It was a project which took nearly 70 years – and spanned two world wars – to bring to fruition in Peterhead.

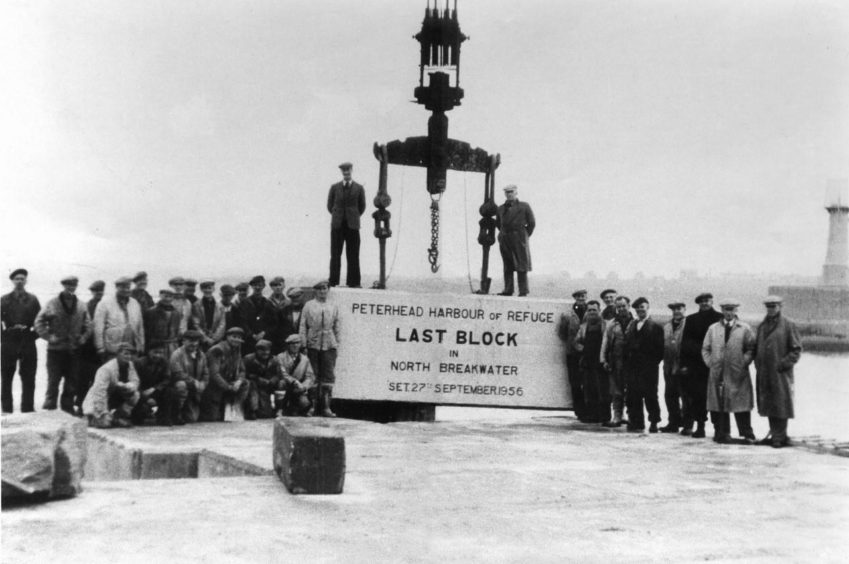

And, by the time the Harbour Refuge venture was completed in 1956, the grandsons of men who had started working on the ambitious scheme were among those who celebrated laying the last foundation block.

The initiative sparked controversy in the Victorian era with one leading north-east politician asserting the costs involved were “utter folly” and arguing it would have been better located in Stonehaven than further up the coast.

And, although it eventually went ahead in the Blue Toon, the often dangerous work claimed the lives of some who were involved in the construction process.

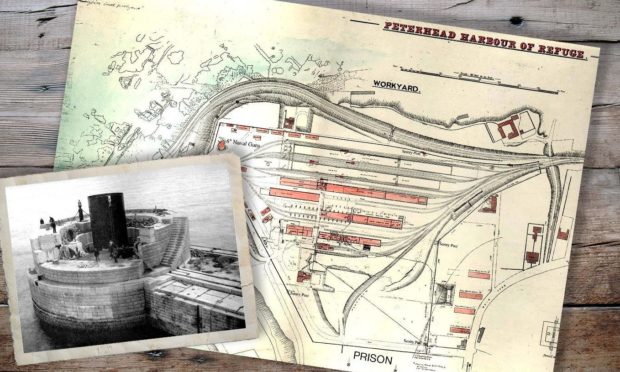

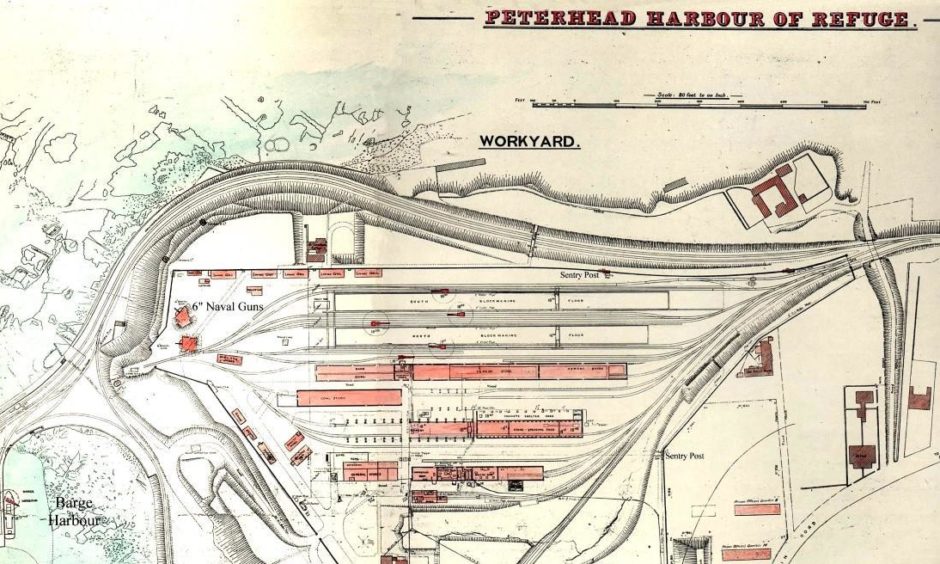

The harbour was situated close to Peterhead Prison, which now houses a popular museum – and its operations manager, Alex Geddes, has unearthed a cache of dramatic pictures and plans about this groundbreaking enterprise.

The original idea dates back to the 1850s

As early as 1858, the Peterhead Harbour trustees submitted a bid to create a harbour of refuge and engaged the Stevensons – who were most famous for their lighthouses around Britain – to draw up detailed proposals.

Mr Geddes said: “The commissioners were receptive to the idea of Peterhead as the site, but favoured the plans of one of their own engineers. Things looked good, but the money involved proved to be the stumbling block.

“The Harbour trustees would have been expected to come up with £200,000 of the cost. Which at the time, was a vast sum and completely impossible.

“Everyone seemed to agree it was a good idea, but it had hit an impasse.”

However, as decades passed, it dawned on some people that there would be a source of extremely cheap labour if convicts carried out the heavy loading.

Westminster politics entered the equation

By 1882, a positive decision was announced in the House of Parliament where it was estimated that up to 800 convicts would be available for the work and, two years later, a sub-committee was appointed to decide on the most suitable location for the construction and its adjacent convict prison.

A short list was eventually narrowed down to Montrose or Peterhead and the committee came out in favour of the latter.

But not everyone was happy. Sir John Balfour, the MP for Kincardineshire traduced the Peterhead project as “folly” and when critics alleged he was only against it because he had championed Stonehaven as an alternative site for a breakwater, he responded that £50,000 spent at five different places would provide a far better return than the total investment in Peterhead.

Yet, despite his objections, the 1886 Harbour of Refuge Act allowed the building of a prison outside the town beside Invernettie, adjacent to the Admiralty development at Salthousehead.

And Messrs D Macandrew & Co of Aberdeen were informed in October of that year that they had been awarded the contract for its construction.

Mr Geddes added: “With the land purchased for £5,000, the cost of construction was estimated at between £30,000 and £40,000.

“In keeping with the practice of the time, the contractor built the perimeter wall, with some cell accommodation and the necessary ancillary buildings of the prison. The convicts were then engaged on the completion of the rest of their cell block, which advanced to build a further cell-block. They were also employed on the building of some of the staff quarters.

“Railway lines were laid between the Admiralty yard, the Breakwater, and the Quarry at Stirlinghill from where the stone for the project would be blasted.”

The initial building blocks had been implemented and the project was finally gathering momentum.

But, even as progress was made, the hazardous nature of much of the work was highlighted by a series of tragedies, which involved both the prisoners and staff at the site.

This was harsh unforgiving work

There were regular occasions, in these days before health and safety regulations, when workers’ lives were placed at risk.

Peterhead Prison Museum has chronicled some of the accounts and they testify to the myriad dangers to which men were regularly exposed.

One report from 1894 recounted how a diver who was employed at the Harbour of Refuge Works had a narrow escape with his life.

It said: “It appears he was engaged, along with other divers, at the end of the breakwater in putting the huge 50-ton concrete and granite blocks in position after they had been lowered by the Titan crane.

“One block was being put into its bed, and the signal was given to lower away. As the block settled, it was discovered that the lifeline and a part of the air tube of one of the men had been fixed by the block, with the result that the diver was in great danger of being suffocated.

“As soon as [this information] was conveyed to the men in charge of the barge on which was placed the air-pump, the crane man was signalled to raise the block. This having been done, the diver below was released, and was drawn to the surface of the water.

“His helmet having been taken off, it was found that he was almost in an unconscious condition. But he soon came round after being rescued.”

No happy ending for the Buchan blacksmith

However, weather-related or machinery- linked incidents and mishaps around the harbour area were a frequent occurrence and there was a grim ending for one north-east father-of-eight in the summer of 1926.

As the contemporary report stated: “A distressing accident occurred about 1.30pm at the South Breakwater, resulting in the death by drowning of a workman who was employed at the Harbour of Refuge.

“The unfortunate man, James Bruce of Burnhaven was, it is understood, proceeding to the end of the breakwater, along with another employee, with the object of attending to the lamps.

“A heavy ground swell was running, and a big wave dashed over the breakwater and carried Bruce into the bay. His companion, recognising the total impossibility of affecting a single-handed rescue, quickly ran back to the works and gave warning of what had happened.

The elderly victim needed the work

“The occurrence had also been witnessed from the North Breakwater, near which the barge Thistle was lying; and the vessel at once put out to offer the man assistance. After about half-an-hour, during which Bruce succeeded in keeping himself afloat, he was got aboard the barge, but by that time, he was totally exhausted, and in an unconscious condition.

“Dr Taylor of Peterhead, was summoned to the scene, and applied artificial respiration for over an hour, but without avail and, shortly before three o’clock, it was apparent that life was extinct.

“The task of bringing Bruce aboard the Thistle was an extremely difficult one, owing to the heavy sea, but it was accomplished largely as a result of the gallant action of Robert Buchan, 30 Merchant Street, Peterhead (a member of the crew of the Thistle), who dived fully clad into the water and succeeded in getting a rope round Bruce.

“Mr Buchan has been identified with many gallant rescues, and was holder of the Royal Humane Society’s certificate for life saving.”

A poignant story emerged thereafter….

Mr Bruce, a blacksmith to trade, left behind a large family, including a five-year-old son and he had been struggling to make ends meet.

His wages were £1 and one shilling a week during the summer, but only 14 shillings a week in the winter and he had been striving to supplement his income.

One report read: “His duties involved him charging the navigation light at the end of the breakwater, which required him to ferry carbide gas bottles along the length of the breakwater.

“Two waves were responsible for Mr Bruce’s fate. One wave hit him and knocked him out, before a second rose over the wall and washed him into the sea. It is hard to imagine what a hard life it must have been for him and his wife to raise eight children on such wages and it is sobering to contemplate the reality for the family who have lost the breadwinner.”

Sadly, his demise was not uncommon. In 1893, a convict, John Hanley, 25 – the youngest of a family of 15 – perished when he fell onto rocks in Peterhead, while working at the quarry in Peterhead.

And, the following year, a fireman, John Milne, was killed and his colleague, George Milne, a foreman, was gravely injured after an explosion at Stirlinghill propelled the pair to the bottom of the quarry.

The Press and Journal from the time reported: “Part of the deceased’s clothing was found burning at a distance of thirty yards off.

“Both men were married, John Milne leaving a widow and five of a family. He was a native of Rora [a village in Aberdeenshire], and it is believed he had only recently came to the harbour works.”

In November of that year, it was confirmed that Mr Milne’s widow had been awarded a payment of £10, while her 14-year-old daughter received a one-off payment of £8, with Mrs Milne gaining a pension of £10 per annum for life.

The work was only finished in 1956

The construction process took many decades, interrupted by two global conflicts and a series of economic downturns which placed limits on how much time could be devoted to the completion of the grandiose scheme.

In these circumstances, it was hardly surprising that the workers and management were as much relieved as delighted when the last piece of the jigsaw was finally installed in 1956: almost a century after the original proposals had been drawn up by the Stevensons.

The initiative provided Peterhead with an infrastructure which protected it from the worst impact of the notorious north-east climate – and a prison, which was eventually branded the “Hate Factory” before it closed in 2013.

Prison museum will highlight harbour refuge

Alex Geddes has investigated the history of the project and while it has clearly boosted Peterhead and the surrounding area, he appreciates the sacrifices which were made throughout its construction.

He said: “The last block was laid in 1956, although it was operational way before that stage. But the reason it took so long to build was that there were two world wars and a great depression during that time, so the whole build was drastically extended because of these things.

“The two new exhibit areas [at the museum] about the railway to the quarry and the other about life in the quarry and where the granite ended up [once it left the region] will cover the links to the Harbour of Refuge development and we are keeping our fingers crossed both areas will open later this summer.”

Further information is available here.