There was never any question of standing on ceremony when I visited Eric Johnston at his home in Aberdeen.

The elderly soldier may have shown conspicuous gallantry throughout the hostilities, but he refused to regard himself as a hero and even told me he “disliked” the word.

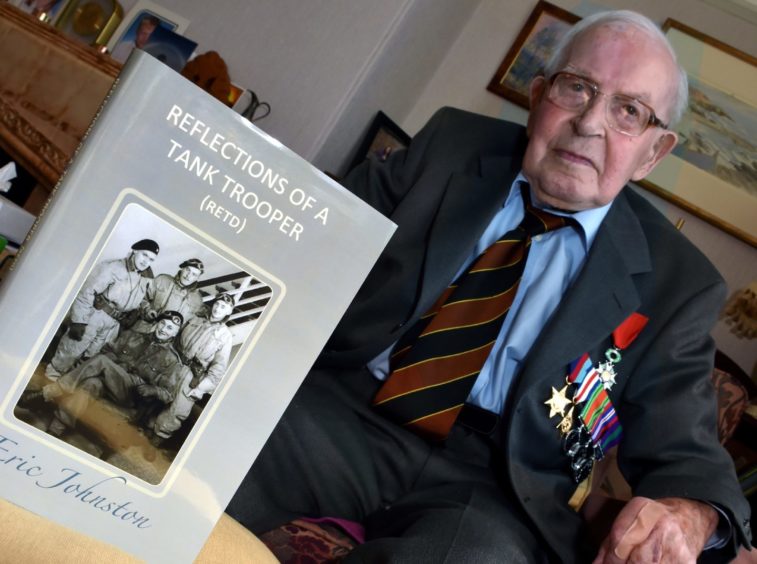

Yes, he was proud of being awarded the Legion d’honneur by the French government but only because it allowed him to salute many of his comrades who had perished on the beaches on Normandy when the Allied invasion was met with prolonged and deadly resistance by the German army.

“We were the lucky ones, who had the chance to live our lives and grow old with our families,” he said.

“A lot of boys never saw their loved ones again and that thought still makes me realise how fortunate I have been.”

Outraged at US planning for D-Day

Mr Johnston was passionate until the end – he died early in 2020, aged 96 – about the reasons why there was so much carnage in the early stages of D-Day.

He felt outrage at the terrible scale of the casualties, particularly in the American ranks during those fateful hours in June, and outlined how he and his British colleagues had benefited from being involved in meticulous planning in Moray.

As he said: “We prepared properly in advance and it helped us, though it came at a cost.

“The 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards lost tanks in Burghead Bay and Sandilands Bay while training and there was also loss of life due to rough seas.

“As a consequence, the regiment insisted that a 4/7 officer be consulted before anybody launched tanks at 5,000 to 8,099 yards off the beach.

“It was a crucial decision. The result was that we managed to make successful landings on Gold Beach on June 6 with only five tanks lost in the process.

“However, on Omaha Beach, the Americans lost 27 of 32 tanks and there was no consultation with the military before launching.

“It was ridiculous and tragic – the tanks weighed 32 tonnes and they sank immediately after leaving the tank landing craft. All those poor fellows…

“Captain Scott-Bowden, a British observer, who had previously reconnoitred the beach for the Americans, called their strategy ‘absolutely insane’.

“Instead of having tanks at 50-yard intervals covering the infantry, the latter were absolutely slaughtered on the beach.

“We can look back on D-Day as a success and a vital part of the war, but this is a story which needs to be told.”

Mr Johnston never had a rose-tinted view of the sacrifices made during one of the largest operations in military history.

But he admitted to being slightly shame-faced at recalling how excitedly he had signed up for action without thinking about its impact on his family.

He said: “I volunteered for the Royal Armoured Corps while I was on a lunch break from my job at the bank.

“I was just a teenager. I thought it would be a big adventure and I trained at places such as Fort George before joining the tank crews of the 4/7 Royal Dragoon Guards and going on active service.

“I was only 20 on D-Day with no dependants and no other responsibilities.

“Of course, I cared about my family but I knew of so many who were killed with sweethearts back home who never got the opportunity to say goodbye.

“When war broke out, my mum was in tears and I had never seen her cry before. But I was very young, very callow, naïve, I suppose, and that probably helped me get through some of the things I saw.”

The first few days weren’t too bad…

Many of the stories of D-Day, whether tragic, courageous or triumphant, have been collated by the Imperial War Museum.

They emphasise both the tremendous acts of gallantry and the visceral slaughter of troops which occurred on different beaches in Normandy.

Mr Johnston wasn’t among those worst affected at the outset.

Yet this was only the beginning of months of struggle which lay ahead in Europe as he and thousands of others encountered constant threats from the Germans – and, in some cases, their own forces.

He said: “The casualties on D-Day itself were actually fewer than expected in most cases.

“But it was the days and weeks after that which were harder and where we lost so many people to so-called ‘friendly fire’.

“I was scared at times, I feared what might happen, but everybody was in the same boat.

“You just had to get on with it and there was a sense among us that this was a war which had to be fought and had to be won.

“But it was a time of extreme danger, of battle fatigue and terrible shelling; you knew that you were in a situation where men could simply vanish when a bomb exploded so, naturally, I was very glad when it was all over.”

Eric became an author in his 90s

The book project was almost an afterthought for Mr Johnston, who was given a jolt by a colleague while they were attending a 70th anniversary function.

He said: “Back in 2014, I met up with a member of my regiment and he told me that if I had any memories, I should write them down before it was too late. So I just got on with it and it brought back a lot of memories and faces.

“The book was a labour of love for all those who didn’t come back.

“We lost so many pals, so many colleagues, whereas I was given the opportunity to return back to my family in Aberdeen and get on with the rest of my life.”

And this enterprising fellow, with a relish for sport and mountaineering and exploring his country’s wild places, packed a lot into that life.

A picture of modesty and selflessness

The old soldier, who was married to his late wife, Joan, for more than 50 years, was proud to receive the Legion d’honneur, recognising the selfless heroism and determination shown by all surviving veterans who landed at Normandy, and of the wider campaigns to liberate France in 1944.

“I never expected anything like that but all these things came from the regiment,” he said.

“I have never been one to make a fuss about what went on in the past but I suppose that if we can keep reminding younger generations of the terrible things which happened in the war, it should hopefully mean they will never have to experience it themselves in the future.”

Mr Johnston, who returned to banking after the conflict, eventually becoming an area manager with Trustee Savings Bank (Scotland), was a Burgess of the City of Aberdeen and an honorary president of the Cairngorm Group.

He was also one of 12 D-Day veterans to have his portrait painted by the renowned artist Catherine Goodman.

On my last visit to his property, just off Seafield Road in 2019, he joked about the fine job she had done, “especially considering what she had to work with”.

The picture was unveiled at Buckingham Palace and the exhibition attracted plenty of attention when it was unveiled.

Yet none of that truly seemed important to this redoubtable character. What mattered was that he and many others had stood up when they were needed and been involved in one of the defining chapters in the war to defeat Nazism.

An attitude that was typical of his generation.