746.

One of his companions, Captain Conn O’Neill from County Antrim, was distantly related to Flora and asked for her assistance.

After initial and understandable misgivings, she ensured safe passage to the mainland for herself, a boat’s crew of six men and two personal servants, including Charles who was disguised (unconvincingly) as an Irish maid by the name of Betty Burke. On June 27, the party landed near Sir Alexander MacDonald’s house at Monkstadt on Skye.

It was an incident which inspired one of Scotland’s most famous songs, and eventually, Charles managed to avoid retribution and return to France.

He was able to spend the rest of his life in affluence before dying in Rome 42 years later at the age of 67. Those who fought for him were not so fortunate.

Indeed, the Disarming Act of 1746 forbade Highlanders from carrying weapons and chieftains could no longer execute the law within their domain. The estates of 40 Jacobite leaders were confiscated by the Crown.

To all intents, the battle’s outcome destroyed the old clan structure.

The last word from a professor of the conflict

In the aftermath of Culloden, Lord George Murray wrote an embittered letter to the man for whom he had done so much in previous years.

‘It was surely wrong’, he told Prince Charles, ‘to set up the royal standard [at Glenfinnan] without having positive assurance from His Most Christian Majesty [Louis XV of France] that he would assist you with all his might.’

As Prof Hunter said: “Pro-Jacobite writers have ever since regarded those sentiments as amounting to little better than treachery; that most romantic of twentieth-century Jacobite romantics, Compton MacKenzie, going so far as to call Lord George’s letter ‘contemptible’.

“But Murray, who had more than earned the right to be critical of Charles Edward Stuart, was arguably not too far wide of the mark. It had long been recognised that no Jacobite uprising was likely to succeed in mid-eighteenth-century Britain unless it had active and energetic backing from France.

“By constantly telling his followers that such backing would be forthcoming when he had not the slightest basis for supposing that it would, Charles Edward had been guilty of wishful thinking at best – of bad faith at worst.

“This accusation lay at the heart of Murray’s letter. It is an accusation that has deservedly sullied Charles Edward Stuart’s reputation ever since.”