An abandoned, underground illicit whisky still was the last thing workmen expected to find when excavating an Aberdeen city centre street in 1912.

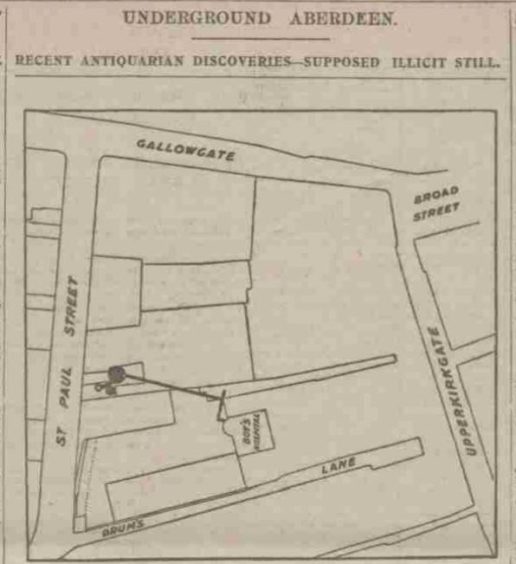

One of Aberdeen’s lost addresses, St Paul Street ran alongside Upperkirkgate off Gallowgate before it was demolished in the 1960s and 70s to make way for developments.

But in 1912, an old house on St Paul Street was being converted into a car workshop and workers were digging down to create an inspection pit when they uncovered a large slab.

Curious, the workmen lifted the stone, only to find a strange, “hive-like” chamber filled with water.

What lay beneath?

Readers of the Press and Journal might have thought they were being fooled when the discovery of a huge, underground chamber was reported in the paper on April 1.

But the stories were quite true – once the water had been pumped out, a network of chambers and tunnels were revealed below the slab.

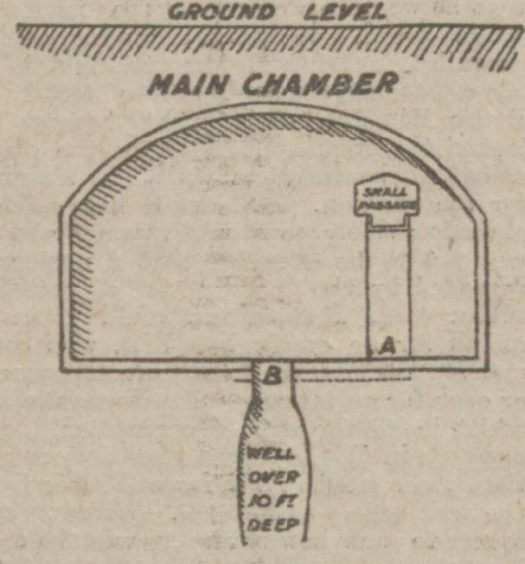

A void of almost 8ft (2.4m) led further underground into a brick-lined chamber about 10-and-a-half feet (3.2m) in height.

Investigators found the floor was paved in bricks, with little channels that drained towards a well in the centre.

A set of steps lead to an even larger chamber, about 15ft wide and 9ft 4in high (4.6m by 2.8m).

Again, the large space had drainage channels leading to a deep hole in the centre.

An even bigger channel passed under the bricks from the hole to a flue, and was found to be sooty inside.

Upon greater investigation, it was discovered the passage extended to about 85ft (26m) underground, the ends closed off by buildings erected after the tunnel was abandoned.

Digging deeper

Investigators were convinced that workmen had unearthed an abandoned illicit whisky still from the 18th Century.

But did someone really risk the wrath of the authorities and excisemen by distilling whisky under their noses, just streets away from the city jail?

Owners of the building which hid the tunnel, paint manufacturers Messrs Farquhar and Gill, invited officials from the Town Council to inspect the find.

In a letter to the Press and Journal, one investigator called Dr John Milne wrote: “I have examined the underground chamber recently discovered on the west side of St Paul Street.

“A large lump of black flint from a chalk quarry was found in excavating the rubbish filling the tunnel.

“The well, the flue, and the long passage and other appearances suggest that the chamber had been used for making whisky secretly, without paying tax to the government.

“The lump of flint had been used for procuring light by striking it with a piece of steel and causing a spark to fall into a horn containing tinder.”

Further investigations were carried out and in May, one reported that “the large chamber might have been a place for steeping malt”.

It also answered questions as to how the distilling process could take place secretly underground with no visible clues such as smoke above ground.

Adding: “The processes go on best when the weather is neither too warm nor too cold, and in the winter it is desirable to have the means of warming the barley in the germinating stage.

“This seems to have been accomplished in the big chamber by putting into the mouth of a central hole a vessel filled with red-hot malt cinders, which burn without giving off smoke.

“A stone quern, useful for grinding malt, was found above the ground in the neighbourhood of the underground chambers.”

Escaping excisemen

Documents and deeds relating to the historic property revealed an intriguing past.

Before 1744 the house was owned by a stone mason who may have made the underground works.

It was later owned by a merchant, but interestingly in 1822, documents showed it was then in possession of an officer of excise at a time when the duty on whisky was very high.

Excisemen, or gaugers, were revenue officers who worked on behalf of the government to inspect goods and raid suspected illicit stills.

The premium on whisky dated back to the 17th Century, when the Scottish Parliament realised how lucrative the new industry was.

In 1644 whisky taxes were introduced, which only encouraged the illicit distilling of whisky across Scotland.

Those discovered to be engaging in the illegal industry and not paying taxes would find themselves in court with hefty fines – or worse, in prison.

The landscape of rural Aberdeenshire, Moray and the Highlands leant itself particularly well to illegal distilling with hidden peatbog bothies and secluded but and bens.

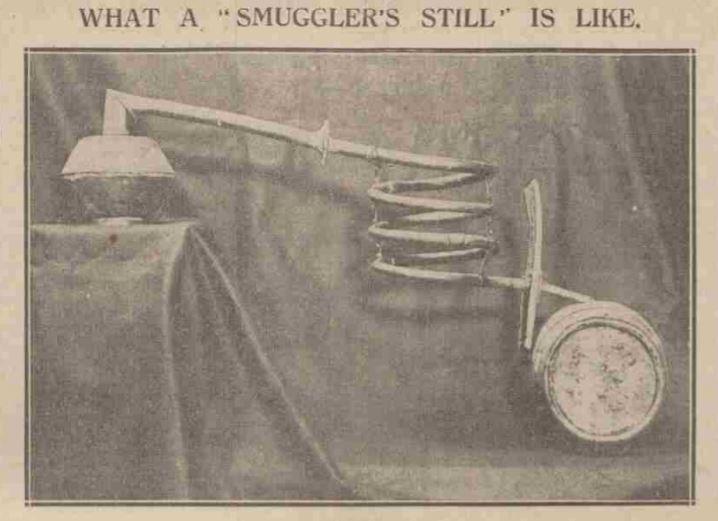

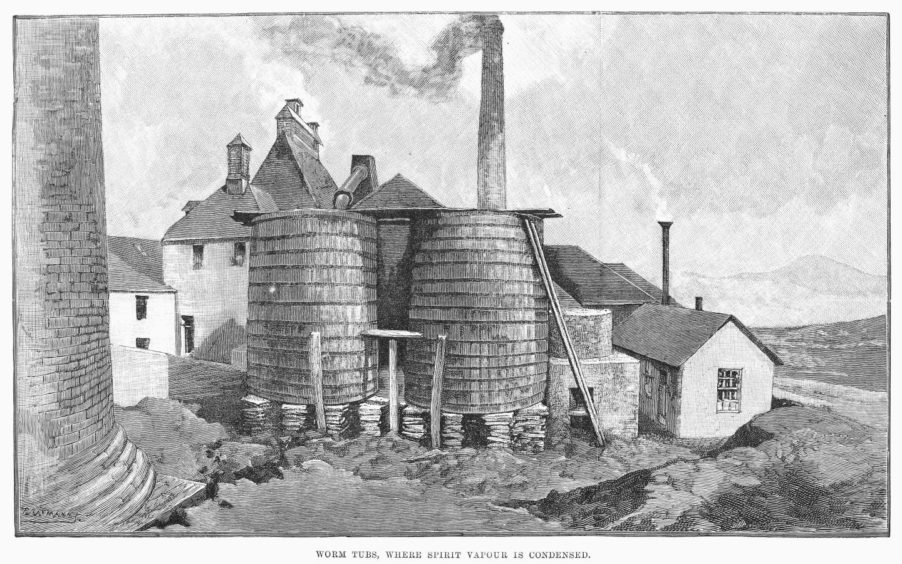

The secret stills – with large copper pots and often primitive pipework – would produce whisky from fermented grain mash.

The goods would then be smuggled along old military roads in rural parishes by whisky gangs.

Women and children were also involved in the covert trade directly under the noses of government excisemen during the Georgian era.

There were even reports of men of the cloth hiding whisky in pulpits – who would ever suspect the righteous reverend of the rural parish?

The cloak-and-dagger action seemed to work – distilling was rife.

Parts of Moray such as Glenlivet and the Cabrach were particularly notorious for their illicit whisky stills.

Tales of clandestine deeds from the Cabrach included the successful smuggling of whisky into Aberdeen in a coffin on a horse-drawn horse.

And it was estimated at one point that Glenlivet “had 500 sma’ stills in the area” before the passing of the Excise Act allowing small-scale distilling in return for a £10 licence.

Even King George IV sampled the illegal wares of one Glenlivet distiller George Smith during an 1822 state visit such was its reputation.

The following year, when the Excise Act was passed, George Smith became the first legal distiller in the parish, and the Glenlivet whisky is still produced to this day.

Other theories about chamber

Not everyone agreed that the mysterious chamber in Aberdeen was an illicit whisky still, though, and a number of other theories were put forward.

Writing to the Press and Journal, another investigator Mr William Smith suggested that the void had a less glamorous purpose.

He said it was “nothing more or less than a big cesspool” for historic mansions or a boys’ hospital that once stood nearby, because it was strongly built and watertight.

Mr Smith thought the side chamber would carry liquid away, while the end passage would act as an overflow.

Another theory offered in 1912 was that the chamber had been an old brewhouse where a maltster carried out his business in bygone times.

In more recent times, a large-scale archaeological excavation of St Paul Street took place in the 1970s.

As well as revealing “remarkable evidence” of the mediaeval period, old brick chambers were documented as part of the dig.

Aberdeen City Council archive holds no documentation on the subterranean structures, but suggested they may have been part of an ice house on the site dating from the 18th Century.

The mysterious chamber and St Paul Street are long gone, the Bon Accord Centre now stands on the site, but the intrigue lives on.