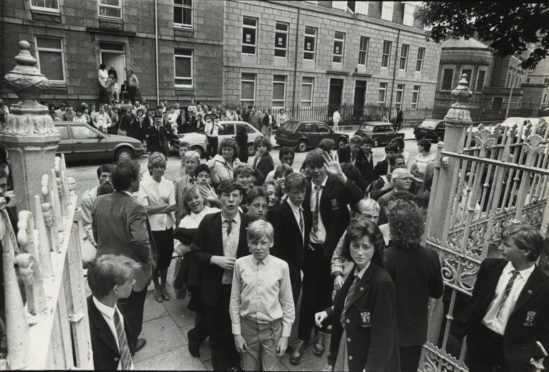

Stunned pupils and teachers could only look on 35 years ago as a ferocious blaze quickly reduced Aberdeen Grammar School to a charred shell.

What started as routine joinery work on the building sparked a catastrophe.

Within hours, the ancient seat of learning lost dozens of priceless and irreplaceable documents and artefacts – including a textbook used by Lord Byron – but thankfully there was no loss of life.

Just minutes before the disaster unfolded around 11.05am, classrooms on the first and second floors were packed with young scholars.

But the majority of the 1300 pupils were outside or on the ground floor for mid-morning break as the flames crept silently through the vast roof space above.

The alarm was raised by 13-year-old student Steven Wood who spotted smoke on a first-floor corridor and hit the fire alarm before leaving the building.

Prefects ushered pupils outside, but there was no panic as most assumed it was a fire drill.

But this was no drill, and July 2 will long be remembered as a dark chapter in Aberdeen Grammar’s illustrious history.

Fire fought on three fronts

In the short time it took for Grampian Fire Brigade to arrive, the blaze was established and it was immediately obvious back up was needed.

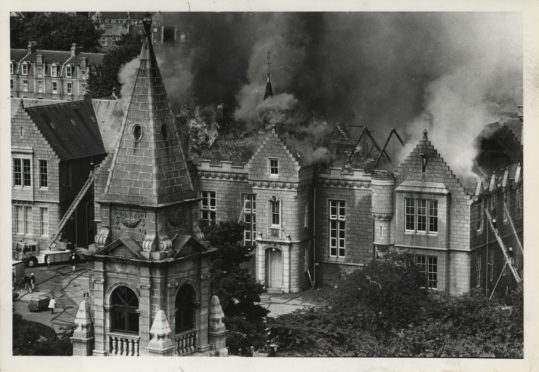

Masonry from the 120-year-old building, the older part of the school, crumbled and tumbled to the ground.

Windows exploded into shards over firefighters who were repeatedly beaten back by the inferno which engulfed the Grammar.

And the palls of thick, black smoke that hung ominously over the historic building could be seen for miles around.

Around 100 firemen, many of whom had been off-duty, were urgently called to the scene.

Men rushed in from stations in Banchory, Inverurie, Oldmeldrum and Stonehaven.

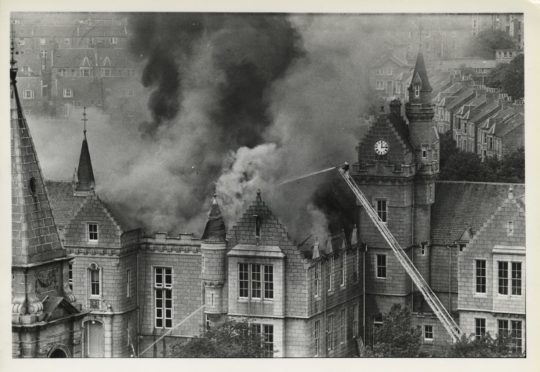

The colossal response saw 13 appliances, two turntable ladders, a hydraulic platform and other back-up equipment descend on the Grammar School.

Extra breathing apparatus was brought in and two off-duty control room women staffed a vital communications link on scene.

Every unit in Aberdeen was at the Grammar, and retained depots in Aberdeenshire were brought into cover the rest of the city.

A specialist turntable ladder was brought up from Tayside.

They fought the fire on three fronts – from the outside, and with two crews working on a pincer movement internally.

Firefighters fled as debris fell

But still it took hours to bring the flaming frenzy under control.

The dramatic destruction seemed to go on and on and on – the Victorian roof timbers were like a tinderbox.

Firemaster Neil Morrison led the complex operation, but there was little time for planning; it was unknown how far the blaze had travelled along the roof space.

Speaking at the time, he said: “We had men up 100ft ladders pouring water down from above.

“There were men on the roof – and fire fighting teams entering from either end of the building on the ground and first floors.

“The aim was to attack the fire where it was most obvious and try to confine and force it back – so we set up a line of defence.

“What made it more difficult was breaking into the roof, because the roof had a double skin – two layers of wood with a space between which allows hidden fire to travel.

“There was always the possibility the fire was travelling behind the men and cutting off their line of retreat.”

At one point, a man ran for his life as debris crashed down from the window he was firefighting.

Another two had their hands cut by falling splinters of glass and a third was struck on the back by falling wreckage.

The flames kept forcing the brave firefighters back to safety.

Mr Morrison added: “The spread of the fire was such that we had to withdraw our lines of defence as the fire came over the top of the men’s heads.”

But eventually, by 2.08pm, after a courageous battle, the rampant flames were brought under control – although the fire still raged.

Firemen worked well into the night to quell pockets of flames and dampen down the charred remains of buildings.

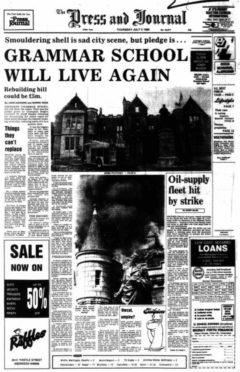

‘Saddest day in our history’

The cold light of the following day revealed the true extent of the destruction.

It was estimated that 90% of the roof has been destroyed, along with 70% of both the ground and first floors.

Beautiful towers had turned to cinders, and the precious library was lost – irreplaceable antiques went up in smoke.

Most of the mementoes of the Grammar’s eight centuries of history were housed in the historic library; items including a valuable Malayan clock had been turned to ash.

A physiology textbook used by former pupil Lord Byron, portraits of former rectors and heads of houses, trophies and a 16th Century edition of Erasmus’ ‘In Omnia’ – an item the British Museum didn’t even have – had all perished.

Fortunately, a school register which recorded the name George Gordon (Byron) had survived as it was in rector Robert Gill’s room.

His office was in the main administration block which was the only part of the main building to survive the blaze.

But the English department, most of history, geography and the art department weren’t spared.

Several main classrooms, a newly-equipped computing room and the staff common room were also completely destroyed.

Mr Gill said: “This is the saddest day in our long and distinguished history.

“It is a catastrophe for the school.

“The fire does not mean the end of the school.

“We will bounce back from this fire and the school will continue, but in what circumstances I cannot say at the moment.”

It was not the final year before retirement that Mr Gill had imagined.

Spirit lives on

Assessing the firefighters’ response, Mr Morrison said: “The fact that a number of wings are unaffected can be attributed to their efforts.

“The appliances and equipment we have can’t be bettered in any brigade in the UK.”

About £3 million of damage was estimated to have been caused with a predicted £5m rebuilding cost.

The school had only just recovered from the costs of a previous, deliberate fire, which seriously damaged the science block in February 1986.

This time, the cause was not malicious, but a careless and unfortunate error.

An electric heat gun was used by a 17-year-old apprentice from city firm Barscot to strip paint from a window.

But unbeknownst to him, the roof had been recently been sprayed with a preservative fluid, the vapours from which ignited.

Despite the tragedy, the pupils’ annual prizegiving went ahead the following week.

And after the holidays, the students’ education continued with minimal disruption in temporary classrooms affectionately known as “the village”.

In December 1986, ahead of his retirement in January, Mr Gill said although the fire was the worst event in his 14 years at the school, there was a glow of satisfaction at the “phoenix-like recovery”.

He added: “The spirit of staff and pupils this term has been quite remarkable.”

See more like this: