Try to imagine the job of chronicling every player who pulled on a Scotland football jersey in the years before the Second World War.

It was a task which led to Andy Mitchell delving into the history of no less than 615 men who gained international recognition between 1872 and 1939; a Herculean effort, and especially considering the often shambolic nature of record-keeping in the early days of the game’s development.

Some of these characters changed their names and adopted pseudonyms; a number of them were born illegitimate; while others were illiterate and could not even write their name, so it ended up being recorded phonetically.

Then there was the occasion in 1898 when goalkeeper Willie Watson – born in Northumberland – and Jimmy McKee from County Down were both selected for the Scotland team which defeated Wales 5-2. It was against the rules, but summed up the often harum-scarum element of the sport in Victorian times.

These early performers came from all parts of their homeland and included everybody from successful business figures, war heroes and upstanding citizens to criminals, drunks and wife beaters.

Many enjoyed long and happy lives, but others died too soon, from the scourges of tuberculosis, alcoholism and mental illness, or from injuries which they sustained in battle, or while playing the game.

And here, we highlight just a few of the more unusual individuals from the north-east of Scotland, Tayside and Fife who were capped at least once by the Scottish Football Association.

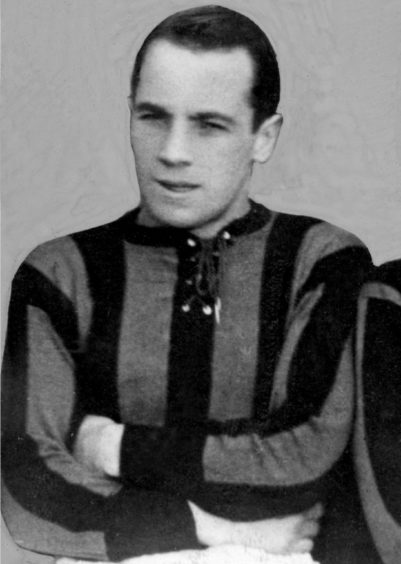

Cheyne inspired the Hampden Roar

Alex Cheyne’s career encompassed everything from playing for Aberdeen, Chelsea and Nimes Olympique to managing Arbroath and advocating better contracts and freedom of movement for players, decades before Bosman.

But he is probably most famous as the inspiration for the Hampden Roar: that spine-tingling raucous release of passionate intensity which has followed moments of triumph for myriad Scottish collectives at the Glasgow stadium.

Mr Mitchell said: “He scored direct from his trademark in-swinging corner in the last minute of the match against England on his debut in 1929 – and the resulting roar from the crowd took Scotland over the line for an unlikely win.

“Strangely, Cheyne was only in the team as a late replacement for the injured Tommy Muirhead, but, a year later, he went on Scotland’s successful tour of Europe, playing in all three matches and scoring a treble against Norway.

“Cheyne made his name as an inside right at Aberdeen, after coming north from Shettleston in 1925, and he delighted the crowds at Pittodrie.

“But he was something of a rebel, describing a football career as ‘bondage’ and was hugely critical of the wage structures and the retain-and-transfer system.”

Cheyne, who served with the Royal Armoured Corps and the RASC during the Second World War, subsequently took charge of Arbroath from 1949 to 1955 and also coached at Banks o’ Dee in Aberdeen. He died in 1983, aged 76.

A Torry man in a betting scandal

He was a pocket dynamo with a greedy-guts attitude to notching up goals, but Benny Yorston’s name is inextricably associated with scandal at Pittodrie.

Capped as a junior against Ireland in 1925, the 5ft 5in Torry-born player soon demonstrated his talents after starting his senior career at Montrose and graduated on to his home city club, where he scored more than 100 times in the league for the Dons in the space of less than five years.

However, as Mr Mitchell said: “He only won a single Scotland cap, against Ireland in 1931. But, later that year, he was one of five first-team players who were sensationally transfer-listed by Aberdeen for reasons which have never been made clear, but were probably linked to [illegal] betting and Yorston was sold on to Sunderland for £2,000.

“He found it hard to settle there, was plagued by illness, and eventually joined Middlesbrough, where he spent the rest of his career. But, during the war, he served in the Army as a Sergeant-Instructor in Physical Training, which gave him the opportunity to guest for a number of clubs, mostly in Scotland.”

After being demobbed, Yorston was released by his English employers in the autumn of 1945 and played one solitary match for Dundee United before confirming his retirement and moving to London, where he died in 1977.

His story offers ample evidence of how precocious gifts can often be squandered: and that is a sadly recurring theme in Mitchell’s new book The Men who Made Scotland. But there were many positive stories as well.

Colman’s relish inspired Aberdeen

He is now revered in Aberdeen and further afield as a genuine pioneer – the man who dreamt up the dug-out – but young Donald Cunningham was so apprehensive about how his parents might react to his passion for football that he adopted his grandmother’s surname of Colman and it stuck.

A stellar figure from the outset, he lifted the Junior Cup with Maryhill and spent two seasons at Motherwell before joining the Dons in 1907, at which point his career really took off with a vengeance.

He excelled in the right-back berth for a decade, gaining his first international cap in 1911, aged 32, which encapsulated Colman’s penchant for defying convention, on and off the pitch. He combined playing in Scotland with coaching at Brann Bergen in Norway and although he was over 40 by the time he retired, he simply brought the same enthusiasm to training at Pittodrie.

Mr Mitchell said: “He achieved lasting fame by inventing the dug-out, the forerunner to today’s bench and technical area, because he was convinced that it was the best place to watch the players’ footwork.”

Colman died of tuberculosis, aged 64, in the Granite City in 1942. But his legacy lives on and a plaque has recently been unveiled at his former residence by the AFC Heritage Trust, in association with the city council.

A master craftsman in different trades

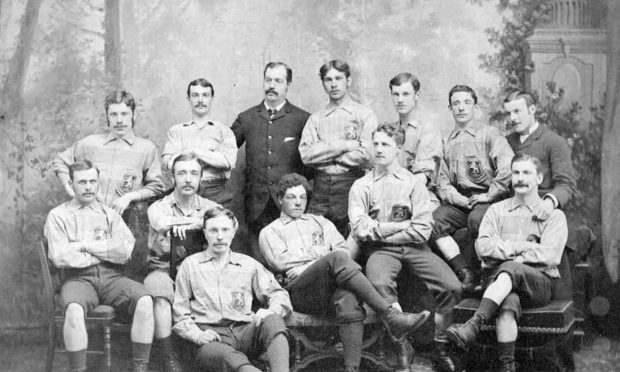

He was an acclaimed player who was once carried off the pitch by his team mates in triumphant celebrations after masterminding success over England.

Yet Sandy Keiller was one of life’s local heroes, a blithe homespun character who was content to stay close to Montrose and Dundee, despite being offered myriad incentives to move to different club organisations in England.

He turned professional in 1893, rapidly forcing his way into the ranks of the newly-formed Dundee FC, but even by that stage, had been capped twice on the left wing by Scotland against Wales and Ireland.

As Mr Mitchell said: “Although there were offers to go south, he had a steady job [as a master slater] and preferred to remain at home, which meant he continued to be selected by Scotland, taking his caps total to six.

“He also played once for the Scottish League in 1897 in a 3-0 victory over the English that ended with him being carried shoulder-high from the pitch.

“After nine years with Dundee, he returned to Montrose in 1902 and, despite being in his mid-30s, had several years of football left in him.

“But his other sport was golf and, as a member of Mercantile GC in the town, he won the links championships six times and lived in Montrose all his life until he died there, aged 92, in 1960.”

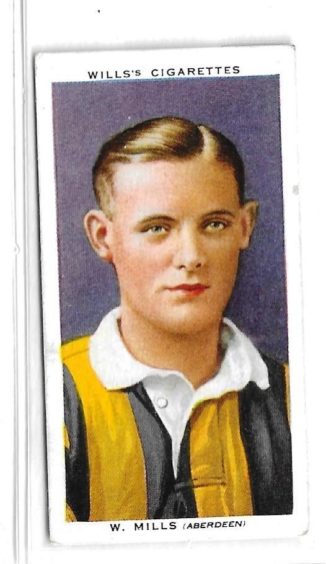

Mills didn’t bomb on the big stage

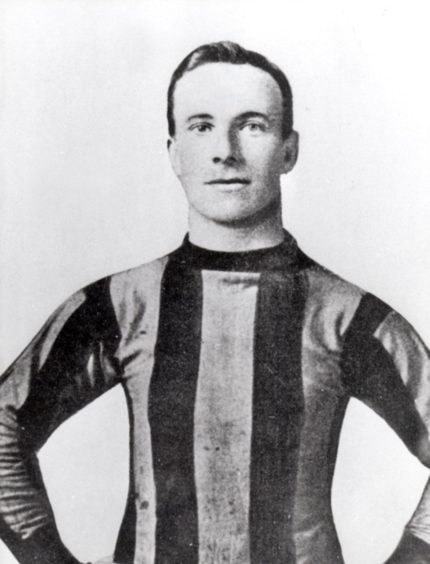

Overnight sensations don’t happen much swifter than the dramatic elevation of Willie Mills once he arrived in Aberdeen from the central belt in 1932.

After just a single match for the reserves, the 17-year-old was flung into the First XI and developed into one of the successful and consistent Dons of his generation until the war cast a cloud over so many in his mould.

Pittodrie aficionados marvelled at his creativity, penchant for a long pass and capacity to orchestrate controlled mayhem and score goals regularly.

The SFA’s observers were equally impressed and Mills toured the USA with Scotland in the summer of 1935 and was involved in the Jubilee international against England at Hampden [where the hosts prevailed 1-0] before winning three full caps for his country.

Mr Mitchell said: “The nearest he came to a major medal with Aberdeen was the Scottish Cup final of 1937, which was lost to Celtic and he moved to Huddersfield in March 1938 for a substantial fee of around £6,500.

“However, a year later, when war was declared, he returned to Scotland and joined the Infantry Training Centre in Perth, later serving with the British Army of the Rhine in Germany, and making guest appearances for a number of clubs around the country when he was available.”

The honours and plaudits kept coming. At one of his stops, he won the Forfarshire Cup with Dundee in 1945, then was appointed player-manager of Highland League sides Lossiemouth and Huntly.

Then, in 1950, he travelled to Malta to coach Hamrun Spartans and enjoyed warmer temperatures for a period prior to picking up the pieces again in the Highlands at Keith and Huntly.

After hanging up his boots, this redoubtable customer remained fit enough to appear in charity matches in the 1970s when he in his 50s.

And though he died in 1990, aged 75, he’s another of the players whose exploits are gradually being unearthed by a wider audience.

Mr Mitchell’s book testifies to the often entrepreneurial spirit and sense of adventure of these internationalists, who flourished in a febrile world.

But there were tragedies as well and scenes which echoed the sorrow felt by the football world when Denmark’s Christian Eriksen collapsed on the pitch during last weekend’s European Championship tussle with Finland.

Thankfully, the Inter Milan player is now recovering from his cardiac arrest. But there was no such happy outcome for a young prodigy from Fife who was involved in a dreadful incident on the pitch in 1931.

Young John was only 22 when he died

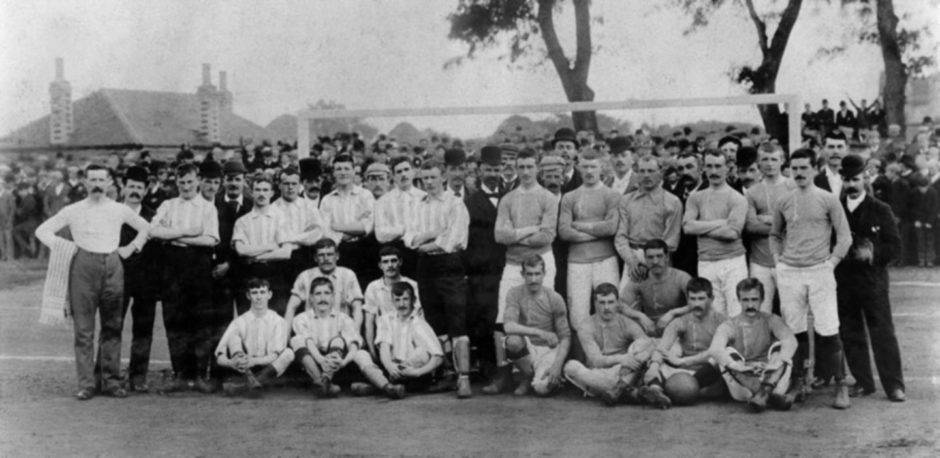

John Thomson, the “Laddie frae Cardenden” seemed destined to become one of his sport’s great figures.

Born in Kirkcaldy in 1909, he had gone down the pits while developing his skills in Fife junior football and earned a reputation as an outstanding goalkeeper even before he signed for Celtic in November 1926.

As Mr Mitchell said: “He was such a success that he played in every match to the end of the season, winning the Scottish Cup as an 18-year-old.

“He barely missed a game, with just a few weeks out through injury in the spring of 1930 and made his Scotland debut in Paris that summer, keeping a clean sheet and retaining his place for all three home internationals the following season, conceding just one goal.

Both clubs mourned his death

“In the summer of 1931, he enjoyed a six-week tour of America with Celtic, and looked set for another glorious season. But then came that fateful September afternoon at Ibrox.

“Early in the second half, he dived bravely at the feet of Rangers forward, Sam English, whose knee crashed into Thomson’s head. He was carried off the field and rushed to the Victoria Infirmary, but died five hours later of a depressed fracture of the skull.

“His death shocked the nation and his funeral procession in Cardenden was attended by tens of thousands of mourners.”

Thomson’s fate was mercifully rare, but this new book doesn’t shrink from reminding us of the human cost of the beautiful game.

And even today, 90 years later, it’s obvious that most fans know the difference between a missed penalty or fluffed shot and a genuine tragedy.

The Men who Made Scotland (1872-1939) is available on Amazon.