He was the Aberdeen man who sank a German U-boat, defied being injured more than 70 times, and flew himself and his comrades back to Sullom Voe during the Second World War.

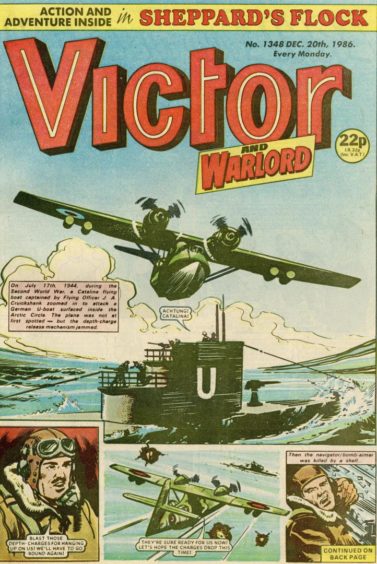

It sounds like a Boy’s Own storyline, yet while there was nothing comical about the ordeal faced by John Alexander Cruickshank during a mission over Norway in 1944, they were highlighted in a Commando-style cartoon strip in the 1980s.

The former Aberdeen Grammar school pupil, who celebrates his 101st birthday today, was involved in one of the most audacious acts of the conflict when he flew his Catalina aircraft through a torrential hail of flak.

And, although his first pass was unsuccessful, he brought it around for a second sortie, this time straddling a U-boat and sinking the vessel.

However, the German anti-aircraft fire proved fatally accurate in response, killing the navigator and injuring four others, including both Flight Lieutenant Cruickshank and second pilot, Flight Sergeant Jack Garnett.

The Granite City pilot, who was just 24, suffered scores of different injuries while he and his comrades were engaged in sinking the German submarine, and, although their had succeeded in their first objective, there was another huge task in trying to return home safely to Shetland.

Beating the odds in desperate circumstances

From a distance of more than 75 years on, it still seems miraculous that Flight Lieutenant Cruickshank was able to survive in the hours which followed.

He was hit in 72 places, and suffered serious lung injuries and 10 penetrating wounds to his lower limbs. Yet, despite this panoply of pain, he refused medical attention until he was sure that the appropriate radio signals had been sent and the aircraft was on course for its home base.

Even at that stage, he eschewed morphine, aware that it would cloud his judgement and potentially jeopardise the rest of the men on board.

Flying through the night, it took the damaged craft five-and-a-half hours to get back to Sullom Voe, with Flt Sgt Garnett at the controls and his colleague lapsing in and out of consciousness in the back.

Eventually, though, as another major hurdle came into the equation, he returned to the cockpit and took command of the aircraft.

A safe landing after a night of hell

There was nothing straightforward about ensuring the Catalina’s passage homewards; it had been impacted badly along with the crew members.

But, after deciding that the light and the sea conditions for a water landing were too risky for his inexperienced colleague, Flt Lt Cruickshank kept the craft in the air for as long he could, circling for an extra hour, as the prelude to bringing it down successfully on the water and ferrying the plane to an area where it could be safely beached.

It was an astonishing act of bravery, and yet Mr Cruickshank has always shunned the limelight or refused to take any credit for his actions.

As one of his RAF colleagues later recalled, he felt he was one of the lucky ones to survive the conflict, unlike so many of his RAF friends who perished.

Praise abounded for this selfless character

The Press and Journal reported on Saturday September 3 1944 how Flt Lt Cruickshank had become the recipient of the Victoria Cross.

Under the headline “Aberdeen hero wins V.C”, it carried the details of the citation which outlined why he had been given the honour.

This read: “This officer was the captain and pilot of a Catalina flying boat which was recently engaged on an anti-submarine patrol over northern waters.

“When a U-boat was sighted on the surface, Flying Officer Cruickshank at once turned to the attack.

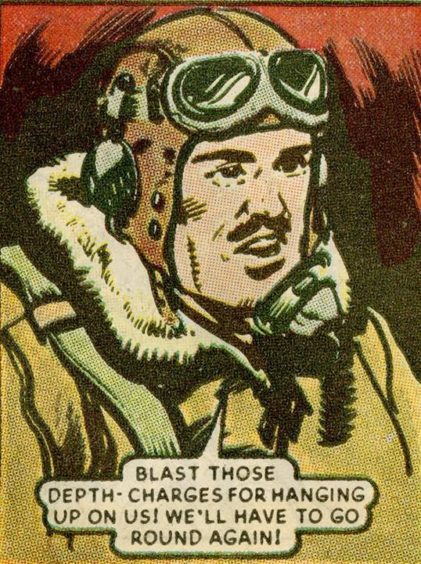

“In the face of fierce anti-aircraft fire, he manoeuvred into position and ran in to release his depth charges. Unfortunately they failed to drop.

“Flying Officer Cruickshank knew that the failure of this attack had deprived him of the advantage of surprise and that his aircraft offered a good target to the enemy’s determined and now heartened gunners.

“Without hesitation, he climbed and turned to come in again. The Catalina was met by intense and accurate fire and was repeatedly hit. The navigator/bomb aimer was killed. The second pilot and two other members of the crew were injured.

But they carried on doing their duty

“Flying Officer Cruickshank was struck in seventy-two places, receiving two serious wounds in the lungs and 10 penetrating wounds in the lower limbs. His aircraft was badly damaged and filled with the fumes of exploding shells.

“But he did not falter. He pressed home his attack, and released the depth charges himself, straddling the submarine perfectly. The U-boat was sunk.

“He then collapsed, but recovered shortly afterwards and, though bleeding profusely, insisted on resuming command and retaining it until he was satisfied that the damaged aircraft was under control, that a course had been set for base and that all the necessary signals had been sent.

“During the next five-and-half hours of the return flight, he several times lapsed into unconsciousness owing to loss of blood. When he came to, his first thought on each occasion was for the safety of his aircraft and crew.”

It could all have ended very differently

The report continued: “Although able to breathe only with the greatest difficulty, Flying Officer Cruickshank insisted on being carried forward and propped up in the second pilot’s seat.

“With his assistance, the aircraft was safely landed on the water. He then directed the taxying and beaching of the aircraft so it could easily be salvaged.

“When the medical officer went on board, Flying Officer Cruickshank collapsed and he had to be given a blood transfusion before he could be removed to hospital.

“By pressing home the second attack in his gravely wounded condition and continuing his exertions on the return journey with his strength failing all the time, he seriously prejudiced his chance of survival even if the aircraft safely reached base. Throughout, he set an example of determination, fortitude and devotion to duty in keeping with the highest traditions of the Service.”

The quiet man never wanted any fuss

Mr Cruickshank reached his personal century last May, but it was typical of this self-effacing individual that he sought privacy rather than publicity.

It was left to other people such as Aberdeen Lord Provost Barney Crockett to pay their tributes to a man who was born just after the creation of the RAF.

Mr Crockett said: “John Alexander Cruickshank has shown the sort of selfless courage and dedication to duty which should make everybody feel proud of his service.

“I would like to wish John a very happy birthday and thank him for everything he did during the Second World War and being awarded the VC.

“It was typical of him that, despite receiving more than 70 injuries, he was more concerned about his comrades and ensuring they all got home safely after their mission.

“I have met John, he is a man with an outstanding intellect and he was able to explain how his actions fitted in with the whole Allied strategy in the war. It was a privilege to talk to him.

“He is from a generation which has never sought the spotlight. But he deserves all our thanks and good wishes.”

One last postscript from a night in Aberdeen

Those of us who attended the First World War commemorative production Far, Far from Ypres at His Majesty’s Theatre in Aberdeen in 2018 could scarcely have imagined we had a real-life hero in our midst.

But sitting there, in the audience, was John Alexander Cruickshank, who appeared rather abashed when the MC announced he was present.

One of his friends said later: “I had the privilege of meeting him at a dinner and it was an unforgettable experience for everybody who was there.

“There was a stunned silence for 45 minutes while he spoke, because everyone present recognised the incredible bravery which he had demonstrated.

“And yet, one of the things which struck us was that he didn’t want a big fuss made about it. After everything he had endured, when he regained consciousness in the Catalina, the first thing he said was: ‘How are my crew?’”

No wonder everybody in the HMT auditorium gave him a rousing reception!