There’s a Peanuts cartoon strip from 1971 which features Linus talking to his best friend Charlie Brown.

In the second frame, he looks with some mystification straight in front of him and remarks: “Bob Dylan will be thirty years old this month”.

At which point, Charlie turns to him and gazes with a forlorn expression – before responding: “That’s the most depressing thing I’ve ever heard”.

The pay-off reflected a widespread feeling that the times they were a-changing as 1960s Flower Power, idealism and the Summer of Love gradually mutated into 1970s cynicism and disillusionment.

From Kennedy to Nixon in a decade.

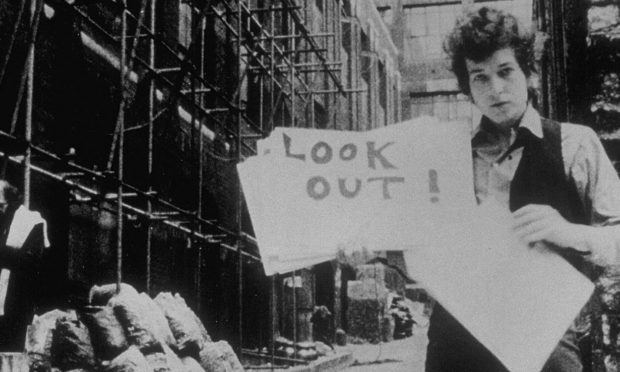

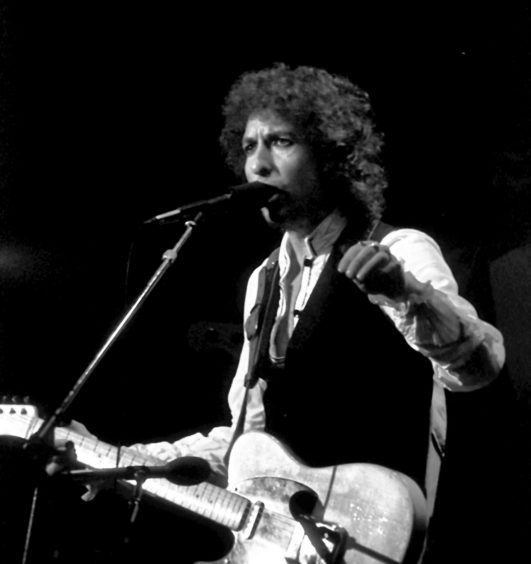

But, half a century on, the world is about to pay homage to Dylan, the serried troubadour, who created such a rich body of work and will celebrate – or at least acknowledge – his 80th birthday on May 24.

Even if it’s a milestone which the publicity-shy singer-songwriter will be inclined to leave blowin’ in the wind, his myriad fans will have reason to cheer, while reminding themselves of the quality of such timeless classics as Like a Rolling Stone, Mr Tambourine Man, Lay Lady Lay, A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, Maggie’s Farm and Shelter from the Storm.

Not least in Scotland, a country with a definite attachment to Dylan.

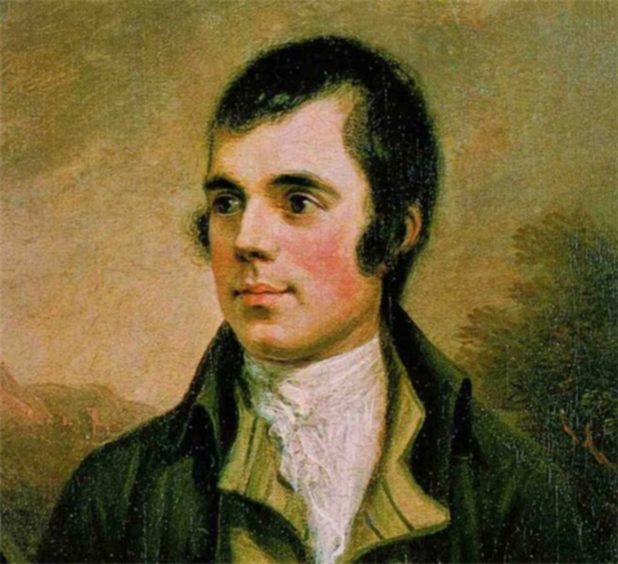

Dylan loved the songs of Robert Burns

The link between Robert Burns and America’s most renowned songwriter originally emerged during the My Inspiration advertising campaign, organised by the HMV store, which asked a variety of A-list musicians and artists to select a line or verse which had provided their greatest inspiration.

David Bowie picked a stanza from the song Gigolo Aunt, from Syd Barrett’s second album.

Liam Gallagher chose a verse from Oasis’s own hit Supersonic -penned by his brother Noel – and Paul McCartney plumped for a line from Dylan’s She Belongs To Me.

But, as for the man born Robert Allen Zimmerman in 1941, whose influence was named by so many others as their main source of inspiration and who reluctantly accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, his choice were some lines from the classic Burns work A Red, Red Rose.

O my luve is like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.As fair art thou, my bonny lass.

So deep in luve am I;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

Till a’ the seas gang dry.”

Chris Waddell, one of the team members at the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum in Alloway, told the National Trust of Scotland why he thought Dylan might have developed such a close affinity with the bard.

He said: “As a Dylan fan myself, it’s a very exciting connection. I think the thing with Burns is that he finds a place in different cultures, different hearts. He is in with the bricks in American culture; because if you think about it, he has been there for 200 years.

“There is a statue of him in Central Park in New York; Burns is taught in the school system; there are statues of him in college campuses; and we know that Abraham Lincoln kept a copy of Burns’s work on his bedside table.”

Dylan, a master of language and melody, has never explained further why he was captivated by Burns. But the Caledonian connections are there in his songs for those prepared to pursue the links.

A burst of Highland passion from Bob

There is the symphonic song called Highlands, which featured on his 30th album Time Out of Mind in 1997.

It is Dylan’s longest known studio recording at 16 minutes and 31 seconds and the echoes of his love for Scotland could hardly be clearer.

The song’s title is borrowed from the poem My Heart’s in the Highlands by Burns and, once again, the lyrics speak for themselves.

Well my heart’s in the Highlands gentle and fair

Honeysuckle blooming in the wildwood air

Bluebells blazing where the Aberdeen waters flow

Well my heart’s in the Highland

I’m gonna go there when I feel good enough to go.”

One music legend talks about his love for another

Hamish Stuart, one of the founder members of the Average White Band, who subsequently played and toured with Paul McCartney in the 1980s, has been among Dylan’s most fervent aficionados for the last six decades.

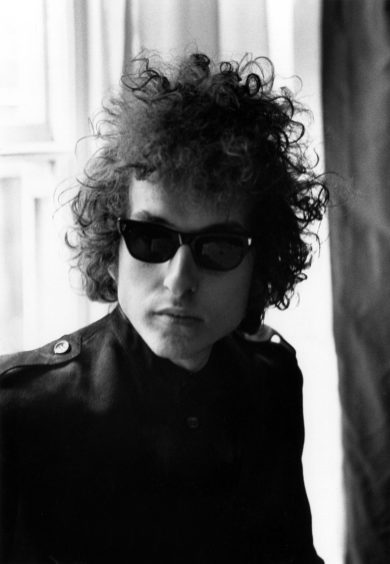

And, as far as he is concerned, the American is a giant in the business, a rugged individualist who has always blazed his own trail, whether experimenting with different genres, creating stream of consciousness prose or, more recently, recording a jazz album which didn’t so much divide the critics as skewer them to pieces.

Not that he has ever cared about reviews or critics or pandered to the anoraks who pore over his lyrics with pointless obsession. Simon and Garfunkel may be famous for The Sound of Silence, but it’s their compatriot who has dwelt in the shadows, living more like Greta Garbo than Freddie Mercury.

‘We really believed we could change the world’

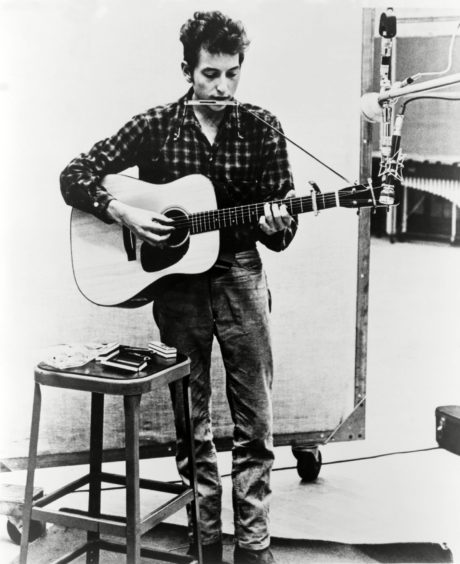

Hamish said: “I was introduced to Bob through George Wilson, a guy in secondary school who pooh-poohed The Beatles and promoted the significance of Dylan.

“The Times They Are A-Changing struck a chord with me and I explored further by buying The Freewheeling Bob Dylan and the subsequent albums.

“The songs like Masters of War, A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall and Blowin’ In The Wind really chimed with what a lot of my generation were waking up to with the civil rights movement and the threat of nuclear war.

“Then he went electric and freaked out the folk purists, making classics like Positively Fourth Street and the epic Like A Rolling Stone.

“The list goes on and on. I kind of lost track of his music as I got more involved in my own, but classics would still pop up like Knocking On Heaven’s Door and Hurricane [the latter was about the wrongful imprisonment of the boxer Rubin Carter]”.

Dylan was influential in the civil rights movement

Hamish added: “I only saw him perform ‘live’ once when he played Hammersmith Odeon nigh on a decade ago and he had a great band, playing some of the classics and, unlike shows I had heard about from others, he stayed true to the melody of the well known ones, with Ballad Of A Thin Man and Forever Young being the standouts.

“It’s not an urban myth that [political activist] Malcolm X told Sam Cooke about The Times They Are A-Changing.

“He may even have played him the record in a move to encourage Sam to write more politically and A Change Is Gonna Come was the result. Anyway you cut it, he remains hugely influential and important.

“Even when you move forward to his most recent work [Rough and Rowdy ways], Murder Most Foul is an epic track and chillingly brings back the horror of the assassination of JFK.

His voice isn’t the important thing about Dylan

“He is still an influence for me, not stylistically, but from a pure songwriting point of view and the fact that some of his slightly more obscure songs can be taken and made relevant by the likes of Adele (To Feel My Love) is a testament to the enduring nature of a lot of his work.

“Those early protest anthems from the 60s are relevant again given recent history. The times are still a-changing but not fast enough.

“In reference to Bob’s ravaged voice, myself and my oldest friend from school have been lifelong fans and, when he went to see Dylan a while back, I asked him how the voice was. He replied: ‘It was great, he used both of his notes!”

Dylan himself has no lofty opinion of his vocal talents, but he once remarked: “I was never a good singer, but if you have a good story, then it doesn’t matter because people want to listen.”

He knows he commands a global audience. As Hamish concluded: “It is still Himself and The Beatles who absolutely set the tone and the standard.”