Aberdeen earned the nickname ‘the boom and bloom city’ in the 1970s after the discovery of oil and record-breaking back-to-back Britain in Bloom wins.

The Granite City with the floral heart proudly holds 14 gold Britain in Bloom titles to date, but not everyone was as thrilled with its run of success in the early years.

With a global reputation for its flower displays, Aberdeen has long been considered the flower capital of Scotland even before the days of national competitions.

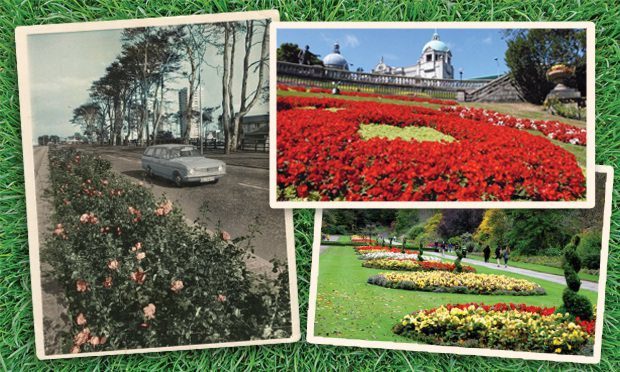

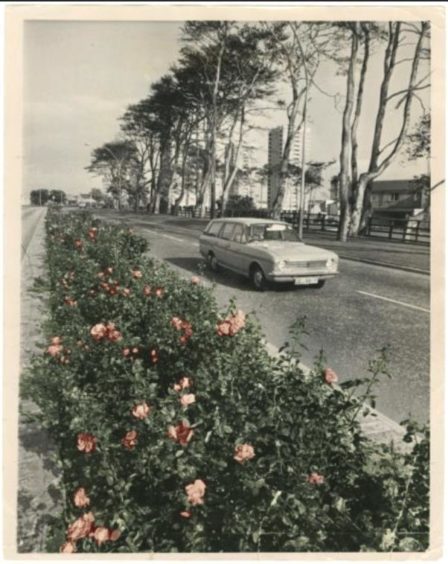

Many Aberdonians will fondly recall the beautiful roses that once lined the otherwise dull verge on Anderson Drive.

While the city’s 14 carefully-cultivated parks have provided green oases in the Silver City for the enjoyment and escapism of residents for generations.

And every spring, Aberdeen bursts into life with daffodils and colourful crocuses blanketing the banks of the River Dee.

Not forgetting the large-scale floral displays in Union Terrace Gardens depicting the city’s Bon Accord crest and coat of arms – a cheerful greeting for passengers as trains pull into the station nearby.

With such eye-catching floral flourishes – and the efforts of green-fingered residents – there was no question that Aberdeen would enter Britain in Bloom when it started in 1963.

It was introduced by the British Tourist Board, a precursor to VisitBritain, inspired by a similar successful civic competition in France to encourage communities to look their best.

The competition – which was taken over by the Royal Horticultural Society in 2002 – invites different categories of villages, towns and cities to enter.

Regional “in Bloom” campaigns, such as Beautiful Scotland, pick the cream of the crop to put forward for the RHS Britain in Bloom finals.

Ahead of the arrival of judges in the Granite City in 1964, Aberdonians were told that “garages and the entrances to schools, farms, factories and houses can be made picturesque” with trees and flowers.

Britain’s Bloom City

The hard work eventually paid off when Aberdeen was first crowned “Britain’s floral city” in 1965 – and the judging panel was unanimous in awarding Aberdeen the top trophy.

Having toured and scrutinised committees across the four nations, judges “particularly commended the imaginative use of every available corner and unoccupied plots to grow flowers, trees and shrubs”.

The city’s parkkeepers were praised for rallying surrounding communities, with “remarkable” support noted from retailers, churches, corporate bodies and “above all the rank-and-file Aberdonian”.

And the days of spiked railings and ‘keep off the grass’ signs were gone – Aberdeen was praised for opening up its green spaces and removing barriers such as tall hedges and fences.

And the success was largely attributed to the imagination and enthusiasm of the city’s director of parks, the aptly named Mr Winning, who along with its citizens had “done the city very, very proud”.

In 1966, a special Festival of Flowers was held at Westminster Abbey, London, as part of the historic building’s 900th anniversary celebrations.

As Britain’s “Bloom City” the previous year, Aberdeen was to lead the prestigious, global celebration of flora – and was put firmly on the map as the flower capital of Scotland.

A party, including green-fingered citizens, shopkeepers, park superintendents and Lord Provost Norman Hogg, travelled to the capital laiden with Scottish flowers to decorate the Abbey.

Aberdeen continued to do well in the Scottish awards taking the trophy every year, but it was 1969 before the city was supreme champion at the national contest again.

The win came the very year that storms ruined gardens and damaged the Victorian Winter Gardens glasshouses at Duthie Park beyond repair, but the city still triumphed.

Too bloomin’ good

After a run of success at Britain in Bloom – including a hat-trick of wins from 1969-71 – there were reported to be “murmurs of discontent” from other regions.

Granite City dignitaries might have been delighted that they seemed to be taking home the top trophy most years, but eyebrows were raised elsewhere.

And in 1972, Aberdeen was conspicuously absent from the British finals of the prestigious horticulture competition.

To this day, rumours remain that Aberdeen was handed a decade-long ban for being “too bloomin’ good” for the annual Britain in Bloom contest.

One commentator said the city was so superior it practically “voted itself out of the contest”, but in truth, Aberdeen was just a victim of its own success.

In February 1972 a press conference was held in Aberdeen to break the news to residents that the city would not be progressing to the Britain in Bloom finals that year.

Winners of trophies in the Scottish awards had previously gained automatic entry to the United Kingdom competition, but sensing wider resentment, the British Tourist Authority brought in a new rule.

Following the city’s hat-trick, it was decided that any community which had won the national trophy two years in a row would not be eligible to win again the following year.

Although the rule applied to all entrants, Aberdeen’s continued success saw it excluded more frequently than other competitors, creating the illusion that the city was “banned” entirely.

Convener of the city council’s parks and recreation committee, Councillor A Collie said the move was disappointing, but added: “There was no doubt the authority was under some pressure.

“I think this has been boiling under the surface and there have been murmurs of discontent. But, we are glad to accept the decision as it will help to keep the competition alive.

“We are looking forward to competing next year.”

And true to form, as soon as it was allowed to compete again in 1973, the city went out of its way to bring home gold again.

The city council planted more than 250,000 roses in streets and parks, while the resurrected Duthie Park Winter Gardens’ splendour left visitors “wide-eyed with astonishment”.

And it was the roses that helped the city smell sweet success once again in the competition, not just in 1973 but the following year too.

But of course, the rules meant the Granite City couldn’t re-enter for a third time in 1975.

Coming up roses

Yet another title win in 1977 was attributed to the work and vision of David Welch.

A celebrated horticulturist, he was appointed as the city council’s director of leisure and education in 1967.

Mr Welch ruffled feathers when he arrived at the city council and said he wanted to replace turf with more attractive, and less high maintenance, roses.

And the city reaped the rewards of his floral foresight.

But modest Mr Welch explained that Aberdeen, even before his time, had been a pioneer in cultivating parkland for the people.

Speaking in 1977, he said: “Aberdeen has always been a beautiful city and it has a distinguished tradition in parks. Aberdeen was the first to let people walk on the grass.”

He felt more could be done to enhance Union Street, an argument not unfamiliar today, and he fielded criticism of the council’s generous spending on its green spaces.

He added: “The problem is, many local authorities have many priorities and one is to ensure that everyone can lead as full a life as possible in as attractive a place as possible.

“The department’s work is not just a frill, it is more important than that.”

Mr Welch’s efforts blossomed once more when the city took home its eighth trophy – “the longest-running award-winning saga in the country” – in 1979.

It was joked at the winners’ ceremony that it would “return to what must be a well-worn spot in the Lord Provost’s office”.

The flower of Scotland

Aberdeen’s Bloom ban remains a popular urban myth, but the RHS has confirmed that the city was never barred from the competition.

Kay Clark, RHS community development manager, said: “Aberdeen has always been such a brilliant ‘Bloom’ city and we don’t have a mechanism for banning anyone.

“In recent times, rules for groups entering the UK finals stated that if an entry won their category they would not be able to re-enter the UK finals the following year.

“These sorts of breaks helped to give other communities the opportunity to enter.”

Indeed, Aberdeen won the national Britain in Bloom title again in 1987, with several Beautiful Scotland accolades in-between.

The city has been firmly rooted as “the flower of Scotland” and has continued to do so in recent years, taking the RHS’ top gold medal again in 2006, 2014, 2016, as well as the prestigious Champion of Champions in 2017 and 2018.

Covid-19 nipped all gardening shows and competitions in the bud last year, but far from being banned, Aberdeen finds itself up for award success in a scaled-back contest this year.

The Granite City has been shortlisted in a variation of the Britain in Bloom competition for 2021 – the RHS Community Awards.

The virtual awards will replace the annual Britain in Bloom finals this year for the first time in the campaign’s illustrious 57 year history.

This year, the focus is on recognising the efforts of 63 community groups across the UK – including Aberdeen Communities Together – in their work to transform their local areas.