A new plaque has been unveiled in Prague to mark the heroism of an Aberdeen-born Gordon Highlander and his colleague, who helped save the city from the Nazis in 1945.

Lucy Hughes, the British deputy ambassador to the Czech Republic, led the ceremony to commemorate the actions of William Greig and Thomas Vokes during the Prague uprising which led to its liberation on May 9 1945.

The plaque honours the gallantry of a north-east soldier in what sounds like the script from a Commando comic and recounts the story of the young private who suffered captivity, escaped from the enemy, and was the hero of the hour by making a desperate radio broadcast to help prevent a historic city from being devastated.

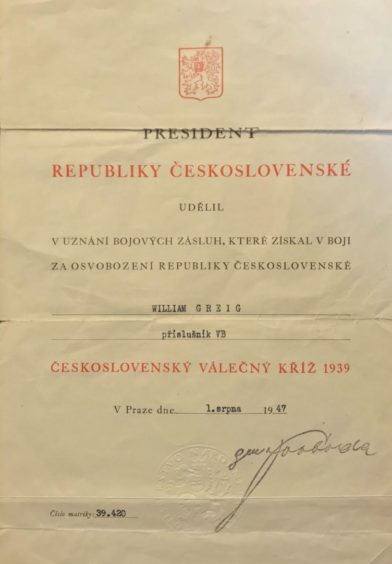

His family have also donated a medal to the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen and have explained the remarkable fashion in which Pte Greig helped rescue Prague from the German army and became the recipient of the Czech Military Cross for his courage while joining resistance fighters during the climactic stages of the Second World War.

Until now, little was known about his decision to make an urgent radio appeal to the Allies from the Czech National Radio Station.

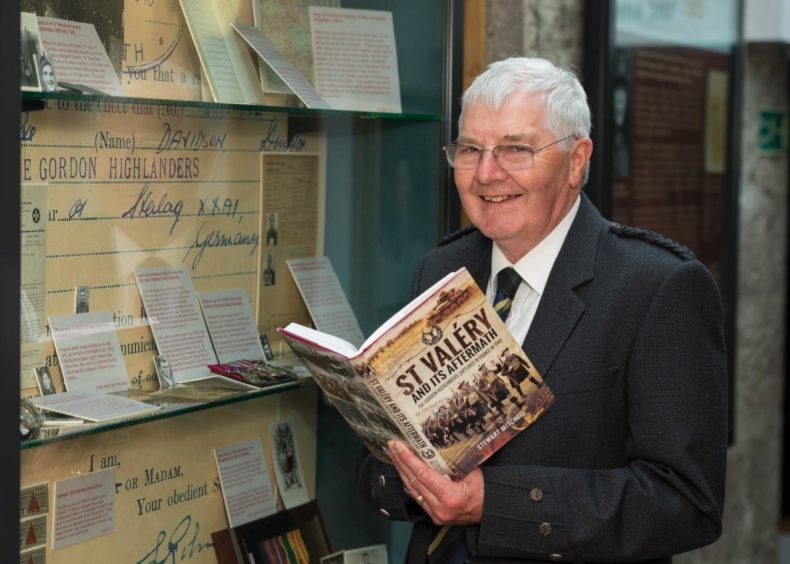

This was in response to a German onslaught in the dying days of the hostilities and Stewart Mitchell, the volunteer historian at the museum, told the Press and Journal about his admiration for the fashion in which Pte Greig responded to a series of grievous setbacks during the conflict.

He explained how Greig – who lived with his parents in Logie Avenue in Aberdeen – had joined the Gordon Highlanders on August 10 1939, a few weeks before the conflict started. He was only 17 years old, but soldiering was in his DNA, because his father had also served with the Gordon Highlanders during The Great War.

Ill-fated collective

After his basic training at Gordon Barracks in Bridge of Don, he was posted to the 1st Battalion which was with the 51st (Highland) Division in France.

However, this was the ill-fated collective which was trapped at St Valery-en-Caux and forced to surrender to General Erwin Rommel in June 1940.

In an instant, the north-east teenager became a prisoner of war and it must have felt as if history was repeating itself because his dad had suffered the same fate more than 20 years earlier.

Pte Greig, along with thousands of other Scottish soldiers, the majority of them from the north and north and north-east of Scotland, were force marched through France and Belgium and after reaching Holland, were packed into cattle wagons and transported by train to prisoner of war camps in Poland and Germany.

In his case, this was Stalag 344 (Lamsdorf) and Stalag 8A (Gorlitz) where he endured four years of imprisonment, forced to do hard labour, including at a quarry at Konigswalde, which was close to the Czechoslovakian border.

By that stage, the Germans might have imagined they had knocked the stuffing out of their adversaries, given their often brutal treatment.

But although the young Scot had been incarcerated for nearly all his adult life, and was malnourished after surviving principally on a diet of turnips – which he hated for the rest of his life – his resilience was undimmed.

Mr Mitchell said: “One day in early 1945, while they were being marched to work, Bill Greig and his friend, Tommy Vokes, from Kilmarnock, seized an opportunity to hide under bushes before rolling into a ditch to escape.

“While on the run, they foraged for food, while spending several nights sleeping rough in a cemetery, until they were befriended by a Czech family who took them in.

“They fed them and gave them civilian clothes before taking them to a railway station and putting them on a train to Prague. Here, the two escaped men were looked after by another Czech family.

“While they were in Prague, which was occupied by the Germans, Bill Greig worked with the Resistance as a courier, carrying messages between groups which was extremely dangerous work, particularly as he didn’t speak Czech although he had picked up some German while he was a POW.”

SS troops refused to surrender

Mr Mitchell added: “The war was almost over, but in Prague, a unit of fanatical SS troops had refused to surrender. The local partisans, aided by many of the population, tried to liberate their city.

“The partisans were only lightly armed, but on May 5, they gained control of the radio station. However, it didn’t take long for German forces who were assembled outside Prague to rally to the aid of their Nazi comrades in the city and it seemed as if it would become a battleground involving the destruction of many historic buildings.

“Bill Greig and Tommy Vokes were both involved in guarding the radio station. The broadcasting equipment was kept in a small room along a tunnel where Bill spent many hours lying flat with his rifle pointing at the door at the tunnel’s entrance.

“With him being a native English speaker, he agreed to broadcast an appeal to the Allies for assistance. Bill was certainly not accustomed to being involved in public speaking, so he was extremely nervous when the microphone was placed in front of him, and his mouth suddenly went dry.

“But he stiffened himself, cleared the frog in his throat and spoke; fully mindful that his broadcast could save one of Europe’s most iconic cities and thousands of its citizens.”

His oration began: “Prague is in great danger. The Germans are attacking us with tanks and planes. We are calling urgently our allies to help.

“Send immediately tanks and aircraft. Help us defend Prague. We are broadcasting from the broadcasting station. Outside there is a battle raging.”

It was one of those momentous occasions where a nation held its breath and waited to see who was listening and what their reaction would be.

And while Pte Greig’s speech might not have boasted any Churchillian rhetoric, it had the desired effect in the days ahead.

Mr Mitchell added: “Fortunately, Bill’s appeal was heard by the American military, which sent planes to destroy a column of German panzer reinforcements who were heading into the city.

“Bill’s broadcast was even heard in Britain and his mother, back in Aberdeen, heard it and recognised the voice of her son, which she hadn’t heard for years.

Military Cross for bravery

On May 9, the Red Army entered Prague and the city was saved as the prelude to jubilant scenes among the Czech public and the resistance movement.

And thereafter, as a means of commemorating Pte Greig’s critical part in saving the city in its hour of utmost danger, the Government of Czechoslovakia awarded him the country’s Military Cross for what they described as his brave and significant action.

Once he was back in his homeland, Pte Greig married Ann Milne Rose in 1947 and the pair were together for 60 years until his death in 2007.

They had three children and his son William said: “I am very proud of my father’s bravery in a situation where most would be looking to avoid further conflict after four tough years in one of the Nazis’ notorious POW camps.

“He was always a very modest man and refused to accept he was a hero.”

He was one of the generation who didn’t regard themselves as special. But that doesn’t mean the rest of us can’t take a few moments to applaud him.

It’s planned that the Gordon Highlanders Museum will re-open to the public on June 12, following extensive refurbishments.

Further information is available on the Gordon Highlanders website.