Les Wilson admits he was amazed when he started researching the history of tea production – and discovered a caddy-load of farmers and planters from the north-east of Scotland were in the brew.

He has delved into the backgrounds of those who travelled from such places as Laurencekirk, Inverness, Dundee, Banff, Kingussie and Aberdeen to risk their lives in developing the drink as an international commodity: a venture which led to so many Scots getting involved in foreign climes that the Ceylon Observer started publishing articles in Doric.

And there are some genuinely jaw-dropping revelations in his new book Putting the Tea in Britain about the Scottish impact on the industry in far-flung parts of China, Asia and India during the 19th century.

It brought rewards to many of these men, their families and their companies, but there was a dark side to the trade which caused wars, was the catalyst for the virtual enslavement of native peoples, boosted the production and distribution of hard drugs and often caused environmental devastation.

The seeds of an idea were sown by Scots

Mr Wilson was intrigued by the story of Archibald Campbell, a doctor and keen amateur botanist from Islay, who was the first person to grow tea in Darjeeling after graduating in medicine from Edinburgh University.

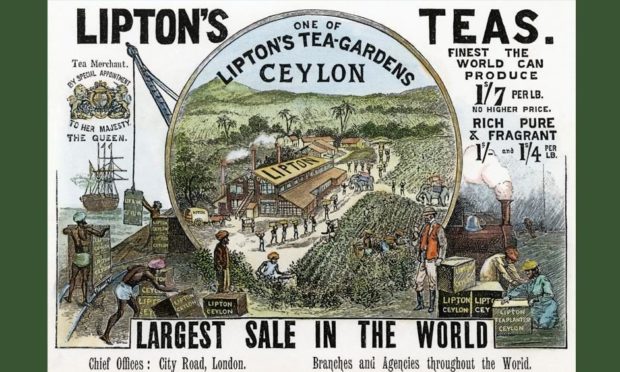

His inspiration soon sparked many of his compatriots to follow in his footsteps, including James Taylor of Kincardineshire, who dragged the economy of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka] back from the brink of disaster; Robert Kyd, an Angus-born soldier, who founded Calcutta’s botanic garden, where tea was first nurtured in India; and Thomas Lipton, who brought affordable tea to the masses and orchestrated the situation where more than 165 million cups of the liquid are currently consumed every day across the UK.

As Mr Wilson said: “The list of medics I encountered reads like both like a professional directory and a gazetteer of Scotland – Campbell of Islay, Falconer of Forres, Roxburgh of Symington, Buchanan-Hamilton of Callander, Jameson of Leith, Govan of Cupar, Hooker of Glasgow and Wallich of Denmark (but with an Aberdeen University medical degree).”

Some of these men were innovators, while others spotted opportunities to expand their horizons (and bank balances), but they were all prepared to journey halfway across the world. And the cumulative impact was staggering.

James Taylor remains esteemed in Sri Lanka

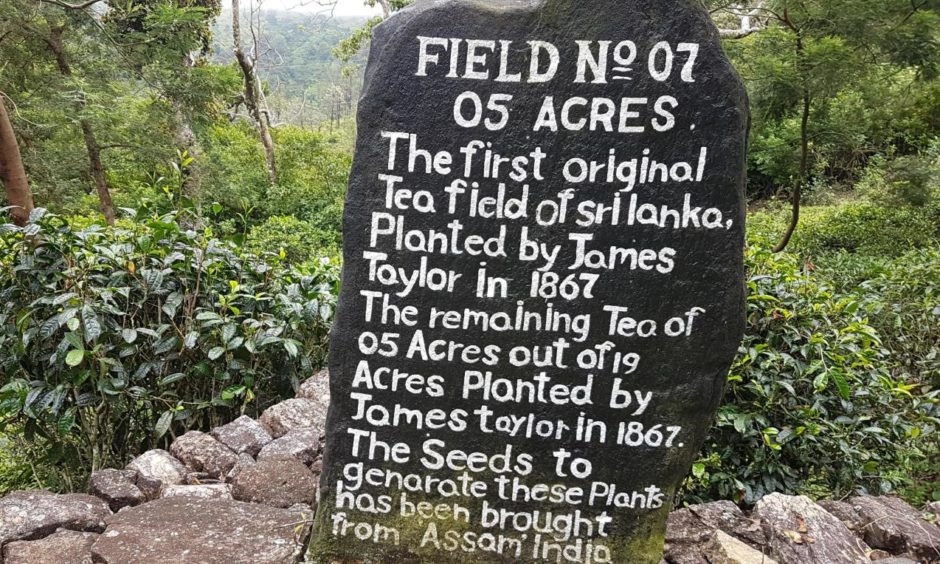

James Taylor from Auchenblae was one of the most mercurial figures, who worked with indigenous people in Ceylon, where his name is still cherished.

Mr Wilson said: “This is a man who is forgotten in Scotland – but revered in Sri Lanka. He was 16 in 1851 when he sailed to Ceylon to start work as a ‘creeper’ – a trainee estate manager on a coffee plantation.

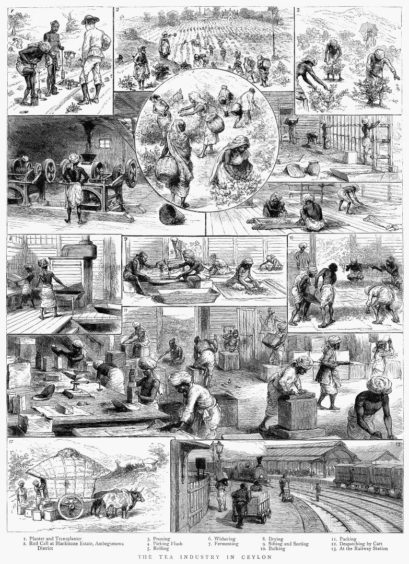

“He had a very lively mind and was a keen self educator and when he became manager at Loolecondera Estate in the highlands near Kandy, he began experimenting with tea as a crop. In the next few years, a fungal disease swept through Ceylon’s coffee plantations, and the colony faced ruin.

“But Taylor had shown the way – and his skill as a tea grower saved Ceylon from ruin when other planters followed his example, grubbed out their dead coffee bushes and planted tea in their place. Thanks to James Taylor, Ceylon became one of the great tea regions of the world.”

He added: “Banff man Henry Brown – who has also been forgotten – had fled Ceylon when the coffee crop was destroyed by disease and went to what is now East Africa to take a job as an estate manager.

“While walking in the garden of the Church of Scotland mission in Blantyre in what is now Malawi, he spotted a tea bush that had been planted as a specimen plant by the mission gardener.

“He scrounged a pocketful of seeds, planted them on the estate he managed – and set Africa on course to become one of the great tea regions of the world.

“I knew quite a bit about Scotland’s disproportionate role in running the British empire, and had long been aware that many Scots had been tea planters, but I had no idea that the early pioneering work on tea was so dominated by Scots.

“I was amazed to find it was a Islay man who had first planted tea in Darjeeling – and this prompted my investigation. And then to find that Scots were responsible for breaking China’s tea monopoly, for Assam tea, Ceylon tea and African tea made me realise I had an incredible Scottish story to tell.”

Not everybody profited from the industry

Just as in the North American Gold Rush, some people accumulated vast wealth from their enterprises, but many others lost everything.

An abundance of young Scots travelled to Asia and Africa with grand ambitions which were cruelly dashed by a combination of disease, tropical conditions, or lack of business acumen in a febrile commercial market.

The death toll of these young planters and family members makes grim reading. Martin Fraser of Laggan died at 21, Margaret Jolly, the wife of a Laurencekirk man, at 26, David Bell of Dundee at 32, Alex Lumsden and George Baxter Wilson of Aberdeenshire at 21 and 22, Robert Arnott of Inverness at 33, Donald Bain of Kingussie at 33…and so the list continued.

Others perished in accidents, from sunstroke, cholera and malaria or in peculiar circumstances. One Scot, James Souter, was fatally struck by a cricket ball. Another, John Spottiswood Robertson, was one of seven Europeans known to have been killed by elephants between 1815 and 1833.

There was the prospect of amassing vast wealth, but, as with so many other aspects of Empire, the grim spectre always existed of young men and women being buried far from home with their dreams destroyed.

The Doric stories hit the press in Ceylon

The 1840s were a boom time not just for tea, but coffee as well and Scots were as instrumental in that international expansion.

Robert Tytler, from Peterhead, was among those who journeyed to Ceylon, aged just 18, to jointly manage a company which was manufacturing coffee estates and many others followed in his wake.

As Mr Wilson said: “So numerous were the north-easterners that the Ceylon Observer carried articles in the Doric dialect. One such essay, titled ‘How I Lost my Wattie’, was attributed to ‘an auld Scotchman’ and described coffee planting life in the 1840s.

“It tells of a young Peterhead man’s rise and fall in Ceylon. He wrote: ‘Tae be plain and practical, my widowed mither saul out [sold] o’ the fairm left us by oor faither an wi £1,500 o’ the proceeds comin tae my share, I determined wi this tae become a laird o’ a coffy estate.’

It was a gruelling existence, but many of these hardy Scots thrived and James Taylor is still regarded as “The Father of Ceylon Tea”.

His story is among the most remarkable, because he achieved so much so quickly after being a pupil/teacher at Fordoun, prior to ignoring his family’s wishes for him to settle down with a bride and a solid job in Scotland.

As Mr Wilson explained: “[Coffee worker] Peter Moir pulled the strings that allowed Taylor and another of his mother’s cousins, Henry Stiven, to sign up for jobs on the Ceylon plantations.

“The cousins’ voyage took 122 days, and their ship dropped anchor off Colombo on February 20 1852. While owners came and went, Taylor spent the rest of his days at his beloved Loolecondera estate. Although manicured, emerald-green tea plants, not forest, cloak the hillsides today, the wide glens and craggy peaks of the estate remind the traveller of Highland Scotland.

“Visiting the estate in the 1960s, the writer Denys Forrest was also struck by the similarities. [He wrote] ‘It is, one feels, what tea growing in the Cairngorms would be if such a thing was possible.”

And now, as the book relates, such a thing IS possible.

Bagging a story in the midst of a pandemic

Mr Wilson has spoken to several people about the creation of tea companies in places such as Angus and Perthshire and highlighted the organisation Tea Scotland, which represents 16 different growers across the country, from Orkney to Galloway and the Isle of Arran to the coast of Fife.

Its chairman, Richard Ross, is a modern-day equivalent of James Taylor, who cultivates 700 bushes on family-owned land near Dunkeld – and his story is following in a time-honoured tradition.

As the author said: “One hundred years to the day before Richard planted his first bush, his grandfather set out from Tannadice, near Forfar, to become a tea planter in Ceylon.

“[Meanwhile] at her family farm near Forfar, Susie Walker-Munro grows her tea bushes from Georgian and Nepalese stock in a venerable walled garden, in polytunnels and increasingly outside on a loamy, south-facing hillside of the Strathmore Valley. It is a business she started from scratch and her first tea bushes had taken root before she realised that tea ran in her blood.”

One last chapter to Mull over a brew

It is a two-ferry odyssey from Lismore to Mull where Liz and Martyn Gibson cultivate about 250 tea bushes on their 10-acre croft near Craignure.

It’s often taxing work, hardly assisted by the vagaries of the Scottish climate, but the couple have already taken significant strides forward and, as Liz said: “We’re delighted to be actually growing tea on Mull, so we know it’s possible.”

Their Scottish Antler stem tea gained publicity on the global stage when it was included in a pack presented by First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to President Barack Obama during her visit to the United States in 2015.

As Mr Wilson said: “Such success must be cheering to Liz and Martyn during long, cold Scottish winter nights on the croft, and especially in the knowledge that, every year, the roots of their precious tea bushes are embedding themselves more deeply into the soil of Mull.”

Putting the Tea in Britain by Les Wilson is published by Birlinn.