The British Home Championship of 1981 was fraught with high tension and played against a backdrop of political and civil unrest.

There was a sinister undertone in the build up to the annual round robin competition between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as simmering pressure in The Troubles was reaching boiling point.

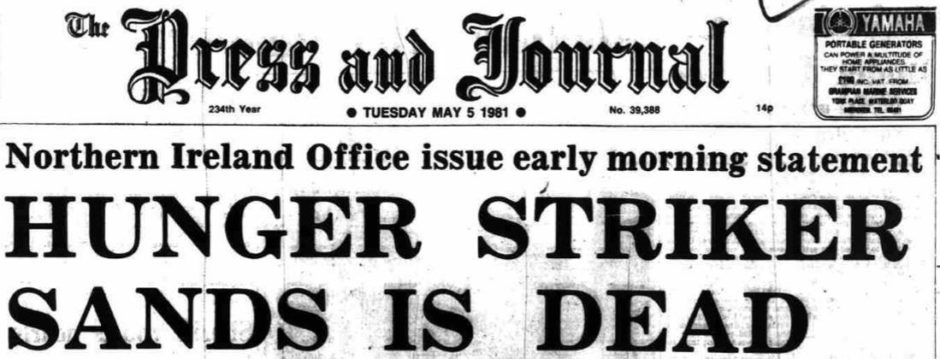

On May 5, just 10 days before the four nations internationals kicked off, conflict between nationalists and unionists in Northern Ireland came to a catastrophic climax.

Bobby Sands, a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and newly elected MP, died in Maze Prison near Belfast after 66 days on a hunger strike.

Sands was number 2,308 on the list of dead during The Troubles.

In the weeks that followed, Northern Ireland were due to play England and Wales at home in Belfast.

But riots were flaring, there was gunfire on the streets, vehicles were set alight, hundreds more British troops were deployed and there was widespread condemnation of the British government.

The last place an English football team wanted to be was the hostile epicentre of anti-government conflict in Belfast.

The England and Wales teams refused to travel for their away ties against Northern Ireland.

The tournament went ahead, what would happen to the unclaimed points was undecided, but Scotland would be the only team to play their three games.

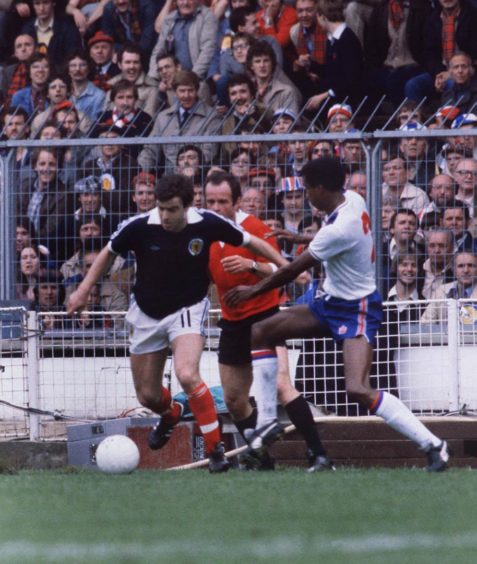

On May 16, Scotland lost 2-0 to Wales in Swansea, but had a convincing 2-0 home win against Northern Ireland at Hampden on May 19.

England and Wales had a goalless draw the following day, before the English side faced Scotland on May 23.

Against the odds

The Scottish fans defied the odds to back their team to victory at Wembley.

The Tartan Army had form for hooliganism, and while light-hearted japes and merriment were tolerated, previous games had descended into chaos at the hands of fans.

In 1977, Scotland won 2-1 against England in the Home Championship – a game that won them the title and famously sent 65,000 fans into a frenzy.

The Tartan Army leapt from the stands and stormed the pitch at Wembley, crushed the crossbar and tore up the turf to take home as a souvenir, in a now iconic moment for Scottish football.

Two years later, thuggish behaviour before and after the team’s fixture with England resulted in the vandalism of tube stations and terracing at Wembley, and 349 Scotland fans were arrested.

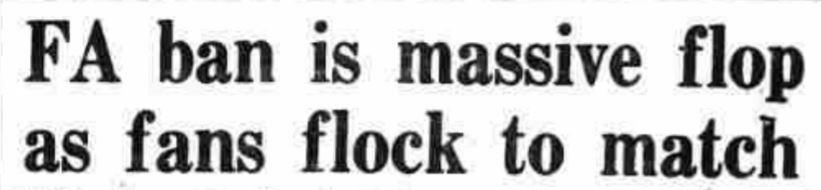

Concerns history would repeat itself, and that London would be under siege once again in 1981, saw English Football Association secretary Ted Croker put a ban on sales of tickets in Scotland ahead of the match in May.

But the Tartan Army weren’t defeated, tickets did a roaring trade on the black market and a 40,000-strong contingent made the pilgrimage south despite railway strikes.

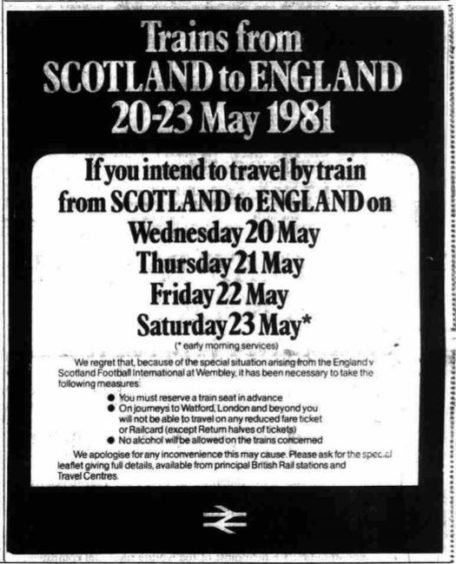

British Transport Police officers had annual leave cancelled and were posted on every football train from north of the border to prevent any hijinks.

Fans travelling from Aberdeen were well warned, with adverts appearing in the Press and Journal warning of a booze ban on trains, to be enforced by patrolling officers.

When the dry trains made it to Central London, fans then faced a 10-mile walk to the stadium after Transport for London bowed to pressure from unions to suspend bus and tube services to Wembley for the day.

Alcohol had already been banned at the ground, but fearing the effects of another Wembley weekend, nearby pubs were shut.

Scotland delivered

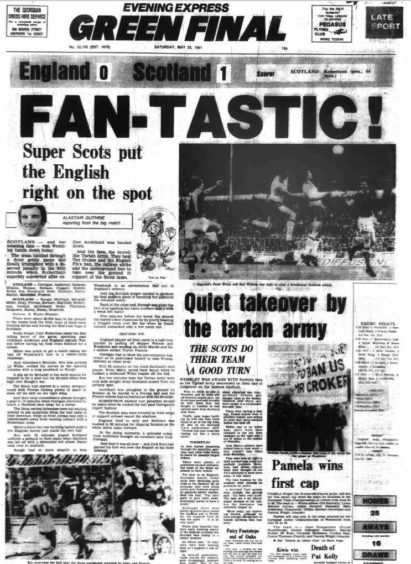

“Ticket ban or no ticket ban, there were lions rampant to the left, lions rampant to the right and a sea of tartan in the middle of Wembley”, reported The Evening Express’ Green Final.

It was a hot early summer’s day, Adam & The Ants were at number one in the charts with Stand and Deliver, and Scotland certainly delivered.

The tenacious Tartan Army were rewarded for their resilience when Scotland emerged victorious.

The match report said “the team battled through a dour, gritty game and finally triumphed with a deserved penalty in the 64th minute when Robertson superbly converted after ex-Don Archibald was hauled down”.

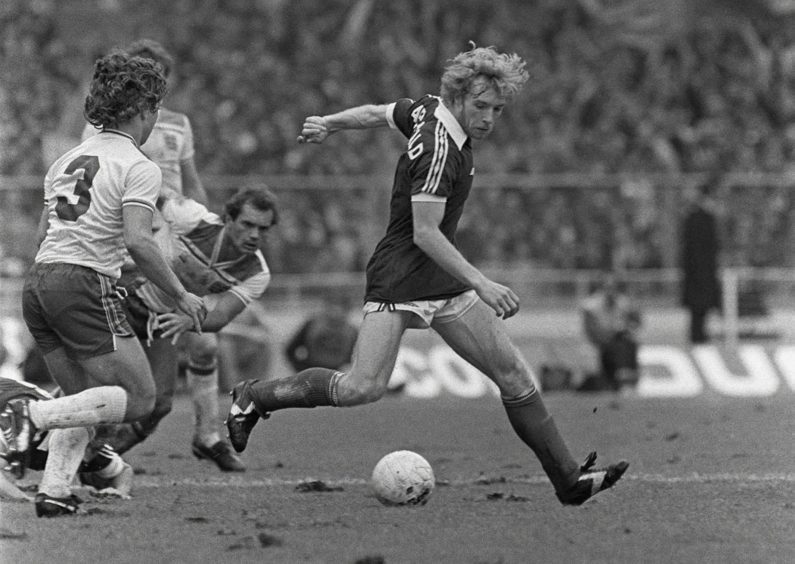

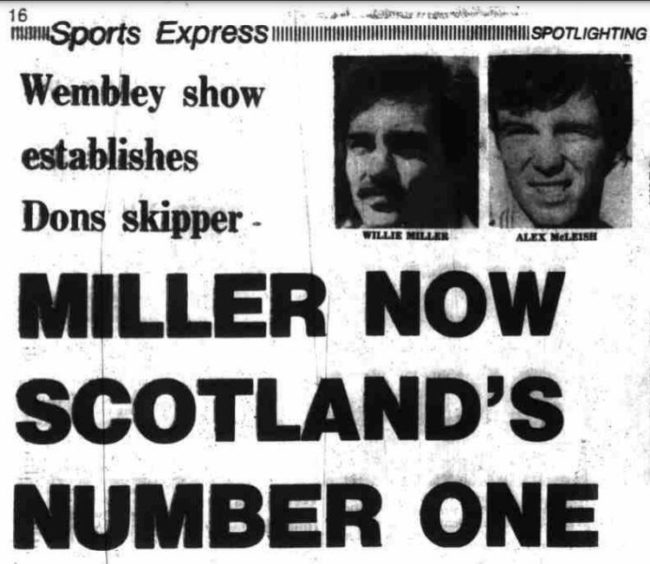

It was warm and the pitch surface wasn’t great. Willie Miller and Alex McLeish made a good start for Scotland and were commended early on for their dynamic defence.

Miller’s “fierce but fair tackling halted quite a few English moves just inside his own half”.

The Scots nearly scored in the 13th minute and again five minutes before half-time, but the uneventful first half finished goalless. Hartford was taken off with a dislocated elbow and replaced with Dundee United’s David Narey in midfield.

England – Corrigan, Anderson, Sansom, Wilkins, Watson, Robson, Coppell, Hoddle, Withe, Rix, Woodcock. Subs – Statham, Bailey, Martin, Mortimer, Francis.

Scotland – Rough, McGrain, McLeish, Miller, Gray, Provan, Stewart, Hartford, Robertson, Jordan, Archibald. Subs – Thomson, McQueen, Burns, Narey, Sturrock.

Referee – R.Wurtz (France)

England nearly took the lead, but “with 62 minutes on the clock, Scotland’s best player, Willie Miller, saved their bacon when Corrigan hooked a net-bound Withe header off the line”, the report continued.

But just minutes later Steve Archibald was pulled down by England’s Bryan Robson and a penalty was awarded.

It was Scotland’s John Robertson who stepped up to the spot, having been released from his club Nottingham Forest for the fixture.

When club games coincided with internationals, players had to be given permission to play.

His Nottingham Forest teammate Trevor Francis, who was playing for England, ran to goalie Joe Corrigan to warn him which side Robertson normally would place the ball.

It was a futile move.

“Two minutes later the Tartan Army went wild with delight when Scotland scored from the penalty spot. Robertson showed how penalties should be taken when he tucked the ball past Corrigan in expert fashion.”

The 1-0 win over England during a jubilant weekend on May 23 1981 was Scotland’s first clean sheet since at Wembley since 1938, and put the Scots at the top of the table.

Young Aberdeen players Alex McLeish and Willie Miller were lauded by Scotland manager Jock Stein for an “outstanding” performance for the national side.

The praise was echoed in the press; Miller hailed as “Scotland’s number one” after a magnificent Wembley debut, while McLeish was described as the best central defender in Britain.

Evening Express sports reporter Alastair Guthrie said in 1981: “Willie Miller stands today as Scotland’s No.1 choice for a sweeper after a magnificent Wembley debut.

“England threw their top two highly-priced strikers, Tony Woodcock and Trevor Francis, at the Aberdeen captain. But Willie was not only their equal, he was their master.

“And Miller’s Pittodrie partner McLeish again took another opportunity to show why he will retain the Scottish No.5 jersey for the next decade.

“If there is a better central defender in Britain then he has yet to be pointed out to me.”

Akin to alter boys

But it wasn’t just the players who received plaudits – “London was stunned” when there was “no vandalism, no damage along the routes to Wembley and little brawling”.

The Tartan Army – whose “behaviour was akin to alter boys” according to one commentator – proved Ted Croker wrong.

This time, the only invasion was two fans who were found hiding in the ladies’ lavatories in an early morning search before kick-off.

The police officer who found them remarked: “At least they were both wearing kilts, so I suppose it was alright.”

And afterwards, “the fans waved their yellow and red flags, flaunted their tartan shirts , scarves and Tam O’Shanters, and cooled off in the fountain at Trafalgar Square”.

The police were expecting a riot of “unbridled revelry” on the trains home, but admitted there were fewer arrests that night at Euston Station than there was on the average Saturday night.

'So you tried to ban us Mr Croker' English FA failed to ban Scotland from Home Championship. Scotland won! #NewBhoy pic.twitter.com/8iZN9dpdNp

— HomeNationsOfficial (@homenations) February 1, 2016

Acknowledging the improved conduct, Ted Croker said: “As far as I’m concerned matches between England and Scotland will certainly continue on the evidence of today’s behaviour.

“I don’t think there are any doubts that we will be at Hampden next year.”

While Mr Croker was optimistic about the Home Championship’s future, what started off as a promising contest for Scotland and the young Dons in 1981 ultimately ended in stalemate.

The unfinished championship

The tournament was rendered void due to the escalating problems in Northern Ireland with England and Wales still unwilling and unable to complete their final fixtures in Belfast.

For the first time in its almost 100-year history the British Home Championship was called off during a competition.

It was the only season apart from the two world wars that no winner was declared and 1981 went down in history as the unfinished championship.

While Scotland might have felt robbed of the chance to gain some silverware as the only team to complete all their games, it did gain Aberdeen’s Miller and McLeish international recognition

Miller’s performance at Wembley saw him go on to earn 65 caps and play at two World Cups.

But by now, the writing was on the wall for the British Home Championship.

It was already felt the tournament had outlived its usefulness with clubs increasingly holding onto players for international duties and the hooliganism did it no favours.

And on the political landscape, there was no resolution in sight for the divisions in Northern Ireland.

A century after it was established to bring the four nations together, the championship was abolished in 1984.

The final game ended in a 1-1 draw between Scotland and Northern Ireland, but the latter won on goal difference.