It’s hard to imagine what was going through the mind of a World War Two German pilot as he swooped low over a playground and waved at the children- just having dropped two massive bombs on a nearby factory on the shores of Loch Ness.

Was it just a natural reaction to seeing excited children? Or was he trying to say, ‘sorry, I’m not a bad guy really?’ Or did it have a more devilish motivation?

We’ll never know, but the facts remain – 80 years ago the tiny village of Foyers on South Loch Ness was in the eye of the Nazis because it hosted an aluminium factory, built in 1895 by the British Aluminium Company.

The Highland Archive Centre holds an account of the incident, which relates that on Thursday February 13 1941, a twin-engine Heinkel came in along Loch Ness at midday, flying so low that the German airmen were clearly seen.

Two 500lb bombs were dropped and the plane turned away fast up the narrow forge of the river, then flew still low over the green and houses at Glenlia.

The pilot waved at the children who were on their way home from school for lunch.

Neither of the bombs scored a direct hit.

Anti-German sabotage at play?

One bomb was made in Czechoslovakia and perhaps some anti-German sabotage was afoot as it just touched the side of the factory but did not explode, the report suggests.

The other fell a short distance away but the blast fractured pipes leading to the generators and caused some minor damage inside the factory.

The blast was responsible, however for the deaths of two men.

Archibald MacDonald was blown into the turbine chamber while Murdo Macleod died of a heart attack.

The BBC later reported that the plane had been shot down over the North Sea.

‘The pilot circled the area flying very low above the school and waved to children in the playground’

Some 34 years later, in April 1975, commemorating the opening of the new reversible pumped storage station at Foyers, Hydro News revisited the incident with more detail.

“The bombs were fused with approximately two second delayed action fuses.”

An eyewitness told Hydro News: “It was a lovely day. One bomb struck the coping stone of the power station and went into the hillside, fracturing pipes carrying water to the turbines.

“The second bomb fell in open ground.

“The pilot circled the area flying very low above the school and waved to children in the playground.

“One man was killed in the attack, the factory returned to partial production on the following day and within a few weeks repairs were complete.”

He has found the police records of the incident, featuring Constable Colin Ross who was on duty at the time.

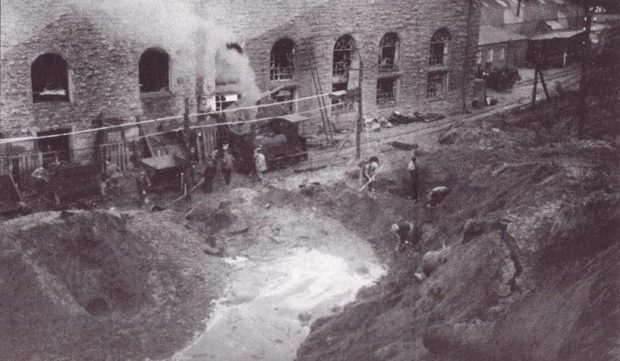

PC Ross headed for the factory and noted that the bombs had fallen in sandy soil on top of the pipeline, causing a massive crater 30-40ft from the east wall of the dynamo room.

It fractured five water pipes, damaging the furnaces in the furnace room with sand and water from the burst pipes.

Mr Morley writes: “In addition, all the windows from the factory buildings, post office and dwelling houses were shattered and electric overhead cables and telephone lines were destroyed.

“In the Roman Catholic chapel, some 250 yds away the blast was so powerful it had completely blown out seven windows.”

Repairs began immediately, but “the human cost was sadly more substantial,” records Mr Morley.

“In the immediate aftermath of the raid, Foyers GP Dr Gamble, Nurse Alison and several volunteer first aid personnel established a first aid dressing station at the factory where they began to treat casualties.

“At this time only one fatality was recorded, that being Murdo MacLeod, 69, furnaceman of 35 Glenlia who had ‘died from shock following the explosion.’”

Some workers had sustained serious injuries, including resident manager Herbert Skelton who had skin wounds to his forehead, foreman Donald Fraser of Clubfield House who had an injury to his left foot, foreman fitter Duncan Ramsay of 60 Glenlia who had a back injury, and John MacMillan, labourer, Elmbank hut, who had to be taken to the Royal Northern Infirmary by car with a severe injury to his ankle and foot.

Other workers were treated for minor cuts due to flying glass.

Fitter found missing

But it was three hours after the raid that people realised that Invernessian fitter Archibald MacDonald, 7 Elmbank Terrace, was missing.

Mr Morley said: “ A search was conducted and at 6pm his badly mutilated body was found famed between the inside of the wall and the driving wheel of no.1 turbine machine in the turbine pit about 10ft below ground level.

“Archibald MacDonald’s body was recovered to the dressing station where he was examined by Dr Gamble who stated that death was due to ‘multiple injuries following enemy action’.

“It was thought that MacDonald was walking along the railway track a few feet from where the bombs fell and was hurled into the turbine pit by the force of the blast.

“Death would have been instantaneous and not by drowning in the turbine pit as stated in some accounts.”

His death notice in the Inverness Courier reads: “Many in Inverness learned with regret of the death through enemy action of Mr Archibald Macdonald of 7 Elmbank, Foyers, about 53 years of age, native of Inverness, son of late Mr and Mrs Macdonald of 39 Madras Street. He served in last war and had been employed at Foyers for past twenty years.”

He was buried in Tomnahurich cemetery and was survived by a widow, a son and a daughter.

The unfortunate Murdo Macleod had his funeral in Boleskine. He was a native of Ullapool, and well known in Foyers district where he had resided for a long time.

He was survived by a widow, and four sons, one of who was in a POW in Germany at the time.

In the days of the pandemic we have become used to combatting a mortal enemy, albeit invisible, so perhaps we can imagine the fear in the minds of the folk of South Loch Ness- and the rest of the country- as they went about their daily business as normally as possible.

On the day of the bombing, the War Cabinet announced: “The war has moved into a new stage involving the utmost gravity. What the future has in store is not precisely clear, but it is essential there should be no delay or doubt about the need for preparedness.”

Elsewhere there were unsubstantiated reports of German troop movements in Bulgaria and Romania.

Fascist General Franco was meeting with Marshal Petain and Admiral Darlan of the Vichy France.

He had previously met with Mussolini, during which the newspapers reported there was “agreement in every aspect of the situation in Europe and on the re-organisation of power in Mediterranean and Africa” as the war raged on in Greece and Eritrea, Abyssinia and Somaliland.

For many families it was not only a time of grief, but great daily anguish with loved ones on the front or captive as prisoners of war.

The Inverness Courier of that day carries a letter home from ‘an Inverness officer’ in a camp in Germany.

“Reveille here is at 7.30am, 6.30 British time.

“We have black coffee, then wash, and parade at 9.30 to be counted.

“Then soup and potatoes at 11.

“After that we play bridge or walk till 4pm and again we have soup and potatoes.

“In the evenings we attend concerts, lectures, play bridge again or read.

“We get one-fifth of a loaf of rye bread per day, and lard, jam and cheese once a week.

“We are getting parcels from the British legion, Geneva.

“I’m afraid the Red Cross at home have failed to overcome the difficulties.

“We get an issue of 20-30 French, Belgian or Polish cigarettes per week.

“I am wearing a pair of Belgian boots, and now we have been issued with a Belgian overcoat.

“There is a river passing this barracks which reminds me of the Ness.”

He ends his letter with a plea for more cigarettes and tobacco.

But morale-boosting entertainment was still part of the picture on the home front.

The local papers were advertising a dance at the Caledonian hotel ballroom in Inverness- featuring Roy King and his Ballroom Orchestra, gents 3/6, ladies 3/-.

Playing in the Playhouse was The Ghost Breakers with Bob Hope and Paulette Goddard.

In La Scala Adolphe Manou and Carole Landis were starring in Turnabout.

The Empire was showing Charles Chaplin in The Great Dictator, and The Palace, Boris Karloff in The Ape.

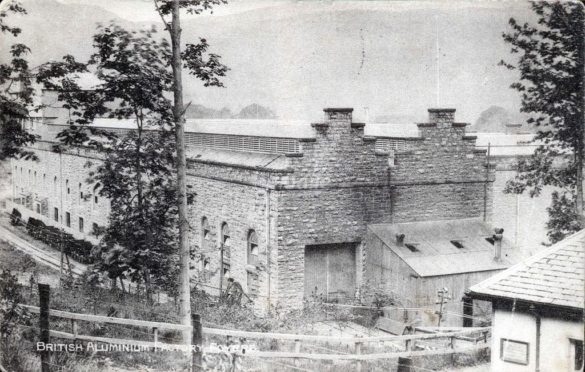

The British Aluminium Company ran until 1967 in Foyers

The company had bought exclusive rights to the Héroult process – the electrolytic method of producing aluminium – discovered in 1886 and went on to acquire the estates of Gorthleck, Wester Aberchalder and Lower Foyers, which included the spectacular Falls of Foyers.

They planned to use the water of the falls to produce cheap power for the new industry.

The factory the company built on the shores of Loch Ness was the first to produce aluminium in the United Kingdom and the first in Great Britain to use water power to generate electricity.

From the Edinburgh Evening News of Monday September 16 1895:

“Lord Kelvin, president of the Royal Society, visited Foyers a few days ago and inspected, in his capacity of their scientific adviser, the operations of the British Aluminium company. Several hundreds of men are at present employed and their number will be considerably added to within the new few weeks.

“Between £500 and £600 a week are being expended in wages. Lord Kelvin viewed with much interest: the tunnel, the laying of the huge pipes, the turbine pits, the blasting operations etc.

“His lordship regards the inauguration of the proposed aluminium works as one of the most interesting events of recent years, there being no similar factory in Britain.”

Materials were transported by boats using the Caledonian Canal and a light railway connected the wharf and the factory.

The factory ceased aluminium production in 1967.

It took on a new life in April 1975 when the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board’s new reversible pumped storage station at Floyers was formally opened by the Rt Hon William Ross MP, secretary of state for Scotland, with a capacity of 300MW.

It cost £20m, with a further £1.2m to linking it to the Board’s Highland grid, and was only the second reversible pumped storage project built by the board.