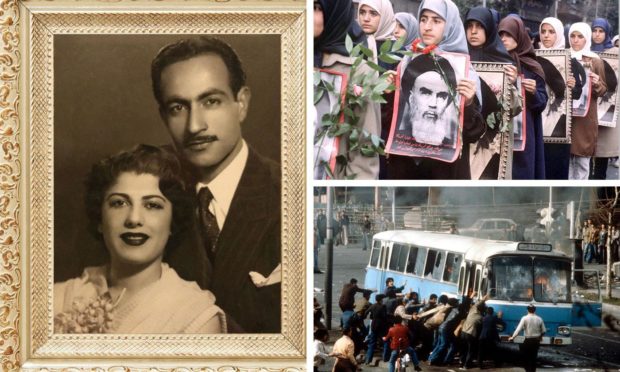

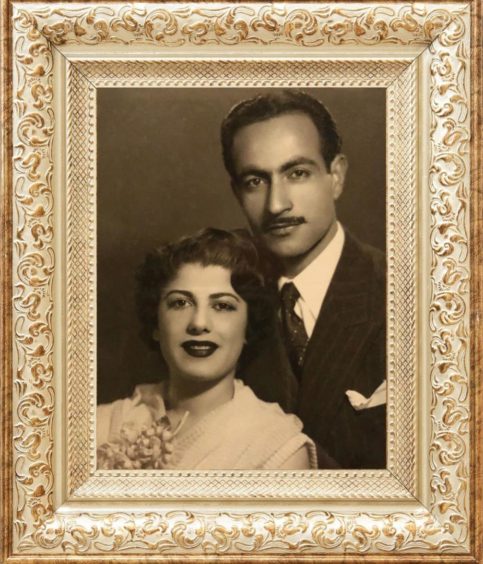

The handsome couple in the wedding photograph look serene and happy.

By rights, Mehrangiz (Mehri) and Manuchir Farzaneh-Moayyad should have enjoyed long, contented years of marriage in their native Iran, building a loving home, watching their three children grow up, playing with grandchildren, secure in their strong Bahà’i faith.

Instead, religious persecution and regime change turned their lives upside down with astonishing inhumanity.

Manuchihr was executed; Mehri was arrested, and facing execution, managed by the skin of her teeth to escape on camels across the desert with her 12 year old daughter to join her sons, sent to Scotland earlier for their education in Dundee and Aberdeen.

Mehri’s story has now been told in When Reason Sleeps (pub George Ronald) by family friend and fellow Bahà’i Audrey Mellard.

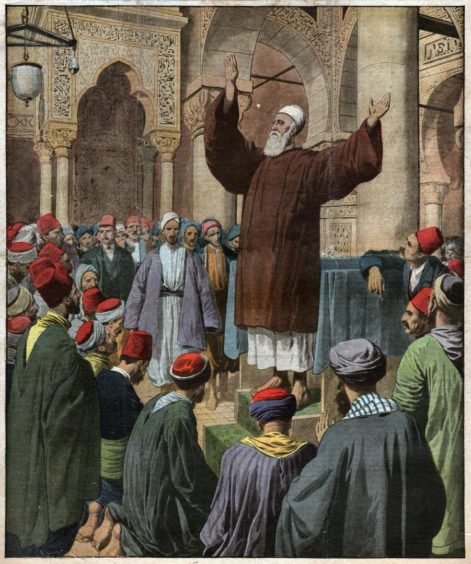

The faith originated in Iran in the mid-19th century, and teaches the unity of all people.

Persecution a daily occurrence

Audrey describes how persecution on grounds of their faith is a fact of life for the Bahà’i in Iran, with the family enduring taunts and insults on daily basis.

But for a while after Mehri and Manuchihr’s children were born, life was happy and comfortable, although always with threatening undercurrents.

They lived in Tehran, and then Qazin, Manuchihr overseeing the construction of branches of the French-Iranian Bank of Credit.

In 1979, he was transferred to Shiraz – but the family’s moved coincided with the start of the Islamic Revolution, and in light of a growing campaign against Manuchihr for his Bahà’i faith by local clerics, his employers transferred him back to Tehran for the family’s safety.

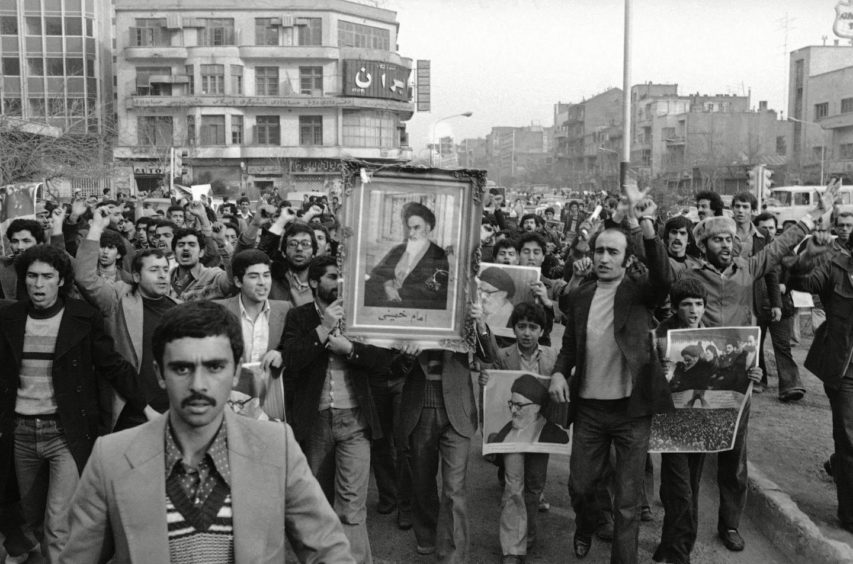

The ousting of the Shah Reza Pahlavi by supporters of the exiled Ayatollah Khomeini meant that nearly 60 years of efforts towards modernisation were swept away and the country was under the control of Muslim clerics.

Audrey writes: “On his return to Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa- a ruling on a matter of Islamic law- ordering Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians and other religious minorities which pre-date Islam to be treated well.

“This fatwa specifically excluded the Bahà’is and virtually declared open season on the Bahà’i faith.”

Unprecedented persecution ensued, with killings, torture, imprisonment, disappearances, confiscation of property, destruction of Bahà’i centres and holy places, loss of jobs and pensions, denial of education.

Manuchihr arrested and executed

In May 1982, Manuchihr was arrested and driven to the Revolutionary Court, where he was sentenced to death.

His imprisonment involved harrowing episodes of mind games and vicious torture as he refused to recant his faith.

On the night of July 9, Mehri had a strange dream which Audrey describes in her book.

It turned out to be a remarkably accurate prediction of her husband’s execution that day on charges of being an active Bahà’i.

Beside themselves, sons Farshid and Fardin phoned from Scotland, desperate to return to protect their mother and sister Shanna.

Mehri persuaded them to stay safely abroad as the persecution and executions intensified.

Other members of the family ‘disappeared’ or were executed, including one of the children’s beloved aunts.

No time to grieve

Mehri had no time to grieve or come to terms with the terrible things she found out had been inflicted on her husband.

Audrey writes: “The Revolutionary Guards visited almost daily, asking endless questions about Manuchihr’s brothers, and about business interests or property any of them might have.

“They would ‘confiscate’ anything that appealed to them, and it was during one of these visits that one of them took Shanna’s jewellery, a little gold chain and an amethyst ring.”

They also took away some red soil Mehri had gathered from Manuchihr’s grave.

“This was of no value to anyone but his grieving family and can only have been intended to add to their distress.”

Mehri arrested

Mehri’s arrest was inevitable, and came a year after the execution of her husband, on July 10, 1983.

Fortunately, Shanna was out getting milk and remained safe as Mehri was driven away.

In a Revolutionary Court prison in the north of Tehran, she endured solitary confinement and violence, with promises that it would all end if she become a Muslim.

“Mehri replied that she preferred to be a human being,” Audrey writes.

Mehri was seriously ill at this time and losing blood. She found a muddy patch in the yard where she sat for three days until the other prisoners saw fit to allow her to drink from the water tap, and but for the intervention of another Bahà’i inmate to get her on the list for food, she might have died.

Mehri sentenced to hang

Her weakened physical state protected Mehri from physical torture at this point, and for a horrible reason.

Audrey relates that the officials didn’t want her to die under torture as she might well have done.

“They wanted her strong enough to hang. Ironically it was the official insistence on a prisoner being able to stand up unaided while the sentence of hanging was carried out that was eventually to provide Mehri with the opportunity to escape from both the prison system and Iran.”

Eventually she was told to go to hospital to seek treatment, and when she remained sick, told to go away for further treatment – until she was strong enough to be hanged.

This eventually gave her the opportunity to escape with Shanna in a complex and dangerous operation with Afghani smugglers of contraband for the Mujahaddin.

Dressed in Islamic attire, Mehri, Shanna and five other Bahà’i embarked on a series of gruelling bus journeys to the desert – but that was just the start of their harrowing ordeal.

Audrey says that even to this day people who helped them cannot be named for fear of reprisals.

Their flight continued on camels

Eventually they were provided with a camel each for the next stage of their flight.

They were ill-equipped for the rigours of travelling by camel, Audrey writes.

“Mehri had never seen a camel before except in pictures, and any idea of an animal with some sort of seat for its rider was soon dispelled.

“The seven animals that made up the caravan were so heavily laden with the goods they were trafficking that there was no room for anything resembling a saddle.

“The Arabian camel offers no support for the back, only a rope to hold onto, and Shanna clutched this rope so tightly that a little gold ring on her finger was broken into several pieces.

“Any position quickly became extremely painful, so much so that when they halted for a brief rest, none were able to stand unaided.”

Their thick black clothes were also a torment in the heat.

“In countries where women are accorded a lower status than men, the men usually get to wear dazzling white, which reflects the heat and keeps the wearer much cooler , whilst the women are shrouded in heat-absorbing black, often in heavy fabrics that will not move even in a breeze.”

Shanna disappears

In a terrifying incident, Shanna and her camel disappeared, with none of the smugglers prepared to go back for her.

But after intense pleading, one did go back and after what seemed like hours reappeared with Shanna and the camel, which it turned out had simply decided to sit down for a rest and refused to budge.

A ray of light in the journey was the kind treatment of Bedouins who made sure the exhausted travellers were fed and watered.

On into Afghanistan and eventually onto trucks full of smuggled goods and with gunmen lying full length on the cargo, the fugitives crouching where they could.

Looked after by the Mujahaddin

That ordeal lasted a day, before on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, they reached a Mujahaddin camp.

Now into Afghan clothes, even more thick, filthy and uncomfortable than the previous garb, with only a mesh in front of their eyes.

The Taliban were all around, “actively suppressing whatever was deemed to be unseemly conduct by women,” writes Audrey.

Then over the border into Pakistan and a horrific ride in a dangerous, filthy, smelly overcrowded bus full of livestock and people walking literally on top of Mehri and Shanna’s heads when dismounting.

Safely in Pakistan they were delivered to the care of the local Bahà’i community.

Registering as refugees

The first thing to do was to register with the United Nations in Lahore as refugees, and get identity cards.

Granted full refugee status, Mehri and Shanna headed for Aberdeen to join Farshid, 29, and Fardin, 24.

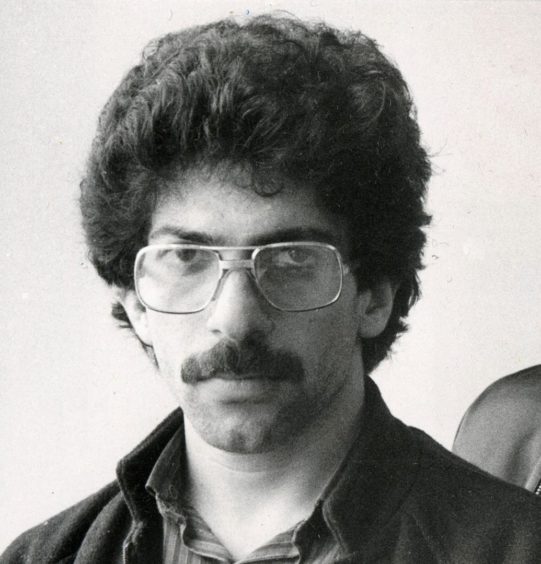

In an interview for the Evening Express in 1986, Farshid said his mother still loved Iran and hoped to return there, but she had immense gratitude to the country she fled to.

He said: “She is very grateful for being accepted in this country and for all the help she’s been given here.”

Mehri’s experiences scarred her so deeply physically and emotionally that she has been unable to live a full life since the trauma of her husband’s death and her own imprisonment and flight.

Aged 86, she’s now in the care of a nursing home.